In China, both a labour shortage and unemployment have emerged as problems in recent years. The number of university students scheduled to graduate in June 2014 is 7.27 million, increasing with 280,000 from 2013 (MHRSS 2014). Following 2013 – at the time considered the most difficult year for job seekers in history – 2014 is expected to be even harsher. Problems in the labour market in China, which is a key region for Japanese companies advancing overseas, are also attracting attention in Japan. This paper provides a few perspectives on the Chinese labour market, which combines a labour shortage with challenges for job seekers.

High unemployment amid a labour shortage

Although a nationwide labour survey did not include unemployment rates, we will look at the Chinese labour market using statistics from job placement services.1 According to the latest statistics on job offers and applications, as of the January-March quarter of 2014, there were 1.293 million young job seekers who graduated in the last year or earlier but had yet to find a job through employment agencies in 102 major cities (MHRSS 2014). As the population of these major cities accounts for approximately 46.7% of the total population of large and mid-size Chinese cities, we can estimate that the number of young job seekers who have graduated, but have yet to find a job, totals more than two million.

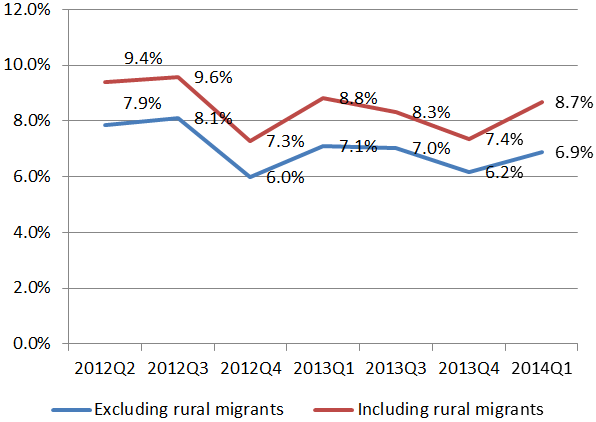

Using data from the survey, I also tried to estimate the unemployment rate in those 102 major cities. I employed data on the working population in major cities and the number of job seekers who have not found employment (newly graduated unemployed persons and rural immigrant job seekers) based on the international standard set by the International Labour Organisation (see Figure 1).2,3

Figure 1. Unemployment rate in major Chinese cities

Source: Calculated by the author from statistics on job placement services in China (http://www.chinajob.gov.cn/).

The unemployment rate, including rural migrants in major cities in the first quarter of 2014, is 8.7%, while that excluding them is 6.9%. Unemployment rates before the first quarter of 2014 are also close to these numbers, suggesting that the high unemployment rate has continued.

The unemployment rate is high not because unemployed people lack the ability to work. Looking at the age distribution of all job seekers in these 102 major cities (of whom 96.0% are unemployed), workers aged 45 or younger account for 89.9% of the unemployed, indicating a large population of young workers. In addition, 54.7% of job seekers have specialist or vocational qualifications. Regarding the type of job, 44.1% of job seekers look for technical jobs, while 25.8% seek marketing, sales, or service jobs. There still exists abundant, high-quality labour in the Chinese labour market.

Job offers still buoyant

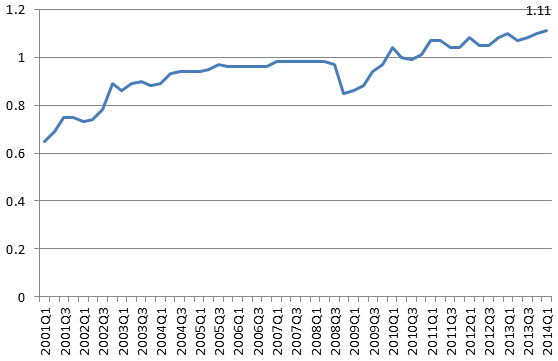

The high unemployment rate cannot be blamed for the sluggish job offers. Despite the slower economic growth, job offers from companies are still buoyant. As indicated in Figure 2, the job-offers-to-seekers ratio in the first quarter of 2014 was 1.1, showing that there are still more job offers than job seekers.

Figure 2. Job-offers-to-seekers ratio in China

Source: Statistics on job placement services in China (http://www.chinajob.gov.cn/) and CEIC Database

With regard to the buoyant job offers, I demonstrated in my recent book (Liu, 2013a) that labour productivity is the most persuasive of the factors that have an impact on the job-offers-to-seekers ratio in China. As shown in search theory, the larger the income earned from a job, the larger will be the rate of return gained from job creation for companies, which will result in more job offers. Given that productivity in developing countries will improve through not only technological innovations on their own but also through their efforts to catch up with developed nations, a higher rate of increase in productivity can be expected. For that reason, even if the economy slows down somewhat, buoyant job offers are likely to continue because of the support for higher productivity.

