In a recent article and VoxEU.org report, Acemoglu et al. (2012a, b) advance a provocative thesis about cuddly versus cut-throat capitalism. The authors note the many positives of cuddly capitalism embraced by the Nordics, where society is more egalitarian and social safety nets are stronger, but they also suggest that reduced incentives for innovation mean that these economies will have lower income levels and innovation rates than cut-throat frontier economies like the US. Acemoglu et al. (2012a, b) find that these trade-offs make welfare ambiguous in an integrated world, but also argue that it may not be possible for countries like the US to be as cuddly as the Nordics while still being the innovation leader.

Maliranta et al. (2012) recently raise some question marks about whether the Nordic economies are actually less innovative than the US. While accepting some praise and acknowledging some call to action with respect to Nordic policies, Maliranta et al. (2012) also argue that by a number of measures, there is not an innovation gap between the cuddly and cut-throat countries, so that perhaps the differences across forms of capitalism are not so stark.

We do not debate the US versus the Nordics – instead, we only look at variation across Europe (Bozkaya and Kerr 2013). And, we mostly take a pass on the question of how cuddly a country wants to be – that becomes a control variable. We instead ask whether some mechanisms of implementing cuddliness are more conducive to entrepreneurship and innovation than other techniques, using the lens of venture capital investments. Most European governments want to support venture capital and entrepreneurial ecosystems, as a step towards more innovative economies. Holding constant cuddliness, are there mechanisms that support worker insurance and also allow for venture capital markets to emerge?

The trade-off and why it matters for venture capitalists

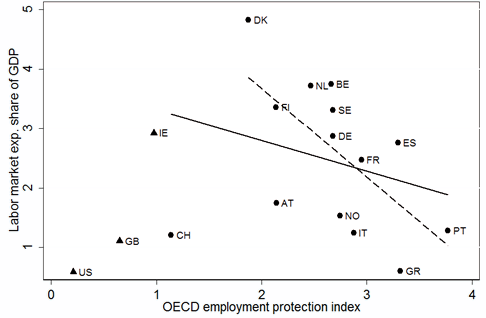

The central policy trade-off considered is whether worker insurance is provided through labour-market expenditures (e.g. unemployment insurance benefits, worker retraining) or through employment protection. Figure 1 shows that European economies substitute between these two approaches. All countries in Continental Europe provide substantially higher levels of support on both policies than the US or other Anglo-Saxon economies, à la cuddly and cut-throat capitalism. Yet, the trend line, which is calculated for Continental Europe only, shows that they tend to favour one policy over the other. Countries that have high labour expenditures tend to have weaker employment protection.

Figure 1. Trade-off in worker policies

Notes: Figure illustrates the policy trade-offs between employment protection and labour-market expenditures over the 1990-2008 period. The solid trend line describes the policy trade-off for Continental European nations; the dashed line excludes Switzerland, which has insurance policies more similar to the Anglo-Saxon economies. European nations that favour employment protection systematically have lower labour-market expenditures.

Does this policy choice matter for venture capitalist investment and the high-growth entrepreneurs they support? We draw out several reasons why it might. While the implications of employment protections are debated for many outcomes like overall employment levels and technical efficiency, the theoretical and empirical work makes it clear that employment protections slow down the labour adjustments that firms make (Autor et al. 2007). Employment protection results in labour-adjustment costs to firms that reduce job separations and hiring rates.

These adjustment costs contrast sharply with labour-market expenditures and unemployment insurance benefits that also provide worker insurance but do not tax separations directly. Thus, firms have greater flexibility in their hiring and firing if worker insurance is provided through labour-market expenditures. General taxation may need to be higher to support labour-market expenditures, but this taxation is shared throughout the economy, rather than concentrated on one margin. This difference creates the friction for venture-capitalist investors.

- First, the types of sectors in which venture capitalists specialise – characterised by high growth and high volatility – are disadvantaged, all else being equal, when worker insurance is provided via employment protection rather than through labour-market expenditures;

Several theory models note how innovation and high-tech sectors can be discouraged by these adjustment taxes (e.g. Saint-Paul 2002, Samaniego 2006).

- Second, labour-adjustment costs weaken the specific business models of venture capitalist investors over-and-above these market size effects;

Successful venture capitalist investors maintain a portfolio of projects and reallocate resources aggressively from failing ventures to high-performing investments. This staged approach yields option values for investments, and venture capitalist investors close under-performing ventures for the sake of better opportunities. Strict employment protection increases the costs of these labour adjustments and closures, weakening the venture capitalist model.

