Holding non-controlling minority shares in other companies not for investment but for strategic purposes – that is, building trusting relationships as a basis for future business transactions – is a customary business practice rooted in Japanese corporate culture. Japan’s Corporate Governance Code, released by the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) in 2015, provides that companies engaging in the practice of such strategic shareholding “should disclose their policy with respect to doing so” from the viewpoint of promoting the efficient use of capital and the creation of corporate value.

Meanwhile, concerning the follow-up of Japan’s Stewardship Code and Japan’s Corporate Governance Code, the Financial Services Agency’s Council of Experts pointed to problems on the part of investee companies or those allowing their shares to be held by business partners, which are outside the ambit of the codes. More specifically, council members raised concerns over the possibility of strategic shareholding being used for anticompetitive purposes because, depending on the power balance in business relationships, a company can reduce pressure from its shareholders by asking its business partners to hold its shares. Following the introduction of the Stewardship Code, institutional investors’ influence on decision making at shareholder meetings has increased relative to that of other shareholders, as the code calls for the proper exercise of voting rights by institutional investors. In contrast, strategic shareholders are, in most cases, perceived to be friendly shareholders who readily cast yes votes for management’s proposals. Corporate managers often receive harsh feedback from institutional investors. Thus, the significant presence of strategic shareholders may give rise to moral hazard on the part of corporate managers, giving them leeway to avoid confronting institutional investors.

Strategic shareholding in Japan

Strategic shareholdings can take various forms, such as unilateral holdings, cross holdings, and circular holdings involving three or more companies. However, the term ‘strategic holding’ is too often taken as a synonym for ‘cross holding,’ spreading the perception that such inter-locking relationships have mostly been resolved. According to Nihon Keizai Shimbun’s morning edition of 24 June 2017, the percentage of cross-held shares has dropped below 10%. However, this is the ratio based on the aggregate market value of shares with the scope of shareholders limited to listed companies excluding life insurers.

Ryoko Ueda examined the actual state of strategic shareholdings based on information disclosed in annual securities reports for the fiscal year ended March 2016, using the Bank of Japan’s Flow of Funds Accounts Statistics and Japan Exchange Group’s survey on the distribution of shareholdings as references (Ueda 2016). Specifically, the ownership structure of companies listed on the TSE First Section, expressed in terms of a percentage of voting rights, was scrutinised as a factor hindering dialogue between companies and shareholders.

With respect to shares held strategically, companies are required to disclose in their annual securities reports the number of shares held, the value recognised on the balance sheet, and the specific purpose of holding them for each of the top 30 issues. Meanwhile, information on own shares strategically held by other companies is not subject to any disclosure requirements. However, it is assumed that listed companies’ investor relations and other staff responsible for organising shareholders’ meetings are aware of who the strategic shareholders of their companies are, because of the need to predict the voting behaviour of shareholders.

Thus, for the purpose of our study, we classified shareholders into three types – ‘strategic shareholders,’ ‘institutional investors,’ and ‘others’ – and examined how the ownership structure of companies listed on the TSE First Section has changed over the past ten years, based on information (shareholdings by type of shareholders, major shareholders) disclosed in their annual securities reports. Strategic shareholders here are defined as including the central and local governments, life insurers, banks, and business corporations; whereas institutional investors are domestic pension funds, investment trusts, and foreign corporations; others are then securities firms, individuals, etc., as well as those holding their own shares.

We classified foreign corporations as institutional investors based on the presumption that foreign companies investing in Japanese listed companies are mostly institutional investors. Securities firms, individuals, and so on were included as others because it is difficult to distinguish between shareholdings for strategic purposes and those for purely investment purposes in the case of the former, and between shareholdings by founding families and those held by general shareholders in the case of the latter. For instance, it is quite possible that some portions of shareholdings held by strategic shareholders are purely for investment purposes. However, determining the purpose of shareholdings is difficult in reality. Thus, we classified shareholdings by type of shareholders. Our study inevitably has its limitations because of the limited availability of information disclosed by issuers regarding their shareholders’ purposes.

