On 23 June 2016, there will be a referendum to decide whether the UK should remain in or leave the EU. Proponents on both sides of the Brexit debate argue that the outcome will have important and long-lasting consequences. The latest Centre for Macroeconomics (CFM) survey focuses on the consequences for the stability of the UK financial sector.1

Long-term financial sector implications

Brexit is likely to have important consequences for the UK’s financial sector.2 Armstrong (2016) highlights several. If the UK were to leave the EU, then it may not have the same access to the Eurozone’s financial infrastructure, because the ECB may restrict euro-related activities of London-based banks.3

Proponents of Brexit argue that stability of the Eurozone will require greater integration and increased regulation. But changes that are desirable for the financial stability of the Eurozone are not necessarily beneficial for the UK financial sector. One could counter that the UK financial sector is unlikely to avoid being affected by Eurozone financial regulation if it continues to play such a dominant role in Eurozone finance. An objection against this last argument is that given the increasingly global nature of finance, future regulation will be heavily influenced by the G20 and the Financial Stability Board, and the UK has an influential role in these bodies.

Another issue is the right of UK-based financial institutions to conduct business anywhere in the EU. These ‘passporting rights’ would disappear in the event of Brexit, which would mean that financial institutions currently in the UK (whether UK- or foreign-owned) would need to establish EU-based operations.[4 Those in favour of remaining in the EU argue that this would reduce the competitiveness of the City. Those in favour of leaving the EU counter that these extra costs are small and that the benefits of being in a large financial centre such as London (so-called ‘agglomeration effects’, such as an abundance of experienced financial sector workers and support businesses) easily outweigh them.5

Finally, it has been argued that the EU-imposed cap on bonuses is not effective at improving financial stability, and that it reduces the competitiveness of UK financial services vis-à-vis non-EU financial service centres. Leaving the EU would allow the UK to revoke this cap.

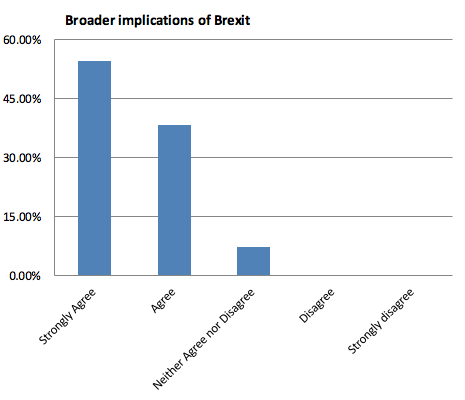

Question 1: Do you agree that there would be substantial negative long-term consequences for the UK financial sector if the UK were to leave the EU?

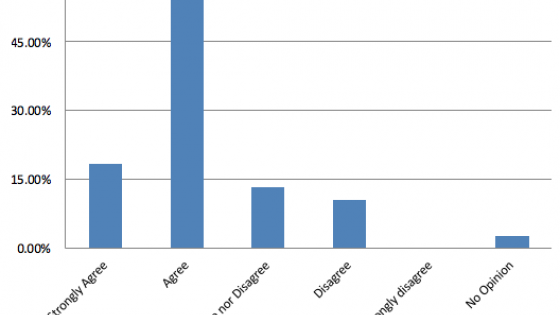

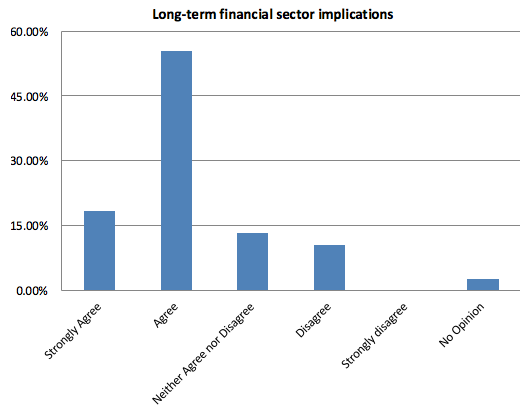

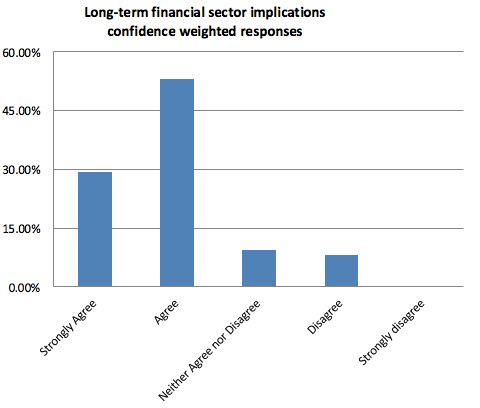

Thirty-eight of the panel answered this question, and a strong majority agree with the statement: 18% strongly agree, 55% agree, 13% neither agree nor disagree, and 11% disagree. When weighted with self-assessed confidence, 82% either strongly agree or agree and only 8% disagree. It is very unusual that the panel members are so united in their views.

