The European Commission (2012) has presented its legislative proposal for banking union whose key element is a ‘Single Supervisory Mechanism’ to be headed by the ECB, but leaves resolution and deposit insurance at the national level. Is that viable? A recent paper by Pisani-Ferry and Wolff (2012) on the fiscal implications of a banking union argues that a common deposit insurance fund is not necessary at this point. The reason given is that deposit funds insure against the failure of a single, small financial institution, but not against the failure of the Eurozone financial system. They consider deposit insurance therefore as a second order issue. By contrast, in recent work with Daniel Gros (Gros and Schoenmaker 2012), I argue that depositor confidence can be strengthened immediately by a gradual phasing in of a credible European deposit insurance fund. Carmassi et al (2012) also argue for an integrated approach for the three functions of banking supervision, deposit insurance and resolution. Finally, Van Rompuy (Van Rompuy Report 2012) has presented his report Towards a Genuine Economic and Monetary Union with four building blocks. Building on the Single Rule Book, the first building block on an integrated financial framework includes European banking supervision, a European Deposit Insurance Scheme and a European Resolution Scheme.

This paper first explains why an integrated architecture for the proposed banking union is needed. The key element is to get the incentives right. Next, I argue for combining deposit insurance and resolution on efficiency grounds. The argument is that we need a few strong institutions at the European level instead of multiple agencies with partly overlapping mandates and information needs.

Architecture of a banking union

Economists use a ‘backwards’ approach when looking at the link between supervision and deposit insurance and resolution. The endgame of resolution and deposit insurance drives the incentives for ex ante supervision (Schoenmaker, forthcoming).

In the current setup, the EC is the rule maker and the ECB the lender of last resort for the European banking system. The EC is the key policymaker, initiating new policies and rules for the financial system. In parallel, the European Banking Authority (EBA) has a key role in drafting technical standards and developing a single rulebook for the EU internal market.

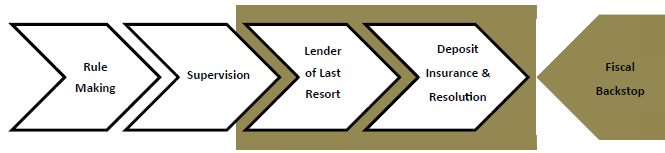

The new proposals for a banking union envisage a supervisory role for the ECB. In this article, I argue that there is also a need for a European Deposit Insurance and Resolution Authority (EDIRA). The final stage in the governance framework is the fiscal backstop. Crises affecting banks are commonly macroeconomic and general in nature, following asset market collapses and economic downturns. The existing national deposit insurance and resolution funds can thus quickly run out of funds (Spain, Ireland) and need the ultimate backup of government support. But a widespread asset market collapse coupled with an economic downturn can push even the sovereign into insolvency, as the cases of Ireland and Spain have shown. Then either the sovereign itself will need a backstop, or the backstop will have to come from a different source. The European Stability Mechanism (ESM) was created to provide the fiscal backstop for member countries, and possibly also the banking systems of member countries in financial distress. The stability of a banking system can be assured only if investors know that such a backstop exists. The arrow for the fiscal backstop is thus backwards in Figure 1, illustrating our backwards-solving approach towards governance. (See Schoenmaker, forthcoming, for a full analysis of a governance framework for international banking.)

Figure 1. European institutions for financial supervision and stability in a banking union

Note: The framework illustrates the five stages from rule making to the fiscal backstop. The bottom line shows the agency for each function.

Source: Schoenmaker (forthcoming)

A system under which the deposit insurance and resolution functions remain national while the supervision and lender of last resort functions move to the ECB would lead to serious problems. Dewatripont and Tirole (1994) stress the point that as depositors are guaranteed, they will no longer have an incentive to monitor the bank. Normally the supervisor then takes over the monitoring role representing the depositors. This is naturally the case at national level, where both the supervisor and the deposit insurance system are part of the same government. But this would not be the case for Europe if only supervision were centralised and national authorities remained responsible for deposit insurance and restructuring. The ECB would have an incentive to offload the fiscal cost of any problem to the national authorities.

As long as deposit insurance and resolution remained at the national level, serious conflicts would arise if the ECB thinks that any given bank needs to be restructured or closed down. The ECB would do this on the basis of its assessment of the viability of the bank and any danger it might represent to systemic stability at the Eurozone level. By contrast the national deposit insurance systems and, more generally, the national authority responsible for bank restructuring (i.e. in practice today’s supervisors and finance ministries) would have a tendency to minimise their own costs by keeping the bank alive through support from the ECB. National authorities would naturally have a tendency to blame an ‘unfair’ ECB for not recognising the strength of ‘their’ bank which should not be closed, but saved. This type of conflict is likely to be especially prevalent at the start of the new system when the ECB has to discover all the ‘skeletons in the closet’ hidden thus far by national supervisors.

Over time other conflicts will arise; for example if the ECB has made a mistake and led a bank to take too much risk. National authorities would then have a point in complaining if they had to pay up for the cost of this mistake. The best way to avoid these potential conflicts and provide the new Eurozone supervisor with proper incentives is to move gradually deposit insurance and resolution to the Eurozone level as well, thus ensuring eventually the needed alignment of responsibilities. A gradual introduction would ensure that during the transition both national and EU level authorities have ‘a skin in the game’. (See Schoenmaker and Gros 2012 on how to gradually introduce an EDIRA.)

