“[T]he real drama was not on Black Monday. The real drama was on Tuesday and several days thereafter when the fear of credit losses among major market participants threatened to produce market and credit gridlock, with all of its implications for market liquidity and further downward pressure on equity prices.” E. Gerald Corrigan, former President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 1998 (Corrigan 2010).

“'Will you open tomorrow?' he asked. That was the scariest moment because the truthful answer I gave was 'I do not know.' What the Fed Chair was really asking was: 'Will the longs pay the shorts?’"

Leo Melamed (1997), former CEO, Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME), recalling an October 19, 1987 late-night conversation with FRB Chair Alan Greenspan.

On Monday, 19 October 1987, the Dow Jones Industrial Average plunged 22.6%, nearly twice the next largest drop (the 12.8% Great Crash on 28 October 1929 that heralded the Great Depression).

What stands out is not the scale of the decline – it is far smaller than the 90% peak-to-trough drop of the early 1930s – but its extraordinary speed. A range of financial market and institutional dislocations accompanied the rapid plunge, threatening not just stocks and related instruments (domestically and globally), but also the US supply of credit and the payments system. As a result, Black Monday has been labelled “the first contemporary global financial crisis” (Bernhardt and Eckbald 1987). A new book, A First-Class Catastrophe, narrates the tense human drama that it created for market and government officials (Henriques 2017).

Our reading of history suggests that it was only with a great dose of serendipity that we were able to escape catastrophe in 1987. In this column, we review key aspects of the 1987 crash and discuss subsequent steps taken to improve the resilience of the financial system. We also highlight a key lingering vulnerability: we still have no mechanism for managing the insolvency of critical payment, clearing, and settlement (PCS) institutions.

What matters in a crash

We begin with three key points.

- First, no one can forecast the timing of the next crash.1

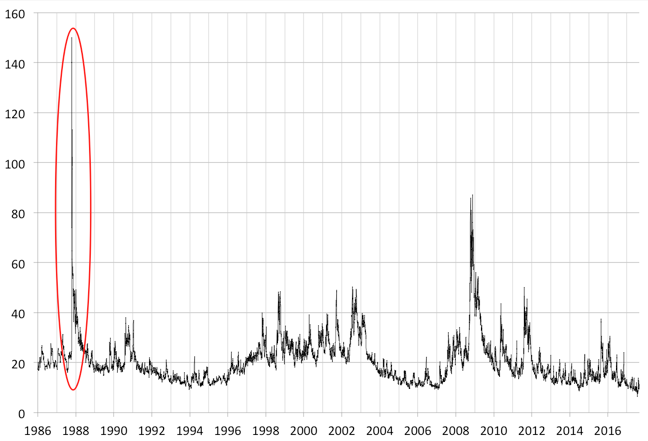

In October 1987, many well-informed observers (including Federal Reserve Board Chair Alan Greenspan) viewed the rise of the equity market that year as unwarranted by fundamentals. But, in retrospect, the degree of overvaluation does not seem large. For example, Shiller’s cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings (CAPE) ratio, one of our favourite indicators of fundamental value, was well below the levels of the mid-1960s. And, viewed from today’s vantage point, the CAPE ratio at the time was only 5% above the long-run mean (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Cyclically adjusted price-earnings ratio (monthly average), 1881 to September 2017

Note: Horizontal blue line denotes long-run mean. Red oval shows 1987 crash.

Source: Robert Shiller website.

- Second, from a macroeconomic perspective, the key concern arising from a plunge in US equities generally is not the resulting loss of wealth.

To see why we say this, note that the internet stock bust that started in 2000 led to an enormous $9 trillion peak-to-trough domestic loss of equity wealth (in an economy with a GDP of $10.3 trillion), yet the ensuing recession was the mildest in US postwar experience. Similarly, in the aftermath of Black Monday, where the loss of equity wealth was less than $1 trillion (with GDP of $4.9 trillion), the economy grew by 4% over the next year!

Instead, as we learned in the 2007-09 crisis, the key question is whether sudden changes in asset prices undermine critical functions of the financial system. In our minds, the two most prominent concerns are the performance of the payments system and the continued supply of credit to healthy borrowers. In this case, the vulnerability arose from the fact that critical leveraged intermediaries – especially broker-dealers and investment banks – were highly exposed to equity market fluctuations. In turn, banks were important lenders to these firms. Similarly, the PCS firms were exposed to the failure of their members, including those firms that traded actively in derivatives or in the equities on which they are based.

- Our third concern is confidence in the financial system itself.

The US equity market is arguably the crown jewel of American capitalism. A key function of any financial system is to channel private savings – the sum of business profits and the income that households don’t consume – into productive investment. When equity markets are working efficiently, prices aggregate information, signalling where investment opportunities are the most beneficial. The corollary also holds: a persistent loss of confidence in the equity markets – particularly in the price discovery process – reduces the mobilisation and effective allocation of savings.

