A failing bank can be defined as one that has insufficient capital. Bank capitalisation strategies thus are crucial in determining the probability of a bank failure. Confirming this, Berger and Bouwman (2013) find that higher levels of pre-crisis capital increase a bank’s probability of survival during a banking crisis. Beltratti and Stulz (2012) and Demirguc-Kunt, Detragiache and Merrouche (2013) find that banks that were better capitalised before the crisis had a better stock-market performance during the crisis.

Banks are subject to regulatory requirements in the form of minimum capital ratios. All the same, banks enjoy considerable discretion in their capitalisation policies. In a new paper (Anginer, Demirguc-Kunt, Huizinga, and Ma 2013), we examine how a bank’s corporate governance affects its capitalisation for an international sample of banks over the 2003-2011 period.

Value-maximising shareholders are likely to favour relatively low bank capitalisation, as this increases a bank’s prospects of receiving generous bailouts in the event of a future bank failure. Consistent with this, our main finding is that ‘good’ corporate governance – or corporate governance that makes the bank act in the interest of bank shareholders – engenders lower bank capitalisation.

Recent bank capitalisation trends

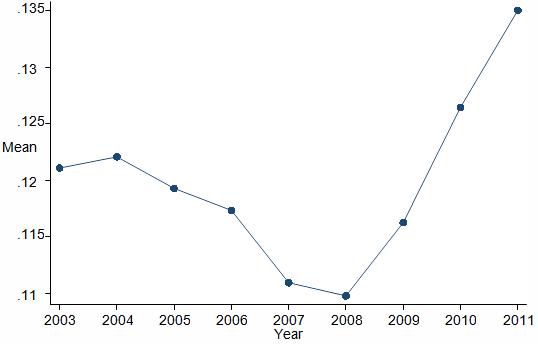

Average bank capitalisation ratios declined materially during the recent financial crisis of 2007-2009, with varying degrees of recovery in subsequent years. To illustrate this, the Tier 1 capital ratio, which is a regulatory capital ratio constructed as Tier 1 capital divided by risk-weighted assets, is seen to decline from 2004 to 2008 in Figure 1. In subsequent years, the Tier 1 capital ratio increased to levels even higher than before the crisis.

Figure 1. Yearly mean of the ratio of Tier 1 capital to risk-weighted assets

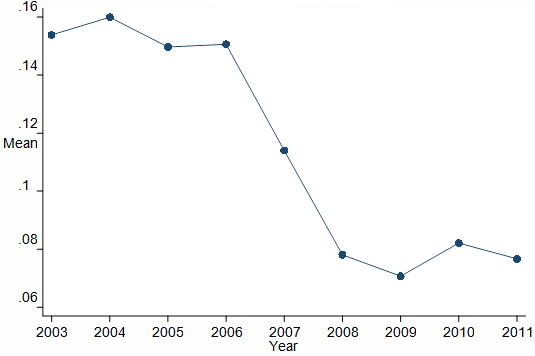

The common equity ratio, defined as the book value of common equity divided by total assets, similarly declined during the crisis till 2009, with only a modest subsequent recovery (see Figure 2).

The subdued recovery of the common equity ratio – relative to the Tier 1 capital ratio – suggests that the rapid recovery of the latter ratio is as much due to a decline in the average risk-weighting of assets, as to an actual increase in capital.

Figure 2. Yearly mean of the ratio of the book value of common equity to total assets

To complement the picture, we graph the ratio of the market value of the bank’s common equity to the estimated market value of a bank’s total assets in Figure 3. This market-based capitalisation ratio should be more accurate than measures solely based on accounting data, if bank stock investors are aware of any distortions in the accounting valuation of bank assets.

Figure 3. Yearly mean of the ratio of the market value of common equity to the estimated market value of total assets

Interestingly, the time paths of the common equity ratio in Figure 2, and the market value ratio in Figure 3, look very similar until 2010, while they diverge in 2011 as the uptick in the common equity ratio in that year is not accompanied by a comparable increase in the market value ratio. Bank accountants apparently have been more sanguine about the improvement of bank capitalisation in the aftermath of the crisis than bank stock investors.

