In the Newtonian sense of "giants on whose shoulders [s]he could look so far", knowledge generation in science is best characterised by a cumulative process that heavily relies and benefits from the existing work of other researchers (Moser and Biasi 2018, Nagler et al. 2019). Indeed, the emergence of the internet and the use of new digital technologies have fundamentally changed the way academics collaborate, communicate, and publish research (Pham et al. 2019, Schmitz et al. 2022).

Previously in the academic publishing market, it was common practice for publicly funded scientists to produce most of the journal content and for academic peers to contribute to reviews on a voluntary basis, next to what academic publishers invested in operating production and repository systems. However, technological changes in markets have incentivised some academic publishers to engage in price discrimination (Edlin and Rubinfeld 2005). As a result, the rise in subscription prices in the publishing market has led to a so-called ‘serials crisis’ (Ramello 2010, Eger and Scheufen 2018). In some cases, university libraries have reduced their holdings of academic journals in response to higher fees. Against this background, there is a broader public debate on how such markets can be organised in a more sustainable and efficient way.

Notably, the situation in the wake of the serials crisis is particular difficult for academic institutions located in developing countries that often lack the necessary resources. In the past, many local institutions were barely able to pay subscription fees for academic journals (Annan 2004). As a result, the political will to involve researchers from all nations and make access to science more affordable to them surfaced globally. In the early 2000s, the opportunities for free or low-cost access to scientific content at the international level were fully recognised which led to the development of the Research4Life (R4L) initiative.

Research4Life and the Hinari programme

The R4L initiative provides free or low-cost access to more than 200,000 journals and books for more than 11,500 academic institutions in 125 countries in the fields of health science (Hinari 2002), agriculture science (AGORA 2003), environmental science (OARE 2006), innovation (ARDI 2009) and research for global justice (GOALI 2018). Eligible are scientific institutions in countries, areas, or territories with a total gross national income (GNI) below $1 trillion, giving free access (Group A countries) to the complete collection to countries with a GNI at or less than $500 billion or reduced-fee access (Group B countries) to other eligible countries. Access to journals and book collections by individual scientists in the respective areas (Hinari, AGORA, OARE, ARDI, and GOALI) depends on the registration of the scientific institutions.

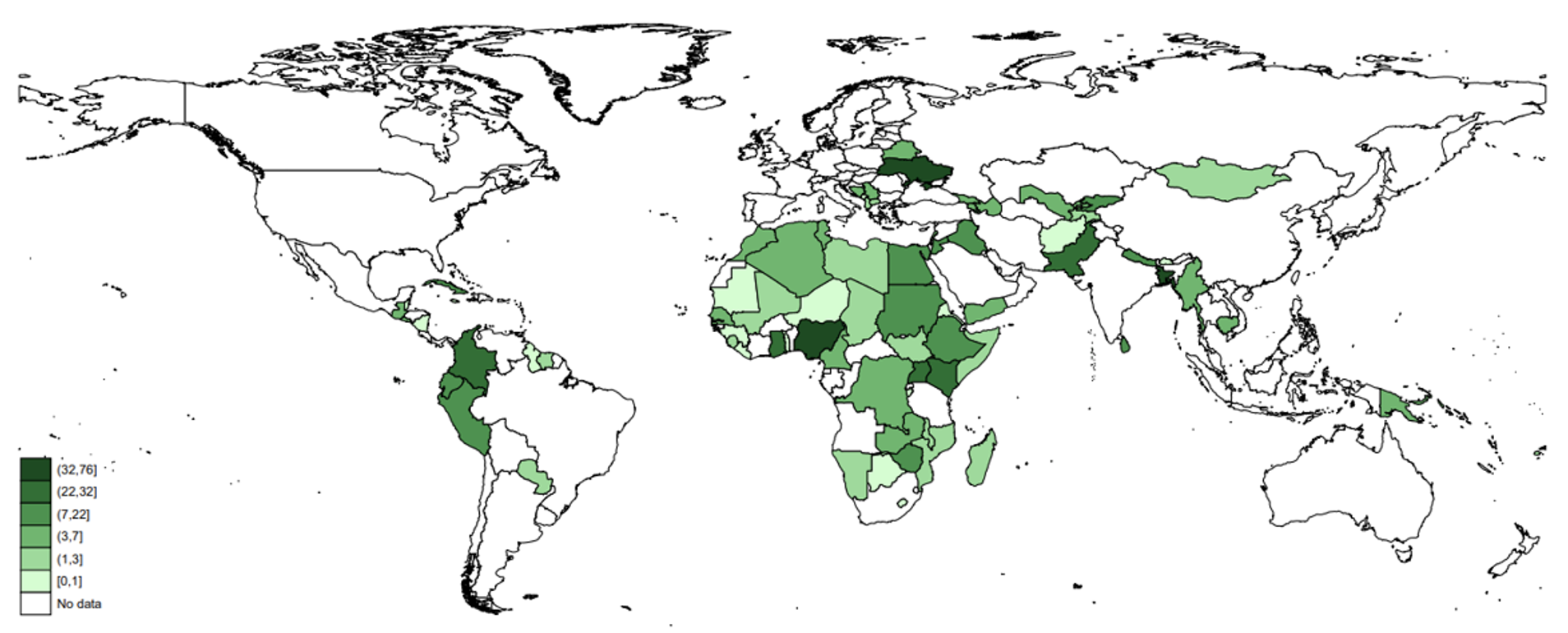

Using registration data from the WHO and finding more than 167,000 papers co-authored by local researchers in developing countries by screening 36 million papers available in the PubMed-repository, in our recent paper (Cuntz et al. 2024) we focus in particular on the health science orientated Hinari-programme. Figure 1 shows the geo distribution by percentiles (0-25%, 25%-50%, 50%-75%, 75%-90%, 90%-95% and 95%-99%) for Hinari-field publishing institutions. Against this background, the Hinari-field institutions in Nigeria, Ukraine and, Bangladesh are among the most productive in the Hinari sector.