Reasons why a labour shortage coexists with high unemployment

So why do labour shortage and high unemployment co-exist in China? I analysed this in my book. More specifically, I explored the matching efficiency in the labour market by estimating the matching function between job offers and job seekers in urban labour markets in China based on search and matching theory.

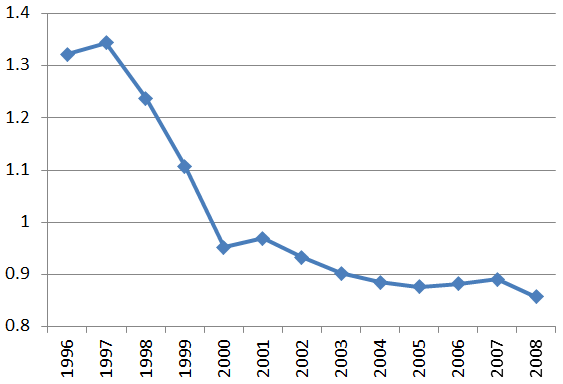

Figure 3 shows the values of matching efficiency on the vertical axis. From the figure, we see that matching efficiency in China declined sharply from the late 1990s to the 2000s.

Figure 3. Matching efficiency in the Chinese labour market

Source: Liu (2013 a, b)

- A conceivable cause of the sharp decline is the increase of the inflow and outflow of workers into and out of companies, reflecting the establishment of new companies and the disappearance and downsizing of old state-owned enterprises following economic and corporate reforms, which led to friction in the labour market. This decline was also attributable to imperfect information between job offers and job seekers.

- I also found that a rise in productivity has a significant negative impact on matching efficiency and showed that a mismatch has arisen between unemployed persons and companies seeking highly-skilled workers.

- Lastly, although it was not dealt with by quantitative analysis in the book, a skill mismatch and a geographic mismatch have some bearing on this phenomenon.

For example, the job-offers-to-seekers ratio for security maintenance staff is surprisingly high in Nanjing at 4.0, while it is only 0.2 in Shanghai.

One way to improve matching efficiency is through employment agencies, as I find that the matching efficiency is very high in areas where there are many employment agencies. As employment agencies are organisations that provide information mainly on job offers and job seekers, they are useful for increasing matching efficiency by correcting imperfect information. Although it is, of course, difficult to increase substantially the number of employment agencies in a short period of time, it would be beneficial for companies to put more efforts into recruiting activities in order to bring many job seekers and secure the labour force.

Although the coexistence of unemployment and labour shortage is seemingly contradictory, it is observed in labour markets not only in China but also in many other countries. Even though it is impossible to eliminate imperfect information in the actual economy, there is room for improvement. If the matching efficiency in the labour market increases, it seems possible to lower both the labour shortage and the unemployment.

Favourable conditions for Japanese companies in China

The main reason why Japanese companies invest overseas has already shifted from cheap labour to local demand for products. The “Survey of Overseas Business Activities” of the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (2014) shows that while the percentage of Japanese companies that place emphasis on cheap labour has fallen to 21.4%, the percentage of companies that value demand for products in a country which they have entered, and its three neighbouring countries, is 66.7% and 27.4%, respectively. The abundant university-educated labour force that exists in China despite the labour shortage appears to create favourable conditions for Japanese companies – emphasising the quality of human capital and innovation in an investment destination.

Editors’ note: This column was reproduced with permission from the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI).

References

Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (2014), “Survey of Overseas Business Activities”.

MHRSS (2014), Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security of the People's Republic of China, China Employment.

Liu, Y (2013a), China's Urban Labour Market: a Structural Econometric Approach, Kyoto University Press & Hong Kong University Press.

Liu, Y (2013b), "Labour Market Matching and Unemployment in Urban China", China Economic Review, Vol.24, pp.108-128.

Footnotes

1 The full name of the unemployment rate reported in China is the ‘registered unemployment rate’, which includes only unemployed persons registered by the government. One of the conditions required for registration is the urban household registration. As it is difficult to acquire the urban household registration outside of one’s birthplace, it is believed that there are many people who are not included in the registered unemployment rate although they are effectively unemployed.

2 For job seekers, those who take on a job are tallied in an independent statistical item. Therefore, they are not included in an item such as rural immigrant job seekers.

3 In China, as workers with rural household registration are given the right by the government to use land, they are assumed to have an agricultural profession. However, as their family already is farming, there are people who cannot take on an agricultural job and, as a result, there is a surplus of labour among them. Despite the right to use land, they do not engage in agriculture effectively and look for work in the cities. Therefore, in this column, two unemployment rates are calculated by distinguishing these job seekers in rural areas.