In sum, a system of European supervision and national resolution is not ‘incentive compatible’. A European underpinning of deposit insurance and resolution is an indispensable complement to moving supervision to the ECB.

Combine deposit insurance and resolution

Figure 1 depicts the bodies in the new European governance framework. While the EC, the ECB, and the ESM are existing institutions; the EDIRA would be a new institution. Although it is tempting to place the new resolution authority at the ECB, the functions of supervision and resolution should remain separate (ASC 2012). As supervisors have responsibility for the licensing and ongoing supervision of banks, they may be slow to recognise (and admit to) problems at these banks. Supervisors may fear that inducing liquidation before a bank becomes insolvent could, in some cases, cause panic in the market. A separate resolution authority can judge the situation with a fresh pair of eyes and take appropriate action with much needed detachment. The private banking sector also applies this principle of separation. When a bank loan becomes doubtful, responsibility is transferred from the loan officer to the department for ‘special’ credits to foster a ‘tough’ approach. Given the need for a fiscal backstop, the new EDIRA could operate in close cooperation with the ESM. It is nevertheless important to guard the independence of the resolution authority, as the ministries of finance govern the ESM.

Deposit insurance and resolution are in principle separate functions. In the US they have been combined. The Dodd-Frank Act assigns resolution powers for large banks to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), in addition to the existing FDIC powers for smaller banks. Similarly, the Deposit Insurance Corporation of Japan has resolution powers. By analogy, Allen et al (2011) suggest combining the two functions within some kind of European equivalent of the FDIC. The EU would then also get a deposit insurance fund with resolution powers. The combination allows for swift decision making. Moreover, the least cost principle (choosing between liquidation with deposit payoffs or public support) can then internally be applied in each case. That would also contribute to swift crisis management.

The EDIRA would be fed through regular risk-based deposit insurance premiums from the banks whose customers benefit from its protection, i.e. the European banks supervised by the ECB. Any new deposit insurance scheme has to face the problem of the transition to the new steady state (see Schoenmaker and Gros 2012). The establishment of a viable fund is important. A suggestion is to start off with a European deposit insurance fund funded by deposit insurance premiums. Once the fund is beyond a certain size, it can also be used for resolution turning it into a fully-fledged European deposit insurance and resolution fund. In that way, private-sector funds are available for resolution in crisis management. To ensure that sufficient private funds are built up, the cap on the size of the fund should not be too small (as is currently the case with some deposit insurance funds).

National deposit insurance funds have an implicit or explicit fiscal backstop of the national government. With the ESM up and running a fiscal backstop can be easily implemented for a Eurozone-based EDIRA. All one would need for an EU-wide system would be a burden sharing mechanism between the ESM and the other member countries (Goodhart and Schoenmaker 2009). In the case of the rescue package for Ireland in 2010, the euro-outs (UK, Denmark, and Sweden) joined in the burden sharing following the ECB capital key, as UK banks were exposed to Ireland and would therefore also benefit from enhanced financial stability in Ireland. That shows that burden sharing can be widened if needed.

Conclusion

The debate about banking union is running into the typical ‘chicken and egg’ problem: Most academic observers agree that deposit guarantee and resolution should be organised at the same level as supervision. But at present only the creation of a ‘Single Supervisory Mechanism’ (SSM) to be headed by the ECB is being discussed; with deposit insurance and resolution to be considered only later when this SSM has shown its effectiveness. I argue that the SSM is unlikely to work well unless an EDIRA is introduced gradually at the same time.

References

Advisory Scientific Committee (2012), “Forbearance, Resolution and Deposit Insurance”, Reports of the Advisory Scientific Committee, 1.

Allen, F, T Beck, E Carletti, P Lane, D Schoenmaker, and W Wagner (2011), “Cross-Border Banking in Europe: Implications for Financial Stability and Macroeconomic Policies”, CEPR Report, London.

Carmassi, J, C Di Noia, and S Micossi (2012), “Banking Union: A federal model for the European Union with prompt corrective action”, CEPS Policy Brief, 282.

Dewatripont, M and J Tirole (1994), Prudential Regulation of Banks, Cambridge, Mass, MIT Press.

European Commission (2012), “A Roadmap towards a Banking Union”, COM(2012) 510 final, Brussels.

Goodhart, C and D Schoenmaker (2009), “Fiscal Burden Sharing in Cross-Border Banking Crises”, International Journal of Central Banking, 5:141-165.

Gros, D and D Schoenmaker (2012), “The Case for Euro Deposit Insurance”, Duisenberg School of Finance Policy Brief, 19.

Pisani-Ferry, J and G Wolff (2012), “The Fiscal Implications of a Banking Union”, Bruegel Policy Brief Issue, September.

Schoenmaker, D (forthcoming), Governance of International Banking: The Financial Trilemma, Oxford University Press.

Schoenmaker, D and D Gros (2012), “A European Deposit Insurance and Resolution Fund: An Update”, Duisenberg School of Finance Policy Paper, 26 and CEPS Policy Brief, 283.