On the heels of the crisis, sovereign risk premium differentials in the euro area have been widening. Although the perceived risk of default for euro-area countries remains generally low, financial markets appear to have been increasingly discriminating among government issuers while requiring overall higher risk premiums (Figure 1). Specifically, the spreads on the yield on 10-year government bonds over Bunds spiked in January 2009 for various euro-area members, accompanied by downgrades of sovereign debt ratings for Greece, Spain, and Portugal and a warning for Ireland. The rebound of euro-area sovereign spreads is particularly noticeable from a historical perspective, as it follows a prolonged period of remarkable compression of sovereign risk premium differentials, which had been raising doubts about financial markets’ ability to provide fiscal discipline across euro-area members.

Figure 1. Selected euro-area sovereign spreads, June 2008-09 (in basis points)

In this context, the observed widening of sovereign spreads might reflect increased financial markets’ concerns about the worsening fiscal accounts of most euro-area countries following the financial crisis. Indeed, while the use of public resources has been critical to stem further job losses and to break the adverse loop between the financial system and the real economy, it has also implied a significant deterioration in the budget positions of most euro-area members and ballooning government debts.

In addition to fiscal vulnerabilities and subsequent default risk concerns, discrimination among sovereign issuers may reflect considerations about the relative liquidity of different government bond markets. Indeed, the financial turmoil may have led to a flight to safety and liquidity, resulting in a decline in the yields of the most liquid sovereign bond markets – such as the benchmark Bunds. The literature tends to recognise the importance of liquidity risk in explaining interest rate differentials within the euro area, although the size of this effect remains somewhat controversial (Codogno et al. 2003, Beber et al. 2009, ECB 2009, Manganelli and Wolswijk 2009).

Government exposure to weaknesses in the financial sector may have also become a factor in explaining sovereign spreads in the euro area (Mody 2009, Ejsing and Lemke forthcoming). In this respect, some countries have committed large resources to guarantee financial institutions, thereby establishing a potentially important link between financial sector distress and public sector bailouts. In Ireland, for example, sovereign spreads started to increase after the government extended a guarantee to the banking system.

Global risk repricing may have also contributed to the widening of sovereign risk premium differentials, in a sign of discrimination among different classes of default risk. Owing to the abrupt reversal in market sentiment and the severe liquidity squeeze, euro-area sovereign bond markets have certainly come under strain. Previous empirical studies have indeed found that spreads tend to co-move over time and are mainly driven by a single time-varying common factor, typically identifying international risk appetite (Geyer et al. 2004, Haugh et al. 2009, Favero et al. forthcoming).

Understanding what has prompted recent developments in sovereign risk is critical for policymaking. If the observed widening of sovereign spreads mainly mirrors an abrupt reversal in market sentiment due – for instance – to a severe liquidity squeeze, liquidity provision measures will prompt knock-on beneficial effects on governments’ marginal funding costs. Else, if rising sovereign spreads reflect financial markets’ concerns about the solvency of national banking systems and their consequences for fiscal sustainability, investors will keep requiring higher sovereign default risk premiums for most countries and discriminating among sovereign issuers until a credible financial system restructuring plan and a clear commitment to long-run fiscal discipline are envisaged.

Dissecting common risk

To estimate the extent to which (unobservable) shifts in international risk appetite may have contributed to the (observed) increase in sovereign spreads for the individual countries, we rely on a very simple asset pricing model (Lombardi and Sgherri, forthcoming). By assuming that risk premiums embedded in country-specific sovereign yields are determined jointly in the market and influenced by both the riskiness of the specific asset and the common price of risk, the latter component can be identified and thereby filtered out (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Estimated common component in sovereign spreads (in basis points)

To a first approximation, the estimated common risk component seems able to capture four distinct developments in euro area sovereign bond spreads: the narrowing of risk premiums differentials due to EMU convergence over 2001-02, the decline in financial market volatility over 2003-05, the abundant liquidity and muted risk aversion characterising international financial markets over 2005-07, and the jarring risk repricing commencing end-2007 and receding at the very end of the sample.

Which economic forces are behind the movements in such a time-varying common factor? Common shifts in euro-area risk premium differentials are found to be associated with expectations about the state of the economy and uncertainty in financial markets. Risk aversion increases as economic downturns loom on the horizon – that is, when inflation is expected to decline and monetary policy to be accomodative – while it decreases in periods of forthcoming expansion – when the opposite holds true. The intuition behind this is certainly not new. As the economy enters recession, investors will take less risky positions in financial markets, as their income is already at risk. Hence, spreads seem to react to the uncertainty triggered by the economic slowdown rather than to incentives linked to monetary policy.

Explaining developments in euro-area sovereign risk during the crisis

To assess the determinants of spreads during the crisis, we estimate a simple panel model of the spread between the yield on ten-year sovereign bonds between ten euro-area countries and Germany using monthly data from January 2003 to March 2009.

