As most people know, the general trend in the dollar’s role as an international currency has been slowly downward since 1976. International use of the dollar as a currency in which to hold foreign-exchange reserves, to denominate financial transactions, to invoice trade, and to serve as a vehicle for foreign-exchange transactions is below where it was during the heyday of the Bretton Woods era (1945-1971). However, few are aware of what the most recent numbers show.

It is not hard to think of explanations for the downward trend:

- Since the time of the Vietnam War, US budget deficits, money creation, and current-account deficits have often been high.

Presumably as a result, the dollar has lost value in terms of other major currencies and in terms of purchasing power over goods.

- The US share of global output has declined.

- The disturbing willingness of some US congressmen in October to pursue a strategy that would have the Treasury default on legal obligations has led some observers to question the dollar’s international currency status.

- Some Emerging Market currencies are joining the list of international currencies for the first time.

Indeed, some analysts have suggested that the Chinese yuan may rival the dollar as the leading international currency by the end of the decade! (See Eichengreen 2011.)

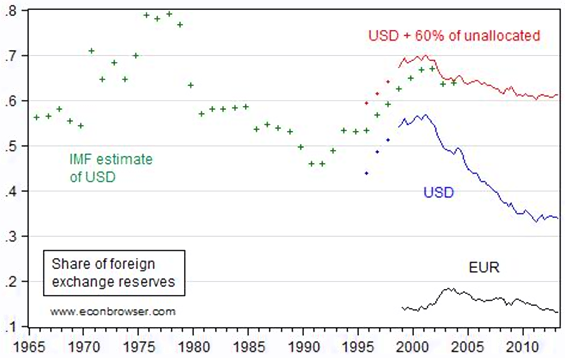

The dollar’s trend as an international currency has not been uniformly downward, however. The periods when the public is most concerned about the issue do not coincide well with the periods when the dollar’s share is in fact falling. By the criteria of international use as a reserve currency among central banks and as vehicle currency in foreign exchange markets, the most rapid declines took place during the intervals 1978–1991 and 2001–2010. (The yen and deutschemark were the rising currencies during the first period, and the euro during the second.)

In between these two intervals, during the years 1992–2000, there was a clear reversal of the trend, notwithstanding a popular orgy of dollar declinism around the middle of that decade. Central banks held only an estimated 46% of their foreign exchange reserves in the form of dollars in 1992, but had returned to almost 70% by 2000.

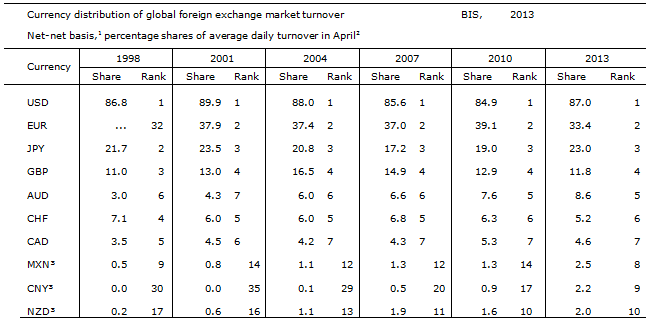

Subsequently, the long-term downward trend resumed. According to one estimate, the share in reserves declined from about 70% in 2001 to barely 60% in 2010 (Chinn 2013). During the same decade, the dollar’s share in the foreign exchange market also declined – the currency constituted one side or the other in 90% of foreign-exchange trading in 2001, but only 85% in 2010.

Pause in the decline of the dollar’s role

The most recent statistics unexpectedly suggest that the dollar’s standing has again taken a pause from its long-term decline. The International Monetary Fund reports that its share in foreign exchange reserves stopped declining in 2010 and has been flat since then. If anything, the share is up very slightly thus far in 2013 (International Monetary Fund 2013). Similarly, the Bank for International Settlements reported in its recent triennial survey (Bank for International Settlements 2013) that the dollar’s share in the world’s foreign-exchange markets rose from 85% in 2010 to 87% in 2013 (preliminary global results). That the dollar has been holding up so well comes as a surprise, in light of dysfunctional US fiscal policy. Or maybe we should no longer be surprised. After all, when the global financial crisis erupted out of the American sub-prime mortgage mess in 2008, the reaction of global investors was to flee into the US, not out. They clearly still regard the US Treasury bill market as the safe haven, and the dollar as the top international currency.