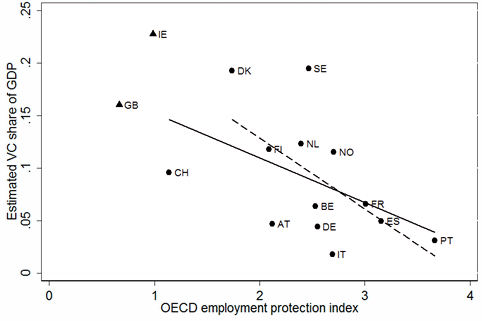

Figure 2 shows indeed that policy choices like employment protection are correlated with venture capitalist placement.

Figure 2. Implications for venture capitalist (VC) investors

Notes: Figure illustrates the lower venture-capitalist investments in countries with higher employment-protection mandates over the 1990-2008 period.

The detailed stuff

Graphs are pretty, and the conceptual argument is not too complex. Of course, to publish a paper on this, one needs to do much more. In Bozkaya and Kerr (2013) we further demonstrate the deeper connection behind these scatter plots:

- Using data from Amadeus and Venture Xpert, we show empirically that venture capitalist-backed firms in Europe have higher labour volatility than their peers. This need for more rapid adjustments among venture capitalist portfolio companies is central to our argument about why these policies matter. We also show that the typical venture capitalist investments in countries that favour employment protection tend to be ‘safer’, i.e. older, greater revenues, fewer employees, and less dynamic. This is indicative of these marginal costs biting.

- We construct a panel of investments in 15 countries and 14 sectors over the 1990-2008 period. We order sectors by their inherent labour volatility as measured in the US. The above policy trade-off is evident in three sets of variations.

- First, the cross-sectional distribution of investments across countries and sectors similar to the Rajan and Zingales (1998) methodology.

- Second, a country-level longitudinal response to policy changes similar to Blanchard and Wolfers (2000).

- Third, a differential longitudinal response across sectors within a country.

- This latter triple-differencing pushes the Rajan and Zingales framework to also capture longitudinal changes. It shows that countries that shift towards more flexible worker insurance policies see their strongest venture-capitalist investment growth in sectors with high inherent labour volatility, controlling for the worldwide growth in investment by sector.

- We demonstrate these results using the base policies graphed in Figure 1, and we also devise two indices to separate the level of worker insurance provided (aggregating over the underlying policies) from the mechanisms used to provide the insurance (the strength to which policies allow flexible labour markets). These transformed indices provide a cleaner empirical platform that we also link to our theory model.

Conclusion

The extent to which nations want to be cuddly or not is a very complicated choice, involving many economic and non-economic factors. We make the very simple observation that the mechanisms chosen to implement this desired worker insurance level can have very different implications for the development of venture capitalist markets, which every European government claims it wants to do.

References

Acemoglu, Daron, James Robinson, Thierry Verdier (2012a), “Cuddly or Cut-Throat Capitalism: Choosing Models in a Globalised World”, VoxEU.org, 21 November.

Acemoglu, Daron, James Robinson, Thierry Verdier (2012b), “Can’t We All Be More Like Nordics? Asymmetric Growth and Institutions in an Interdependent World”, NBER Working Paper 18441, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Autor, David, William Kerr, and Adriana Kugler (2007), “Does Employment Protection Reduce Productivity? Evidence from US States”, Economic Journal 117(521), 189-217.

Blanchard, Olivier, and Justin Wolfers (2000), “The Role of Shocks and Institutions in the Rise of European Unemployment: The Aggregate Evidence”, Economic Journal 100, C1-C33.

Bozkaya, Ant, and William Kerr (2013), “Labor Regulations and European Venture Capital”, Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, forthcoming.

Maliranta, Mika, Niku Määttänen, and Vesa Vihriälä (2012), “Are the Nordic Countries Really Less Innovative than the US?”, VoxEU.org, 19 December.

Rajan, Raghuram, and Luigi Zingales (1998), “Financial Dependence and Growth”, The American Economic Review 88(3), 559-586.

Saint-Paul, Gilles (2002), “Employment Protection, International Specialization, and Innovation”, European Economic Review 46, 375-395.

Samaniego, Roberto (2006), “Employment Protection and High-Tech Aversion”, Review of Economic Dynamics 9, 224-241.