Although economic theory is still inconclusive as to the exact effect of integration on the properties of business cycle co-movement, a number of empirical contributions have argued that intense trade and financial integration is associated with a stronger degree of business cycle synchronisation (Bordo and Helbling 2003, Kose et al. 2003, Kose et al. 2003, 2008). A corollary of this view is that the Bretton Woods era – a period during which both trade and financial integration were substantially below both pre-WWI and current levels (Bordo et al.1999, Obstfled and Taylor 2004) – is often presented as the low point of business cycle synchronisation in history. But is it true that world co-moves more than it used to? And could it be that returning to the Bretton Woods world – with capital controls and fixed exchange rates – would decrease business cycle co-movement between countries?

In a recent paper (Monnet and Puy 2016), we show that because of important data limitation, the previous literature tended to minimise the amount of co-movement in real activity before 1973. Using a new database of quarterly industrial production index for 21 countries from 1950 to 2014 based on IMF archival data, two key findings emerge. First, we find the globalisation period is not associated with more output synchronisation at the global level. Contrary to the common wisdom, the world business cycle was as strong during Bretton Woods (1950-1971) than during the Globalisation Period (1984-2006) before the Global Crisis. Second, we find that, at least in normal times (i.e. absent a global financial crisis), deeper financial integration tends to de-synchronise national outputs from the world cycle.

The world factor – and its influence on national economies – since 1950

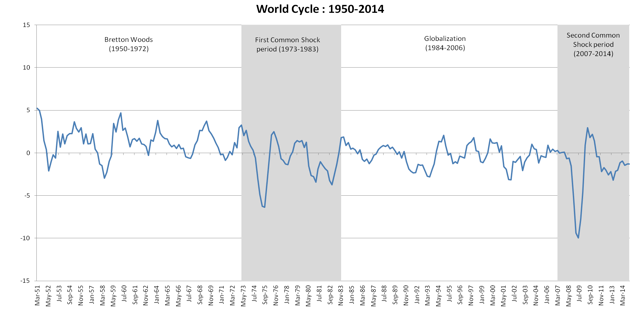

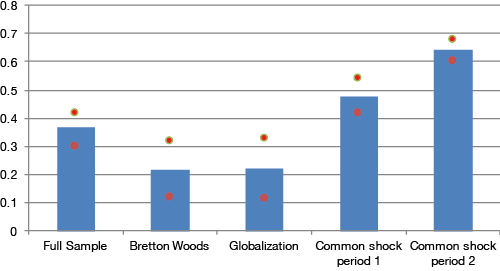

Building on Kose et al. (2003) and a new database of real activity since 1950, our research first shows that a very precise (common) world factor has been at play since 1950 (Figure 1), although its quantitative impact has varied significantly across different periods (Figure 2). As expected, we find that the importance of the world factor for national output dynamics increases dramatically during periods of common shocks (1972-1983 and 2007-2014). For instance, we estimate that between 2007 and 2014, 65% of the variance in output growth in our sample was due to the world factor, suggesting that almost no country moved on its own during that period. Contrary to the common wisdom however, we do not find any difference in co-movement between Bretton Woods (1950-1971) and the Globalisation Period (1984-2006). On average, the global dynamic accounts for 20% of output volatility in both periods. Among other things, this result shows that when a longer sample is used, we do not find empirical support for the view that globalisation, before the 2007-2008 financial crisis, was associated with more co-movement at the global level (e.g Kose et al. 2008).

Figure 1. World factor since 1950

Figure 2. Variance decompositions average – full sample vs. sub sample

Note that averages are computed across all 21 countries for each sub sample. Dots report the 5 and 95 percentiles of the posterior distribution

Why do some countries ‘de-synchronise’ while others ‘re-synchronise’?

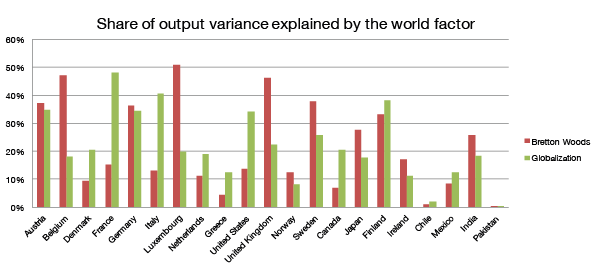

Another important finding of our research is that although the average co-movement we observe has not changed between Bretton Woods and the Globalisation Period, who co-moves with the rest of the world has changed substantially (Figure 3). Countries such as the UK, Belgium or Sweden, who were strongly co-moving with the rest of the world during Bretton Woods, have been significantly disconnected from the world dynamic during the Globalisation Period. In contrast, countries such as France, Italy and to a minor extent the US, who were dominated by idiosyncratic dynamics under Bretton Woods, have been re-synchronising with the world cycle. A significant number of countries are also found to display constantly low (or high) degree of synchronisation with the rest of the world in both periods.