Figure 1 Hinari institutions by country

Results: Scientific output, clinical trials

Our study examines the impact of free or cost-reduced online access for research institutions in developing countries. It raises two main questions:

- How does Hinari programme registration and improved informational access to health sciences affect the publication output by institutions and researchers in developing countries?

- To what extent does this free or low-cost access to scientific information trickle down or encourage further clinical trial research and innovation in health or pharmaceutical related fields?

With reference to research question (1), we find a substantial increase in scientific output of up to 75% following registration to the Hinari programme. For example, an institution with an average of 100 publications per year can increase this output to up to 175 publications on average, almost doubling the number of publications after joining the programme. Concerning clinical trials in research question (2), we find an average increase in participation in international clinical trials of up to 20% as a result of Hinari registration. These results show particular potential for the research and development of pharmaceutical products to combat rare diseases (Fischer et al. 2022) – i.e. problem solving for local diseases for which the financial incentives to develop appropriate drugs are often lacking in developing economies (Kremer 2002, Mueller-Langer 2013). Both results make it clear that free or reduced-cost access to scientific content promotes scientific output and potential innovations in the pharmaceutical and health sectors – a clear and positive message to the initiators of the Research4Life initiative to continue their efforts and move step by step closer to the goal of involving all nations in science.

From a methodological perspective, higher-performing institutions might be better informed and more likely to participate in the programme in the first place. Arguably, this could upward bias study results. Hence, we also compare institutions treated under the programme to those not participating in the programme, as well as look at differences in output performance among various research fields within the same institution, bearing in mind that HINARI is discipline-specific and covers only health-related information. This difference-in-difference-in-differences approach builds on work by Mueller-Langer et al. (2020). It therefore addresses potential endogeneity concerns from institutional selection into the programme.

Outlook: Innovation

In addition to the changes observed for scientific output and clinical trials, we also look at the impact on innovation more broadly by examining the impact of the Hinari programme on the patenting of inventions in health and related sciences. In theory, there could be knowledge and technology spillovers from the basic research conducted at local institutions to industrial research applications and the development of innovations. However, local spillover effects are expected to be minor under the programme, meaning that only a few patents will result from programme-induced research collaborations between industry and science. This does not allow for a well-founded empirical analysis of the output. Against this background, we develop an alternative approach by analysing Hinari-related scientific publications as cited in patents. However, the positive effect of the Hinari programme is not confirmed from this input perspective. At the same time, results point to new research opportunities that question the architecture of the innovation process and collaboration between industry and science (Meier et al. 2022).

References

Annan (2004), “Science for all nations”, Science 303: 925.

Cuntz, A, F Mueller-Langer, A Muscarnera, P C Oguguo, M Scheufen (2024), “Access to science and innovation in the developing world”, WIPO Economic Research Working Paper No. 78, Geneva: World Intellectual Property Organization.

Edlin, A S, D L Rubinfeld (2005), “The bundling of academic journals”, American Economic Review 95(2): 441-445.

Eger, T, M Scheufen (2018), The economics of open access: On the future of academic publishing, Edward Elgar Publishing.

European Commission (2012), “Commission Recommendation of 17 July 2012 on access to and prevention of scientific information”.

Fischer, A, M Goldman and M Dewatripont (2022), “Improving the innovation/access trade-off for rare diseases in the EU after Covid-19”, VoxEU.org, 29 September.

Kremer, M (2002), “Pharmaceuticals and the developing world”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 16(4): 67-90.

Meier, J-M, R Silva and A Donges (2022), “The impact of institutions on innovation” VoxEU.org, 20 May.

Mueller-Langer, F (2013), “Neglected infectious diseases: Are push and pull incentive mechanisms suitable for promoting drug development research?”, Health Economics, Policy and Law 8(2): 185-208.

Mueller-Langer, F, M Scheufen and P Waelbroeck (2020), “Does online access promote research in developing countries? Empirical evidence from article-level data”, Research Policy 49(29): 1-22.

Moser, P, B Biasi (2018), “Effects of copyrights on science”, VoxEU.org, 26 May.

Nagler M, M Watzinger and J L Furman (2019), “Disclosure and subsequent innovation: Evidence from the Patent Depository Library programme”, VoxEU.org, 31 March.

Pham, T, O Talavera and Y Gorodnichenko (2019), “Conference presentations and academic publishing”, VoxEU.org, 21 December.

Ramello, G B (2010), “Copyright and endogenous market structure: A glimpse from the journal-publishing market”, Review of Economic Research on Copyright Issues 7(1): 7-29.

Schmitz, M, S Heblich, F Monte and W Walker Hanion (2022), “Communication costs, science, and innovation”, VoxEU.org, 15 July.