1987: The threat to market function

A few examples from 1987 highlight our concerns about market function. Derivatives markets are a zero-sum game: for every long, there is a short. In the absence of bankruptcy, the net effect on wealth of any market movement, big or small, is zero. When price movements are large, it is not the net effect but the gross impact that matters. The reason is that, faced with big losses, some market participants may become insolvent. And, if the problem is large and widespread, this can lead to cascading failures.

The 19 October crash shifted wealth massively from longs to shorts, prompting a flood of margin calls and raising the longs’ demand for credit to meet these calls. For those unable to pay on time, clearing agents were contractually obligated to make the payments on their behalf, and bear the losses. Rumours about the solvency of some of the PCS entities probably diminished trading and – due to the presence of first-mover advantage – could have triggered a run by member firms who were still solvent.

A dramatic example of such disruption is the case of the largest options clearing firm at the time, First Options of Chicago, an affiliate of Continental Illinois. To avoid failure, on 19 and 20 October, the bank injected several hundred million dollars of capital into the clearing agent – against the explicit wishes of its federal supervisor, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (Flynn 1987). Keep in mind that, following Continental’s $4.5 billion bailout in 1984, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) owned 60% of the firm’s equity (US House of Representatives 1988: 1 and 3). Continental later reported more than $100 million in losses in the aftermath of the crash (Atlas 1988).

The morning of 20 October is a critical stage in this saga. As the initial quote from CME chief Leo Melamed highlights, even he did not know if the longs would be able to cover the estimated $2.5 billion transfer of wealth to the shorts in time to allow the Exchange, the home to equity futures trading, to open. In fact, they could not. To open, the Exchange borrowed $100 million – again from Continental Illinois (how fortunate to have a government-owned bank as your creditor in a crisis!) – to cover its contractual obligations (Melamed 1997). One can only speculate about the wave of disturbances that might have resulted had the CME failed to open that day.

The lender of last resort

In addition to the exchanges, broker-dealers needed funds to meet margin calls and to provide credit to their customers. A loss of funding liquidity on 20 October would surely have amplified and extended the fire sales of 19 October. This, in turn, could have led to problems similar to the ones that we saw in 2007. Lenders, including banks, would not have been able to distinguish sound from distressed counterparties, resulting in a disastrous credit freeze (Cecchetti and Schoenholtz 2017a).

Yet, instead of pulling back, banks increased lending to the securities firms, aiding a quick recovery (e.g. Bernanke 1990). Most observers credit the Federal Reserve’s response, in its role as lender of last resort, as the force behind banks’ willingness to lend to risky securities dealers. The Fed kicked off the day on Tuesday, 20 October, with a one-sentence statement: “The Federal Reserve, consistent with its responsibilities as the Nation's central bank, affirmed today its readiness to serve as a source of liquidity to support the economic and financial system” (Carlson 2007). In addition, they conducted open-market purchases at an earlier time than was normal, and in a manner that lowered the federal funds rate (interrupting the policy tightening aimed at reducing inflation). Finally, and perhaps most important, the Fed engaged in moral suasion: the New York Fed President Corrigan, whom we quote above, reportedly called big bank CEOs to impress upon them the “big picture, the well-being of the financial system” without instructing them to ignore solvency risk (Sterngold 1987, Henriques 2017: 240).

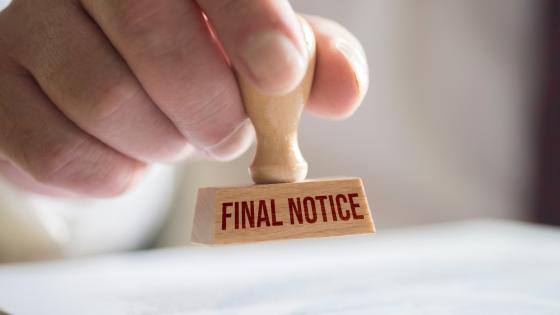

What about confidence in the function of the equity market? On 19 October, the price discovery process collapsed. Surging trading volume led to delays in transaction reporting, resulting in the execution of many orders at prices far from the stale ones posted. On 20 October, the intra-day price swings became enormous, with the S&P 500 futures opening up 17%, then plunging 25%, only to bounce back later in the day. The point is that, as Greenwald and Stein (1988) emphasise, because of the information they convey, market prices are like public goods. But, during and just after the crash, delayed reporting and executions, combined with record volatility (see Figure 2), undermined this value. Fortunately, in the absence of large intermediary failures, any loss of confidence proved temporary, and the system recovered.

Figure 2 CBOE S&P 100 Volatility Index (VXO), 1986 to September 2017

Note: Red oval highlights October 1987 episode.

Source: CBOE.