The two main arguments given by those who agree with the view that Brexit would have negative long-term consequences for the UK financial sector are the following.

First, losing privileged access to the Eurozone financial infrastructure is likely to reduce business opportunities for UK-based financial institutions. In particular, several panel members argue that the likely loss of passporting rights will hurt the UK financial sector. Indeed, several participants agree with Morten Ravn (University College London) that the loss of passporting rights will “set in motion a process of relocation” of some (large) banks to the Eurozone.

In addition, Jagjit Chadha (NIESR) and Ray Barrell (Brunel) point out that this privileged access enabled UK banks to benefit from ECB’s liquidity operations during the financial crisis and Brexit would make such benefits less likely in the future.

The second main argument given to support the view that Brexit will be damaging to the UK financial sector is related to regulation. As Angus Armstrong (NIESR) points out, “it is clear that the EU will be responsible for financial regulation within the EU (within the context of G20, FSB, etc). The UK would have to comply with regulations which it would have only a consultative role in shaping.”

Moreover, UK-based financial may face tougher regulation for euro-related activities. For example, Ray Barrell (Brunel) writes “the current EU financial regulation environment has a single market in financial services that does not coincide with the regulatory area under the control of the ECB. Although this is unwise, it is of benefit to the UK. Once the UK has left the EU, the ECB will tidy this up, and the UK financial system will find itself with the same access as the US, and hence firms will move.”

Among those who do not believe that Brexit will seriously hurt the UK financial sector, two kinds of arguments are given. First, some believe that current arrangements will not be affected very much. Gianluca Benigno (London School of Economics, LSE) writes “if the UK were to seek to join the EEA [European Economic Area] adopting a model like Norway, the UK could continue to take advantage of the passport system and would maintain existing regulation.”

The second argument given by several panel members is that there is no credible alternative for the skills and experience of the UK financial sector. Even though Sir Charles Bean (LSE) thinks that Brexit will have some negative consequences, he writes “London will still retain the attractions of deep markets and a skilled workforce.”

Short-term financial instability

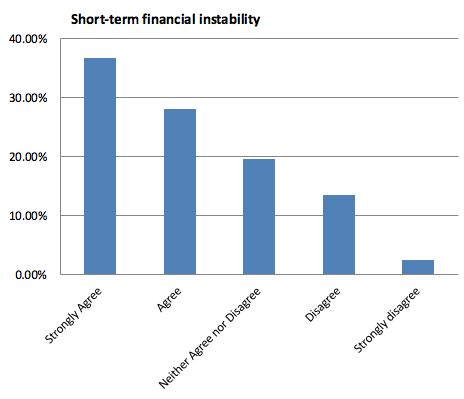

The first question focuses only on long-run consequences for the financial sector. This question focuses on the short-run financial instability that a vote for Brexit would be likely to generate.

A vote in favour of Brexit on 23 June would not result in the immediate withdrawal of the UK from the EU. Instead, the UK government would invoke Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty and have up to two years to withdraw.

At the moment of the referendum result, there would be uncertainty about future arrangements with the EU. For example, we would not know about the UK’s future trade relationships with the EU and other countries and they would become subject to negotiation. Similarly, product, labour and financial market regulations would all be subject to some uncertainty. Such economic uncertainty can have a big impact on the investment and hiring decisions of firms (Bloom 2009).

Here we focus on the effects of Brexit on financial markets that would be likely to be affected by both the implications of Brexit for UK economic prosperity, as well as by the uncertainty itself.

With this question, we want to get an assessment of the likelihood of a severe financial disruption. This question is not about some increased volatility during the weeks immediately following the vote. The type of disruption that we are thinking of is the kind that will make headlines in newspapers for at least several months, will put the Bank of England on high alert, and will be most likely to require some non-trivial intervention by policy-makers.