Good corporate governance yields low bank capitalisation

A key corporate governance feature is board size, i.e. the number of board members. The relationship between board size and bank capital is theoretically ambiguous, as a larger board may be better able to represent shareholder interests because it is less easily captured by management, but on the other hand it may be less effective in promoting shareholder interests due to free rider problems within the board. We find that bank capitalisation is lowest for boards of intermediate size, consisting of about 10 members.

- Hence, it appears that boards of intermediate size best serve shareholder interests in engineering low bank capitalisation, leading to higher bank valuation.

- As to board composition, we find that bank capitalisation is lower if the roles of chief executive officer and chairman of the board are separated, i.e. if the chief executive officer is not also the chairman of the board.

Such a separation may enable the board to lower bank capital in the interest of bank shareholders without effective opposition from the chief executive officer. CEO-chairman separation is estimated to reduce the common equity ratio by 0.3% in 2006, just prior to the recent financial crisis. This reduction is material, given that the common equity variable has an overall average value of 8.9%.

As a related matter, we consider whether local corporate law allows for the possibility of anti-takeover measures to be taken by a bank. The possibility of anti-takeover provisions could lead to higher bank capital, as a weaker market for corporate control implies that management can more easily pursue banking strategies that do not maximise shareholder value, such as a high bank capitalisation. Our results confirm that anti-takeover provisions lead to higher bank capitalisation.

- Overall, we find evidence that good corporate governance favouring shareholder interests – implying boards of intermediate size, CEO-chairman separation, and a lack of anti-takeover provisions – leads to lower bank capitalisation, with possibly negative implications for financial stability.

Implications for the design of corporate governance at banks

In reform discussions since the crisis, the potentially nefarious impact of good corporate governance on bank risk-taking often fails to be recognized. Looking back at the crisis, the European Commission (2010, p. 6), for instance, concludes that the board of directors of a bank were unable to exercise effective control over senior management, and that directors’ failure to understand and ultimately control the risks to which their financial institutions were exposed, was at the heart of the origins of the crisis. This assessment ignores that more effective control of the board over senior management may lead to more, rather than less bank risk brought on, for instance, by lower bank capitalisation.

The UK Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards (2013, p. 40 and p. 42) similarly concludes that many non-executive directors failed to act as an effective check on, and a challenge to, executive managers, recommending the appointment of a Senior Independent Director, ensuring that the relationship between the CEO and the Chairman does not become too close, and that the Chairman performs his or her leadership and challenge role. Our evidence suggest that the introduction of such a Senior Independent Director could well lead to more bank risk through lower bank capital.

In specific cases, bank supervisors move to bring about good governance at a bank, with possibly opposite consequences for bank risk from the ones that were intended. In October 2013, Jamie Dimon, for instance, gave up his chairmanship of the board of J.P. Morgan Chase’s main banking subsidiary at the instigation of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. However, the resulting separation of Dimon’s previous roles of CEO (of the parent bank) and chairman (of the subsidiary bank) at J.P. Morgan Chase potentially has the unintended effect of increasing bank risk.

Conclusions

The finding that good corporate governance leads to low bank capitalisation does not necessarily imply that corporate governance schemes at banks should not be designed to be good. In the end, the disadvantage of good corporate governance in bringing about lower bank capitalisation has to be balanced against any presumed benefits in terms of restricting management’s ability to perform badly in unrelated ways, for instance, by shirking or acquiring perks at the expense of bank shareholders.

Authors' note: This column’s findings, interpretations, and conclusions are entirely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank, its Executive Directors, or the countries they represent.

References

Anginer, Deniz, Asli Demirguc-Kunt, Harry Huizinga, and Kebin Ma (2013), “How does corporate governance affect bank capitalization strategies?”, CEPR Discussion Paper 9674.

Beltratti, Andrea, and Rene M. Stulz (2012), “The credit crisis around the globe: Why did some banks perform better?”, Journal of Financial Economics 105, 1-17.

Berger, Allen N., and Christa H. Bouwman (2013), “How does capital affect bank performance during financial crises?”, Journal of Financial Economics 109, 146-176.

Demirguc-Kunt, Asli, Enrica Detragiache, and Ouarda Merrouche (2013), “Bank capital: Lessons from the financial crisis”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 45, 1147-1164.

European Commission (2010), “Green paper on corporate governance in financial institutions and remuneration policies”, COM(2010) 284 final, Brussels.

Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards (2013), “Changing banking for good, final report”, UK Parliament, London.