A lack of alternatives

The explanation must be the one that is so often noted – the absence of good alternatives. In particular, the euro has its own all-to-obvious problems. Indeed, the euro’s share of reserve holdings and its share of foreign-exchange transactions have both fallen by several percentage points over the last three years (reserves from 28% of allocated reserves in 2009 and 26% in 2010, to 24% in the most recent 2013 figures; forex trading from 39% of transactions in 2010 to 33% in 2013).

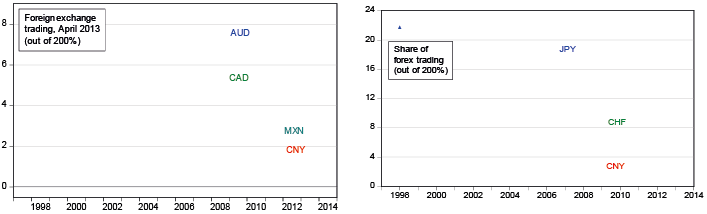

What about the vaunted yuan? According to the IMF statistics, it hasn’t yet broken into the ranks of the top seven currencies in terms of central bank reserve holdings. The top six are the US dollar and the euro, followed by the yen and the pound (the latter quietly reclaimed the number three position in 2006, and has been running neck-and-neck with the yen recently), and the Canadian and Australian dollars (also running neck-and-neck). According to the Bank for International Settlements statistics, China’s currency has finally broken into the top ten in forex trading, but its share is only 2.2% of transactions. This is behind the Mexican peso at 2.5%, and still further behind the Canadian dollar, Australian dollar, and Swiss franc. (See Table 1 and Figures 2 and 3).

Since 2.2% is much less than China’s share of world trade, it would be more accurate to say that the renminbi is becoming a normal currency than to say that it is becoming an international currency – let alone the top international currency. Despite recent moves by the Chinese government, the yuan still has a long way to go. Of the three attributes that a currency needs to become widely used internationally, the yuan has two – size of the home economy and the ability to hold its value – but still lacks the third: deep, liquid, open financial markets.

What accounts for the recent stabilisation of the dollar’s status?

What do the last three years have in common with the preceding period of temporary reversal, 1992–2000? Both intervals saw striking improvements in the US budget deficit, both structural and overall. The federal deficit is now less than half what it was in 2009 or 2010, and the record deficits of the 1980s were converted into record surpluses by the end of the 1990s. Perhaps the fiscal observation is a coincidence.

It would be foolish to read too much into two historical data points. It would be even more foolish to believe, just because US politicians have failed to dislodge the US dollar from its number one status over the last 40 years, that they could not accomplish the job with another few decades of effort.

The pound sterling had the top spot in the nineteenth century, only to be surpassed by the dollar in the first half of the 20th century (Eichengreen 2005). It is not an eternal law of nature that the US currency shall always be number one. The day may come when the dollar too succumbs in its turn. But that day is not today.

Figure 1. The dollar’s share in central bank reserve holdings stopped declining in 2010-2013.

Source: Chinn (2013), from IMF’s Currency COFER.

Table 1. The dollar’s share in foreign exchange trading has risen since 2010

Source: Bank of International Settlements’ Triennial Central Bank Survey, September 2013.

Figures 2 and 3. The yuan’s share has risen, but still ranks low

Source: Menzie Chinn. Data from Bank for International Settlements Survey. (For larger image of figures, click on 2 and 3.)

Editor’s note: This is an extended version of a Project Syndicate op-ed.

References

Bank for International Settlements (2013), “Triennial Central Bank Survey – Foreign Exchange Turnover in April 2013: preliminary global results”, Monetary and Economic Department, September.

Chinn, Menzie (2013), “What Currencies are Foreign Exchange Reserves Held In?”, Econbrowser, 31 October.

Chinn, Menzie and Jeffrey Frankel (2007), “Will the euro Eventually Surpass the Dollar as Leading International Reserve Currency?”, in Richard Clarida (ed.), G7 Current Account Imbalances: Sustainability and Adjustment, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Eichengreen, Barry (2005), “Sterling’s Past, Dollar’s Future: Historical Perspectives on Reserve Currency Competition”, NBER Working Paper No. 11336, May.

Eichengreen, Barry (2011), “The Renminbi as an International Currency”, Journal of Policy Modeling, 33(5): 723–730.

Frankel, Jeffrey (1995), “Still the Lingua Franca: The Exaggerated Death of the Dollar”, Foreign Affairs, 74(4): 9–16.

Frankel, Jeffrey (2012), “Internationalization of the RMB and Historical Precedents”, Journal of Economic Integration, 27(3): 329–365. (Summarised in RIETI and Vox.)

International Monetary Fund (2013), “Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER)”, 30 September.