Reforms to promote resilience

Looking back, since 1987, there have been numerous reforms aimed at improving the resilience of the financial system. A list of some of the most important starts with the enormous increase in capacity for speedy trade execution. Next is the implementation of circuit breakers designed to limit disorderly trading and maintain the integrity of price discovery. Third is the effort to damp the surge in credit demand arising from price swings – for example, through cross-margin arrangements that limit margin calls for institutions with hedged positions across different PCS platforms.2 A fourth critical reform is the 2007-2009 crisis-driven restructuring of the largest, formerly independent, securities firms as components of better-capitalised and better-supervised financial holding companies. Finally, there is the advent of a financial regulatory framework – fashioned by the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 – that explicitly focuses on monitoring and mitigating systemic risk.

Among Dodd-Frank’s important innovations is the power it grants the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) to designate critical PCS firms as systemically important financial market utilities (FMUs). At this writing, the Council has designated eight firms as FMUs, including the CME, the Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation (DTCC) and the Options Clearing Corporation (OCC), all of which are key to the operation of the US equity market. As FMUs, each of these firms is now subject to Federal Reserve scrutiny (in addition to that of their own supervisor).

Clearinghouse resolution: A lingering vulnerability

Are the reforms of the last 30 years enough? Is the current financial market infrastructure sufficiently resilient to withstand the next, inevitable, crash? Dodd-Frank does give the Fed the authority to lend to solvent FMUs. But, it is difficult to envision circumstances where these critical organisations would be solvent, but illiquid, with sufficient high-quality collateral to borrow from the lender of last resort. Importantly, the Fed is not legally authorised to lend to an insolvent firm – however systemic. Were the Fed to act knowingly beyond its authority – even in a crisis – it would almost certainly sacrifice the policy independence that it cherishes and that has brought great benefit to the US economy (Cecchetti and Schoenholtz 2016).

Our conclusion: there is a gaping hole in the fabric of the financial system. As Tuckman (2017) highlights, neither the Dodd-Frank Act nor the CHOICE Act passed this year by the House addresses the need for a resolution plan for insolvent PCS firms designated as FMUs. Instead, by mandating the shift of most over-the-counter derivatives to central clearing, Dodd-Frank has increased the systemic threat arising from the failure of a derivatives clearinghouse. If, as market participants probably assume, the government will inevitably act to sustain an insolvent FMU, it would be good to codify such a resolution plan – effectively an instantaneous nationalisation – now, rather than wait for another Black Monday.3

Authors’ note: An earlier version of this column appeared on www.moneyandbanking.com.

References

Atlas, T (1988), “1st Options’ Loss was $112 Million,” Chicago Tribune, 3 February.

Bernhardt, D and M Eckbald (1987), “Stock Market Crash of 1987,” Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

Bernanke, B S (1990), “Clearing and Settlement during the Crash,” Journal of Financial Studies 3(1): 133-151.

Carlson, M A (2006), “A Brief History of the 1987 Stock Market Crash with a Discussion of the Federal Reserve Response,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series No 2007-13, Federal Reserve.

Cecchetti, S G and K L Schoenholtz (2016), “The Lender of Last Resort and the Lehman Bankruptcy,” www.moneyandbanking.com, 25 July 25.

Cecchetti, S G and K L Schoenholtz (2017a), “Adverse Selection: A Primer,” www.moneyandbanking.com, 14 August.

Cecchetti, S G and K L Schoenholtz (2017b), “Resolution Regimes for Central Clearing Parties,” www.moneyandbanking.com, 9 October.

Corrigan, E G (2010), “Remarks, Panel on the Stock Market Crash of 1987 with Nicholas Brady and Gerald Corrigan”, in R E Litan and A M Santomero (eds), Brookings-Wharton Papers on Financial Services 1998.

Greenwald, B and J Stein (1988), “The Task Force Report: The Reasoning Behind the Recommendations,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 2(3): 3-23.

Flynn, J M (1987), “Losses at Options Unit Hurt Continental Illinois,” New York Times, 27 October.

Henriques, D B (2017), A First-Class Catastrophe: The Road to Black Monday, the Worst Day in Wall Street History, New York: Macmillan.

Melamed, L (1997), Remarks at the Panel on the Stock Market Crash of 1987 with Nicholas Brady and Gerald Corrigan, Brookings-Wharton Papers on Financial Services First Annual Conference Washington, DC, 29 October.

Sterngold, J (1987), “Stock Plunge Leads to Look at Safety Net,” The New York Times, 14 December.

Tuckman, B (2017), “Don’t Forget the Plumbing,” in M P Richardson, K L Schoenholtz, B Tuckman, and L J White (eds), Regulating Wall Street: CHOICE Act vs. Dodd-Frank, New York: NYU Stern School of Business, pp. 109-127.

U.S. House of Representatives (1988), “Volatility in Global Securities Markets”, Subcommittee on Oversight of the Committee on Energy and Commerce, Hearing, Series No. 100-118, 3 February 3.

Endnotes

[1] See, for example, Greenwald and Stein (1988).

[2] See, for example, here.

[3] For a detailed discussion of the need for resolution regimes for FMUs, see Cecchetti and Schoenholtz (2017b).