For example, on 16 May 2016, in its 2016 Article IV Consultation Concluding Statement, the IMF stated:6

“Another risk is that markets may anticipate such adverse economic effects, provoking an abrupt reaction to an exit vote that effectively brings these costs forward. This could entail sharp drops in equity and house prices, increased borrowing costs for households and businesses, and even a sudden stop of investment inflows into key sectors such as commercial real estate and finance. The UK’s record-high current account deficit and attendant reliance on external financing exacerbates these risks. Such market reactions could sharply contract economic activity, further depressing asset prices in a self-reinforcing cycle.”

One could counter this alarming prediction with the observation that the UK economy including its financial sector are doing well and that the financial markets may see some advantages in an upcoming Brexit.

Question 2: What is the probability that the UK experiences such a significant disruption to financial markets and asset prices following a vote for Brexit on 23 June?

- > 70%.

- 31-70%

- 11-30%

- non-trivial but ≤10%

- ≈ 0%

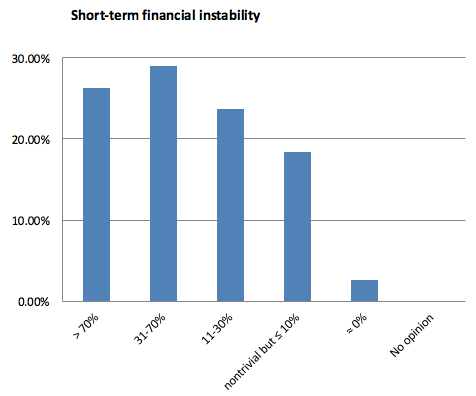

Thirty-eight panel members answered this question. The results are shocking. The panel members are extremely worried about the consequences of a Brexit outcome for financial markets.

The question asked about the likelihood of a “significant disruption” and the background information pointed out that the question is about a “severe financial disruption” that would “put the Bank of England on high alert and will be most likely to require some non-trivial intervention by policymakers.” Nonetheless, there is only one panel member, Michael Wickens (Cardiff and York), who thinks that the chances of such serious disruptions are basically zero. He writes “Like most of the predicted economic gloom this too is an exaggeration. More significantly, the point of Brexit is long-term, largely non-economic benefits, not short-term costs.”

All of the other panel members think that there is at least a non-trivial chance of a serious financial breakdown: 26% think that the chance is higher than 70%, 29% think this probability is between 31% and 70%, 24% think it is between 11% and 30%, and 18% think that it is less than 10%, but still non-trivial. The picture becomes gloomier when answers are weighted with (self-assessed) confidence. Then 37% of the respondents think that the probability is above 70%. One important qualifier is that several panel members point out that it is very difficult to predict how financial markets will react.

Ricardo Reis (LSE) points out that financial markets themselves are predicting quite a bit of turbulence if the Brexit campaign were to win the referendum. He writes “implied volatility in sterling/dollar three-month option contracts is very high (around 14%, which is 1.5 times higher than in January) while the betting markets for Brexit seem to put its odds at around 20%. Combining these two numbers, it seems that financial markets think the unlikely event of Brexit would lead to significant disruption in the value of sterling.”

Several of our experts emphasise the uncertainty associated with a Brexit outcome. Panicos Demetriades (Leicester) writes “This event will unleash the kind of uncertainty that Keynes had in mind when he said “we simply do not know” when referring to the likely effect of war. Such uncertainty can only be disruptive for financial markets. We will enter a new era of volatility that is likely to last until these difficult negotiations are completed.”

The panel members see this uncertainty as not just related to new arrangements with the EU. Costas Milas (Liverpool) writes “Bearing in mind that Tory Eurosceptics have made substantial noise during the Brexit campaign, it is more likely than not that we will witness political instability.” But some panel members think that the policy response will be adequate. Jonathan Portes (NIESR) writes “I am reasonably confident that the authorities have contingency plans in place, and the appropriate tools, to deal with the most adverse possible impacts.”

Richard Portes (London Business School, LBS) highlights the current unfavourable external position of the UK: “We are running a current account deficit of 6-7% of GDP, financed by portfolio capital inflows and FDI [foreign direct investment]. It is highly likely that there would be a ‘sudden stop’ to these capital flows, a sharp depreciation of sterling, and a sharp fall in asset prices. We would no longer be the ‘safe haven’ that we have been in ‘risk off’ episodes of recent years.”

