The visual arts market, in general, and the prices commanded by paintings at the two leading auction houses, in particular, tend to peak at the end of economic expansions, so the various records broken so far in 2008 may spell mixed news. The arts market remains of interest to economists, though, as it an empirical testing ground for auction theory, in which interest has grown significantly in recent years (Klemperer 2004). Despite extensive scholarly and media interest, there are a number of aspects of the workings of the arts market that are still not well understood, including four puzzles. What determines the auction price of a painting? Why is that only two-thirds of all lots (paintings) sell at auction? Are masterpieces good investments? Do prices systematically decline during an auction (that is, is there an “afternoon effect”)? In recent research, Renata Leite Barbosa and I revisit these four puzzles using a unique data set produced by coding by hand the full pre-action catalogue of Sotheby’s Latin American Art November auctions between 1995 and 2002 (Campos and Leite 2008).

Pay and display: What determines the price of a painting?

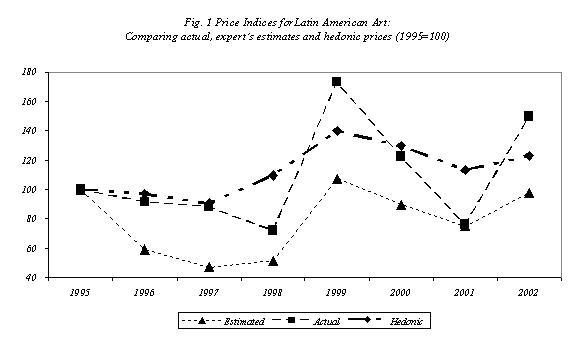

Many art dealers insist that it is impossible to decompose or explain the price of a painting. Economists, however, disagree and over the years have provided robust answers to this question. The extensive econometric evidence from art auctions suggests that factors such as medium and size are main determinants of the price of artwork (Burton and Jacobsen 1999). However, these findings are generated from commercial electronic databases on the arts market, databases that include only a fraction of the information available to potential buyers (indeed, even a fraction of the information in pre-auction catalogue.) Would these factors still play such a dominant role if factors not normally considered in this literature (such as the provenance of the artwork, participation in major exhibitions and emphasis in the arts literature) were taken into account? Our results show that artist’s reputation and the work’s provenance turn out to be significantly more important price determinants than more commonly studied factors such as size, theme and medium. Moreover, taking these oft-neglected factors into account improves the precision of estimates for art returns. Figure 1 shows three price indexes. The first is based simply on the “actual” average price, per auction. The second index, labelled “estimated,” is an index based on art expert’s price estimates (price estimates produced by Sotheby’s Latin American Art Department published in the pre-auction catalogue). The behaviour of the two indices over auctions (over time) is similar, especially after 1997. The third index shown is the hedonic price index, which incorporates the new reputation and provenance variables mentioned above. In line with other results in the literature (e.g., Buelens and Ginsburgh 1993), the hedonic index exhibits much less variability. Further, returns based on this index tend to be larger than those based on any of the other two indexes. Finally, note that the hedonic index underestimates actual auction prices at various points, which is consistent with the notion that “better” paintings tend to come to the market during “booms.”

Why do some paintings fail to sell?

A common feature of art auctions is that not all lots are actually sold. “Bought-in” paintings, using auction houses’ terminology, fail to command a price above the reserve price that is set jointly by the seller and the auction house (on average, a third of the lots are “bought-in”). Recent studies have uncovered an important role for art experts in this process. There are at least two approaches to assess the role of experts: the first is suggested by Ashenfelter, Graddy, and Stevens (2002) and is based on the predictive power of the range of pre-auction price estimates produced by the auction house specialised department (Sotheby’s Latin American Art Department in this case). The second is developed by Ekelund, Ressler, and Watson (1998) and uses a number of variations such the mid-point of the range of pre-auction estimates, the gap between the latter and the actual price, and an estimate window. Our results show that predicting whether a painting sells is indeed a very difficult task. None of the long list of variables turns out to be statistically significant and, contrary to previous research (Ekelund et al. 1998), experts’ opinion is also of rather limited power in predicting the sale of artwork.

Are masterpieces good investments?

