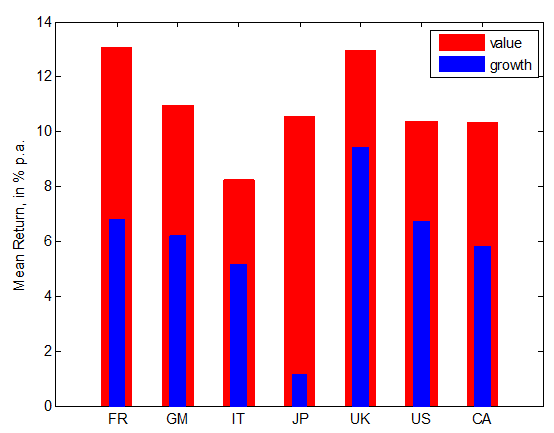

Value stocks, i.e. stocks of firms with high book-to-market, earnings-to-price, cash-earnings-to-price or dividend-to-price ratios, tend to earn higher average returns compared with growth stocks, i.e. stocks of firms with low respective ratios. Figure 1 shows average annualised returns on value (red) and growth (blue) portfolios for G7 countries over the sample period from January 1975 to December 2010. These data are freely available on the website of Kenneth R French.

Figure 1. Average portfolio returns

Why do stocks with different price-to-fundamentals ratios earn vastly different returns? Asset pricing theory claims that high returns should reflect a premium for assets’ risk exposure: stocks that tend to pay off poorly in bad economic times should offer on average higher returns. It is well known, however, that standard benchmark models in finance, such as the CAPM, demonstrate virtually no power to explain systematic differences in returns on value versus growth stocks. This phenomenon is therefore often referred to as a 'value anomaly'. Apparently, conventional models fail to understand and correctly identify the true underlying fundamentals which drive risk premia and explain cross-sectional patterns in returns on equity stock markets.

Two components of downside risk: Theoretically

In a recent paper I suggest one possible explanation for this puzzle (Galsband, 2012). I start with the basic insight that agents care differently about downside losses as opposed to upside gains (Ang et al. 2006). Finance theory predicts that risk-averse investors are willing to hedge against unexpected economic downturns. What are the sources of downside market fluctuations? Campbell and Vuolteenaho (2004) show that the market can fall because of 'bad' (long-lasting) news to future cash flows or because of 'good' (short-lived) news about higher future market rates applied to discount these cash flows. Intuitively, stocks that are sensitive to the former sort of market news are more risky and should promise higher returns. A simple link between equity return and downside risk called 'downside beta' cannot distinguish between these sources of fluctuations. I therefore argue that the aggregate downside beta hides more than it reveals. The distinction between 'bad' downside risks such as a sudden permanent drop in dividends and 'good' downside risks such as an unexpected rise in interest rates is a key to explain higher average returns on value as opposed to growth stocks.

Two components of downside risk: Empirically

To test this hypothesis, I employ a four-beta decomposition of Botshekan et al. (2012) which breaks assets’ upside and downside betas in their 'bad' and 'good' components. Using robust econometric methods, each value and each growth portfolio risk can be disentangled into four components: downside cash flow, upside cash flow, downside discount rate, and upside discount rate risks measured by the respective 'betas'. In line with recent evidence for the US, I document a strong relation between assets’ average returns and their 'bad' cash flow and 'good' discount rate downside betas. In particular, international value stocks react strongly to long-lasting downside shocks but are much more resilient to short-lived downside shocks. International growth stocks, meanwhile, are much more sensitive to transitory short-lived downside shocks. These findings are best visualised graphically. Figure 2 illustrates that value stocks (red) have systematically higher loadings on downside cash flow risk than growth stocks (blue) across the G7 countries. In fact, this pattern holds true for a larger number of economies including the US, Canada, and 12 major EAFE (Europe, Asia, and the Far East) markets. Using extensive asset pricing tests, I show that 'bad' downside betas are associated with a robust risk premium.

Figure 2. 'Bad' downside betas

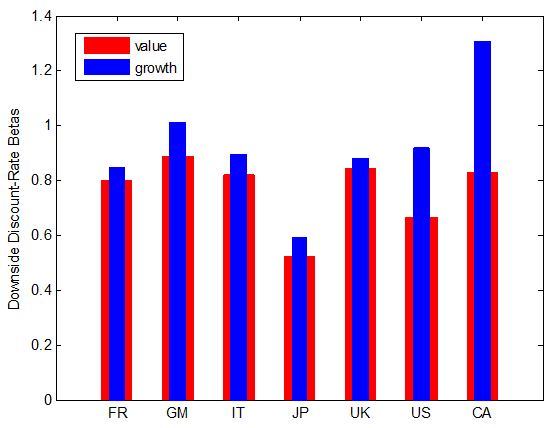

In contrast, Figure 3 demonstrates that growth stocks (blue) tend to display a greater co-movement with market 'good' downside fluctuations than value stocks (red). Most interestingly, cross-sectional asset pricing tests point out that international stock exposure to the 'bad' downside risk is rewarded with a higher compensation than assets’ loadings on 'good' downside risk. This result is consistent with the main insight of the intertemporal asset pricing theory and reveals common sources of systematic risk in equity returns that is reflected in the market cash-flow component.

Figure 3. 'Good' downside betas

Conclusions

The column argues that downside market risk can explain systematic differences in returns on value and growth stocks on international equity markets. The key is to distinguish between 'bad' and 'good' downside market shocks. Agents require a greater risk compensation for sensitivity to long-lasting (permanent) against short-lived (transitory) downside shocks. Recognising this difference can prevent investors from overweighting value as opposed to growth stocks when building their portfolios. High average returns on international value stocks (i.e. stocks with low price-to-fundamentals ratios) reflect their strong sensitivities to the market’s permanent downside shocks. In contrast, growth stocks (i.e. stocks with high price-to-fundamentals ratios) hide exposure towards less dangerous downside risk. Finally, severe risks related to downside fluctuations in the market’s cash flows carry a premium which is pervasive and statistically significant.

References

Ang, A, J Chen, and Y Xing (2006), “Downside Risk”, Review of Financial Studies, 19(4): 1191-1239.

Botshekan, M, R Kraeussl, and A Lucas (2012), “Cash Flow and Discount Rate Risk in Up and Down Markets: What is Actually Priced?” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, forthcoming.

Campbell, J Y and T Vuolteenaho (2004), “Bad Beta, Good Beta”, American Economic Review 94(5): 1249-1275.

Galsband, V (2012), “Downside Risk of International Stock Returns”, Journal of Banking and Finance 36(8): 2379-2388.