Panel members who think that the chance of another financial crisis is non-trivial but not very high point out that there are some mitigating factors. Sir Charles Bean (LSE) writes “While a period of asset price volatility is very likely after a vote for Brexit, including a further substantial fall in sterling, I do not expect to see a major cut-off in funding to UK financial institutions. Banks and other financial institutions already cope with the risk of substantial movements in exchange rates, so I do not expect disruption on that score. Also a vote to leave should not be associated with a sharp deterioration in the quality of banks' assets.”

Overall Brexit consequences

The first two questions focused exclusively on the financial sector. We added a third question to the survey, because some panel members’ opinions may be different when the overall economic consequences of a Brexit outcome are considered and they may want to make that known.

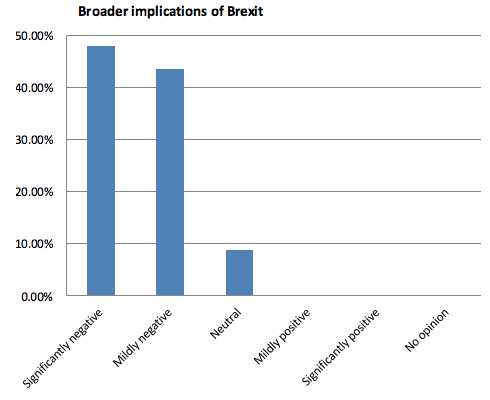

Question 3: What do you think will be the overall economic consequences of Brexit for the UK?

- Significantly negative

- Mildly negative

- Neutral

- Mildly positive

- Significantly positive

Twenty-three panel members answered this question and nobody answered that the overall consequences of a Brexit outcome would be beneficial for the UK economy. It is noteworthy that – for the first time since the start of this survey – one side of the argument is supported by none of the panel members.

There is, however, disagreement on how large these negative effects will be. In particular, there is disagreement on the impact on trade. Several panel members think that the new arrangements between the EU and the UK will be such that trade will not be affected very much. After all, as Jonathan Portes (NIESR) points out, “Economists agree that trade, migration and access to large markets are good for economies.”

But some economists are more pessimistic about the types of arrangements that the UK can expect. For example, Panicos Demetriades (Leicester) writes “The UK will eventually negotiate a deal that is bound to be much less favourable for UK industry and financial services than EU membership, partly to make sure that the precedent that is set deters other countries from leaving.”

Moreover, there is disagreement on whether the negative effects are long-term effects. As Paolo Surico (LBS) points out, “In the long run, it would seem difficult to build a definite compelling argument for either front. But in the short run, there seems to be mounting evidence that the economic consequences of Brexit would be significantly negative with the concrete possibility of significant capital flows and sharp drop in asset prices, including houses and the exchange rate.”

References

Armstrong, A. (2016) ‘EU Membership, Financial Services and Stability’, National Institute Economic Review May: 31-38.

Bloom, N. (2009) ‘The Impact of Uncertainty Shocks’, Econometrica 77: 623-85

[1] Full survey results are available at: http://cfmsurvey.org/

[2] The May 2016 issue of the National Institute Economic Review, published by the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, provides a lot of useful background information. It also has been helpful for the background information given in this survey: http://www.niesr.ac.uk/publications/eu-membership-financial-services-and-stability#.V0MU6mZVSHl

[3] One example is the regulation and oversight of central counterparties (CCPs), which have become a very important part of the financial infrastructure following the global financial crisis. The current arrangement is that the Bank of England and the ECB have joint oversight of CCPs and there are reciprocal currency swaps to facilitate multi-currency liquidity support. This arrangement was the outcome of a long process as the ECB was not initially supportive since the arrangement facilitates a high proportion of euro-denominated financial activities taking place abroad. If the UK were to leave the EU, then the arrangement may not continue, which is likely to have a negative effect on the importance of the UK financial sector for euro-related financial transactions.

[4] Passporting rights guarantee the right to sell into the rest of the EU without having a branch there.

[5] http://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2016/02/12/brexit-would-not-bring-an-apocalypse-to-city-interests/

[6] https://www.imf.org/external/np/ms/2016/051316.htm