Many art auctions analysts believe in the existence of a “masterpiece effect,” namely, that the most expensive pieces of each artist command above normal returns. Pesando (1993) uses data on prints auctions to put forward evidence suggesting otherwise, that is, that masterpieces actually tend to under-perform the market (see also Ashenfelter et al. 2002, Mei and Moses 2002.) Like the correlation between price and the size of the painting, this is another issue on which economists disagree with those in the arts trade and have put forward empirical findings that suggest that the masterpiece effect does not hold. It is thus important to assess whether the effect is also absent in Latin American data. We estimate that the annual return to a “masterpiece” between 1995 and 2002 was -1.92%, while the same figure for the “non-masterpieces” was 5.63%. The rejection of the masterpiece effect holds for a range of ways of identifying a masterpiece, including whether or not the painting has been reproduced in an important art history book and whether or not it participated in influential art exhibitions.

Is there an afternoon effect?

One resilient puzzle identified in the literature is the “declining price anomaly.” This effect was identified by Ashenfelter (1989) and is an obvious repudiation of the law of one price. It refers to the observation that as an auction proceeds, the prices of the lots decline, even for identical goods (e.g., wines). Beggs and Graddy (1997) established the existence of the “declining price anomaly” for heterogeneous goods using data for Contemporary and Impressionist art auctions. This has generated great interest and a number of papers now report somewhat conflicting results in this respect, although the majority still seems to find evidence in favor of this anomaly (see Ashenfelter and Graddy 2003, and Ginsburgh and van Ours 2007.) In light of this controversy, it is of interest to investigate whether or not Latin American art auctions are also subject to the declining price anomaly or the so-called “afternoon effect” (“morning after effect” would be a more appropriate name in this context as Latin Art auctions occur in two parts, the first starting late in the day, say 7pm, and the second starting earlier the following day, usually 10am.) In line with previous research (Beggs and Graddy 1997), we find strong evidence that the “declining price anomaly” holds for Latin Art data, even after controlling for auction and artist unobserved characteristics (dummies) and a huge array of paintings characteristics, including reputation and provenance.

Concluding remarks

Our new results on the workings of the arts market show that artist’s reputation and artwork’s provenance seem to be more important determinants of the sale price of a painting than traditionally considered factors such as medium and size. Further, and contrary to previous research, experts’ opinion seem to have rather limited power in predicting the sale of artwork in auctions. In line with previous research, the notion that “masterpieces” command above normal returns also does not seem to hold for Latin American paintings. Finally, one of the central puzzles in the auction literature identified using art auctions data is the “declining price anomaly.” This refers to identical lots commanding different prices depending on where along the auction they are placed, with lots placed earlier in the auction receiving higher bids and consequently selling for higher prices. This new study provides further corroboratory evidence for this anomaly.

References

Ashenfelter, O. (1989) How auctions work for wine and art, Journal of Economic Perspectives 3, 23-36.

Ashenfelter, O. and Graddy, K. (2003) Auctions and the price of art, Journal of Economic Literature 41, 763-87.

Ashenfelter, O., Graddy, K. and Stevens, M. (2002). A Study of Sale Rates and Prices in Impressionist and Contemporary Art Auctions. Univeristy of Oxford mimeograph.

Beggs, A. and Graddy, K. (1997) Declining values and the afternoon effect: Evidence from art auctions, Rand Journal of Economics 23, 544-65.

Buelens, N. and Ginsburgh, V. (1993) Revisiting Baumol’s art investment as floating crap game, European Economic Review 37, 1351-71.

Burton, B. and Jacobsen, J. (1999) Measuring returns on investments in collectibles, Journal of Economic Perspectives 13, 193-212.

Campos, N. and Leite, R. (2008), Paintings and numbers: An econometric investigation of sales rates, prices and returns in Latin American art auctions, CEPR DP6806, April.

Ekelund, R., Ressler, R. and Watson, J. (1998) Estimates, bias and ‘No Sales’ in Latin American art auctions, 1977-1996, Journal of Cultural Economics 22, 33-42.

Ginsburgh, V. and van Ours, J. (2007) How to organize sequential auctions: Results of a natural experiment by Christie’s, Oxford Economic Papers 59, 1-15.

Klemperer, P. (2004). Auctions: Theory and Practice. Princeton University Press.

Mei, J. and Moses, M. (2002) Art as an investment and the underperformance of masterpieces, American Economic Review 92, 1656-68.

Pesando, J. (1993) Art as an investment: The market for Modern prints, American Economic Review 83, 1075-89.