Figure 3. Variance decompositions by country and sub-sample

Why do some countries synchronise while others de-synchronise? Our results show that the changes in synchronisation observed over the last 65 years can be explained, to a great extent, by both trade and financial integration patterns. In normal times, we find that deeper financial integration has a negative impact on the synchronisation with the world cycle. Quantitatively, we estimate that increasing financial integration by 10% – measured by the ratio of foreign assets plus foreign liabilities to GDP – decreases co-movement with the rest of the world by 1%. Interestingly, this ‘de-synchronising’ effect can be compensated by opposite forces in times of global financial stress (e.g. since 2007), during which more financially integrated economies co-move more than others. We also find that trade integration tends to increase co-movement with the rest of the world, although this effect disappears when considering only advanced economies, suggesting that trade integration only affects the strength of co-movement with the world at early stages of the process.

Conclusion

The Global Crisis reignited the debate on the importance of globalisation in shaping output co-movement (e.g. IMF 2013). Our research cast a new light on these issues in two ways. First, we find that the Bretton Woods era was not a period of low co-movement compared to the period between 1984 and 2006, which saw a massive rise in both trade and financial globalisation. Among other things, this implies that a low level of integration – imposed through the extensive use of capital controls and trade barriers - does not imply, per se, a low level of co-movement in the economic system.1 Second, we find a robust negative link between financial openness and the correlation with the world business cycle, although this effect is clearly dampened when financial crisis hit (e.g after 2007). Financial integration has a strong and asymmetric impact on output co-movement.2

Authors’ note: The opinions expressed herein are solely the responsibility of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting those of the IMF, Banque de France, the Eurosystem or anyone else associated with these institutions or their policies.

References

Bordo, M D, B Eichengreen, and D A Irwin (1999), “Is Globalization Today Really Different than Globalization a Hunderd Years Ago?”, NBER Working Paper, No.7195.

Bordo, M D, and T Helbling (2003), “Have national business cycles become more synchronized?”. NBER Working paper, No. 10130.

Cesa-Bianchi, A, J Imbs, J Saleheen (2016), “Finance and Synchronization”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 11037.

IMF (2013), "Dancing Together? Spillovers, Common Shocks, and the Role of Financial and Trade Linkages", World Economic Outlook, October, Chapter 3.

Kalemli-Ozcan, S, E Papaioannou, and F Perri (2013), “Global banks and crisis transmission,” Journal of International Economics 89(2): 495–510.

Kalemli-Ozcan, S, E Papaioannou, and J L Peydro (2013), “Financial Regulation, Financial Globalization, and the Synchronization of Economic Activity,” Journal of Finance 68(3): 1179–1228.

Kose, M A, E S Prasad, M E Terrones (2003). "How Does Globalization Affect the Synchronization of Business Cycles?". American Economic Review, vol. 93(2): 57-62, May.

Kose, A, C Otrok, C H Whiteman (2003), “International business cycles: world, region, and country-specific factors”. American Economic Review 93 (4): 1216–1239.

Kose, A, C Otrok, C H Whiteman (2008), “Understanding the evolution of world business cycles”. Journal of International Economics 75 (1): 110–130

Ayhan Kose, E Prasad, K Rogoff, S-J Wei (2006), "Financial Globalization: A Reappraisal", IMF Working Papers 06/189, International Monetary Fund.

Monnet, E (2014), "Monetary Policy without Interest Rates: Evidence from France's Golden Age (1948 to 1973) Using a Narrative Approach", American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 6(4): 137-69.

Monnet, E and D Puy (2015), “Foreign reserves and international adjustment under the Bretton Woods system: a reappraisal”, mimeo.

Monnet, E and D Puy (2016), "Has Globalization Really Increased Business Cycle Synchronization?", IMF Working Paper No. 16/54

Obstfeld, M, and A M Taylor (2004), Global capital markets: integration, crisis, and growth. Cambridge University Press.

Romer, C D, and D H Romer (2002), "A Rehabilitation of Monetary Policy in the 1950's ." American Economic Review 92(2): 121-127.

Endnotes

1 Further research is needed to understand fully how shocks did propagate during Bretton Woods. A hypothesis relates to the imperfect functioning of capital controls. Recent studies of central banking under Bretton Woods have also shown that monetary policy was more responsive to inflation and balance of payments than what is usually thought (Romer and Romer 2002, Monnet 2014). The narrative analysis we conduct in Monnet and Puy (2016) suggests that it was indeed a fundamental cause of common movements across countries. Monnet and Puy (2015) also re-assessed the adjustment problem of Bretton Woods which fuelled transmission of shocks trough fixed exchanged-rates.

2 This result echoes the recent empirical findings of the literature looking at correlations of country pairs (Kalemli-Ozcan et al. 2013, Kalemli-Ozcan et al. 2013). Cesa-Bianchi et al. (2016) also find an asymmetry although they define shocks differently.