Moving the global economy back to a path of balanced, self-sustaining growth remains a difficult and unfinished task (see for instance Prasad and Foda 2012). Three challenges stand out.

- The financial sector in many advanced economies is still fragile.

Many banks remain overleveraged, with uncertainty about the quality of their assets still high, as reflected in price-to-book ratios that languish well below one.

- Government debt in many advanced economies is unsustainably high.

It currently standing at more than 110% of GDP in advanced economies, up from around 75% before the onset of the crisis and well above the threshold of 85% beyond which growth is thought to suffer.

- Large debt burdens and structural imbalances weigh on households and firms.

The total debt of the advanced economies’ non-financial private sector (households and non-financial corporates) amounts to roughly 190% of GDP. In many economies, a leverage-driven real estate boom began by misallocating resources and culminated in an enormous overhang of debt.

Addressing the challenges

The measures needed to address these challenges are clear.

- Banks must recognise losses and recapitalise.

- Governments must put fiscal trajectories back on a sustainable path.

- And households and firms must deleverage.

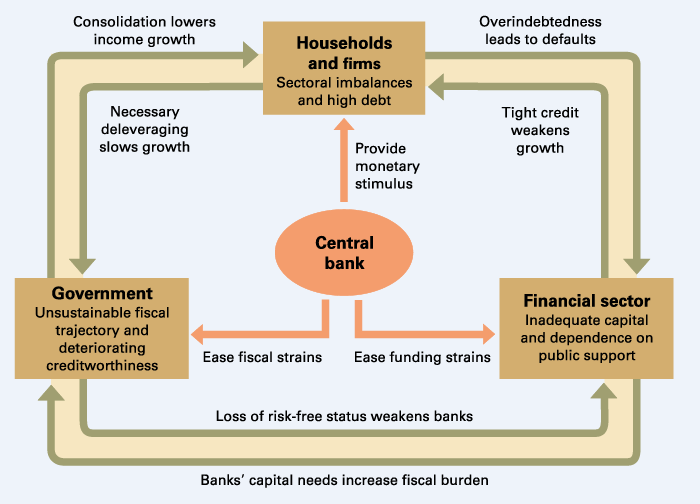

However, each sector’s burdens and adjustment efforts create adverse spillovers in other parts of the economy (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Breaking the vicious cycle

The financial sector’s capital needs add to fiscal burdens, while tight credit standards weaken growth, making deleveraging for households and firms more difficult. At the same time, the deteriorating creditworthiness of sovereigns weakens banks’ balance sheets by increasing the riskiness of their government bond holdings. For their part, fiscal consolidation efforts hamper growth, thus impeding private sector deleveraging. And as households and firms work to reduce their debt levels, they weaken growth in the short term and thereby erode bank balance sheets and government finances. The result of these interlinkages and spillovers is vicious cycles that lead to a prolongation of financial fragility and economic weakness.

Amid these cycles, the central banks of the core advanced economies are pushed to act as policymakers of last resort. They are providing monetary stimulus on a massive scale. They are supplying liquidity support to banks shut out of private markets. And they are easing government financing burdens by keeping interest rates low far out along the yield curve.

With policy rates at their effective lower bounds, the balance sheets of these central banks continue to expand with every new round of emergency lending to financial institutions and large-scale asset purchases. This extraordinary monetary accommodation feeds through to emerging market economies. This has given rise to an unusually loose stance of monetary policy globally. Global real interest rates are around zero, well below the trend growth rate of global output in recent years, while the world’s central bank balance sheets have bloated to unprecedented dimensions, now equating to around 30% of global GDP.

Decisive action by central banks to contain the crisis has played a crucial role in preventing a financial meltdown and in shoring up faltering economies. But there are limits to what monetary policy can do. It can provide liquidity, but it cannot solve underlying solvency problems. Prolonged and aggressive monetary accommodation has side effects that may delay the return to a self-sustaining recovery by reducing incentives to address balance sheet problems head-on. At the same time, it may create risks for financial and price stability, particularly in fast-growing emerging market economies. The gap between what central banks are expected to deliver and what they can actually deliver is growing, and it could – ultimately – undermine their credibility and independence.

Breaking the vicious cycles

It is therefore crucial that these vicious cycles be broken, and the pressure on central banks relieved. To achieve this, banks’ balance sheets must, as a first step, be cleaned up and strengthened. Banks must adjust their balance sheets to accurately reflect the value of assets and they must recapitalise. Progress has been made on this score, but the low level of bank price-to-book ratios – well below one – suggests that these efforts are still insufficient. Serious doubts about banks’ asset quality remain. To restore confidence in the banking sector, it is critical that policymakers put pressure on institutions to speed up the repair of their balance sheets as they implement Basel III universally and without delay.

Once banks have recognised losses on troubled assets and have recapitalised, their balance sheets will become stronger and more transparent. This will help banks regain access to private sources of unsecured funding, thus reducing asset encumbrance. In addition, it would foster sustainable economic growth by freeing up funding resources for new productive investment projects. Authorities must at the same time rein in the financial sector’s riskiness. To that end, there is a need to implement agreed financial reforms, extend them to shadow banking activities, and place curbs on the size and significance of the financial sector so that the failure of a single institution no longer sparks a sector-wide crisis.

In the Eurozone, the noxious effects of the vicious cycles have reached an advanced stage that reflects not only weaknesses seen elsewhere but also the incomplete state of financial integration within the currency union. Europe will overcome this crisis only if it can address both issues: that is, push through structural adjustment, fiscal consolidation, and bank recapitalisation, on the one hand; and unify the framework for the Eurozone’s bank regulation, supervision, deposit insurance and resolution, on the other. Only these measures will decisively break the damaging feedback between weak sovereigns and weak banks and deliver the financial normality that will allow time for the Eurozone’s institutional framework to be further developed.

Overall, in Europe and elsewhere, the revitalisation of banks and the moderation of the financial industry will end their destructive interaction with other sectors and clear the way for the next steps – fiscal consolidation and the deleveraging of the private non-financial parts of the economy. Only when balance sheets across all sectors are repaired will virtuous cycles replace the vicious ones and the global economy move back to a balanced growth path.

This column is based on the analysis in the Bank for International Settlement’s 82nd Annual Report, published on 24 June 2012 (see here).

The views expressed here are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the BIS.

References

Prasad, Eswar and Karim Foda (2012), “A fragile and fickle recovery”, VoxEU.org, 23 April.