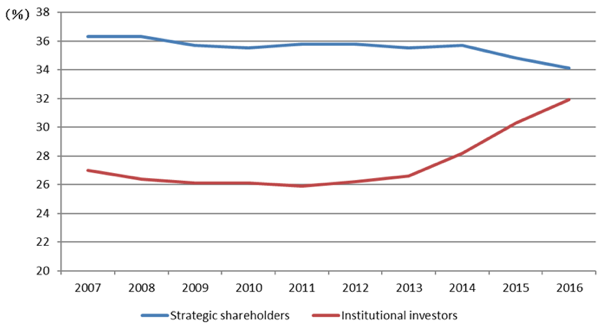

Findings from our study show that strategic shareholders and institutional investors accounted for 36.3% and 27.0% respectively in 2007. Reflecting subsequent changes in awareness regarding corporate governance and the efficient use of capital, the percentage of strategic shareholders decreased to 34.1% in 2016, whereas that of institutional investors increased to 31.9%. However, the presence of strategic shareholders remains significant (Figure 1). Business corporations accounted for roughly three quarters of strategic shareholders, while insurers and banks almost evenly split the remaining quarter, with the central and local governments having minimal presence.

Figure 1 Ownership structure of TSE first section companies

Source: Ueda (2016).

The evolving strategic shareholding situation

Although strategic shareholdings are often defined as a problem unique to Japan, similar practices have been observed in some other countries. In France, following the privatisation of state-owned enterprises under the regime of President Francois Mitterrand in the 1980s, concerns over the possibility of hostile takeover bids from foreign companies prompted many French companies to engage in the practice of cross shareholding.

Meanwhile, in Germany, financial institutions such as banks and insurance companies were traditionally engaged in the practice of cross shareholding among themselves, and/or that of strategic shareholding in business corporations. However, as part of capital market reform in the 2000s, the government of Chancellor Gerhard Schröder eliminated the capital gains tax on stock sales. The policy facilitated the unwinding of cross shareholdings, resulting in a decrease in the percentage of structural or strategic shareholders, mostly financial institutions, and an increase in the percentage of institutional investors.

Likewise, in Japan, the percentage of strategic shareholders has been on a declining trend over the past ten years as shown in the aforementioned survey, reflecting the growing awareness among companies of the problematic aspects of strategic shareholdings following the introduction of relevant disclosure requirements and codes. As a possible measure to accelerate this move, the provision of certain incentives such as tax incentives in Germany is worthy of consideration.

In general terms, strategic shareholdings among listed companies are undesirable because such a practice tends to result in an inefficient use of capital, as well as hindering dialogue between companies and investors. Meanwhile, in specific terms, there may be cases that are likely help improve corporate value. When foreign companies with global operations invest in other companies, their intent is to acquire a controlling stake in most cases, that is, except where they are unable to do so due to restrictions on foreign ownership.

However, in the Japanese corporate culture, it is not rare for companies to hold shares in other companies as part of technical or business partnerships without affecting each other’s independence in management. Such shareholdings may be a testing ground for possible business integration in the future. In the case of listed companies, the effect of such shareholdings is to place otherwise freely marketable shares under fixed ownership. Thus, if they are to hold shares in other listed companies or have their shares held by others, they should be responsible for explaining, in more specific and explicit terms, how such shareholdings will contribute to their business strategy and corporate value in the future.

Meanwhile, the Stewardship Code, as revised in May 2017, has introduced a requirement for institutional investors to disclose their proxy voting decisions for each investee company. There is growing concern among Japanese companies that institutional investors, which already give little consideration to the specific circumstances of investee companies, may become even more stereotyped in making voting decisions in response to the new disclosure requirement.

This in turn gives rise to the concern that companies may reinforce their efforts to secure strategic shareholders in an attempt to smooth the way for having their proposed resolutions approved by the shareholders’ meeting. This is contrary to the intended purpose of the Stewardship Code, which aims to facilitate the sustainable growth of companies through constructive dialogue with institutional investors. Institutional investors’ efforts to make the dialogue more useful to companies are also crucial to dispelling this concern.

Conclusion

Corporate governance reform, which aims to help companies achieve sustainable growth by ensuring sound governance by shareholders, is an important element of Japan’s growth strategy, and the effectiveness of dialogue between companies and their shareholders is at the core of the reform. Based on this viewpoint, we hope to continue to see extensive discussion on the issue of strategic shareholdings.

Editor's Note: This column is reproduced from the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) with some modification.

Reference

Ueda, R (2016), Antei Kabunushi no Bunseki [Analysis of Strategic Shareholders], Shoji Homu.