Overall, our estimates show that changes in sovereign default risk premiums continue to reflect mainly global risk factors – such as shifts in risk aversion in financial markets. There is also evidence, however, that the sensitivity of sovereign spreads to projected debt changes significantly increased after September, suggesting that the markets may now be able to provide more fiscal discipline than in the early years of the common currency. In a few countries, markets also appear to be progressively more concerned about the solvency of national banking systems. Finally, the liquidity of sovereign bond markets appears to remain a relevant factor in explaining spread behaviour.

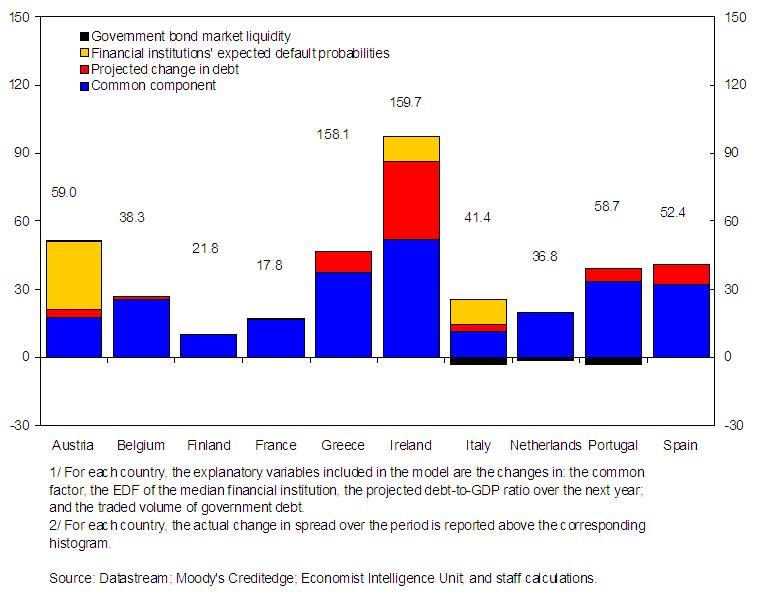

Country-specific issues also matter (Figure 3). Decomposing the contributions to the actual change in country-specific sovereign spread between end-January 2009 and end-September 2008 indicates that concerns about fiscal sustainability are significant for countries like Greece, Ireland, Spain, and – to a lesser extent – Austria, Italy, and Portugal. The extent to which rising default risks in the financial sector translate into increases in government spreads is found to be large and significant in Austria, Ireland, and Italy. Finally, ceteris paribus, the liquidity of the sovereign bond market appears to lessen Italian government’s financing costs. Nonetheless, a sizable part of the actual change in spreads since September 2008 remains unexplained, notably in the case of Greece.

Figure 3. Contributions to the change in spreads, January 2003-January 2009 (change end-January 2009 over end-September 2008, in basis points)

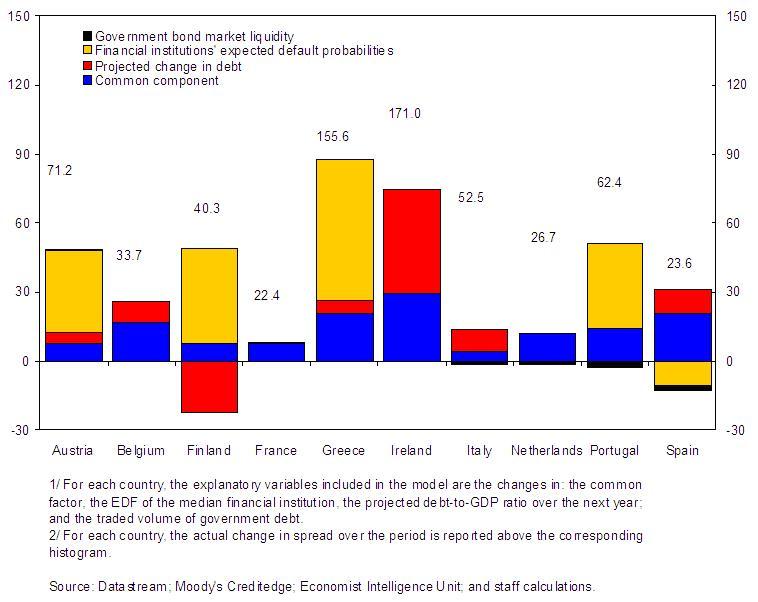

The picture has changed substantially, though, from end-January to end-March 2009 (Figure 4). Investors’ risk appetite appears to play a much smaller role by end-March, while concerns about the solvency of the national financial sectors have risen, particularly in Austria, Finland, Greece, and Portugal. On the other hand, concerns about domestic fiscal sustainability have mounted in Belgium, Ireland, and Italy. This seems to indicate an improvement in market’s perception of the euro-area cyclical outlook starting from 2009Q2 but, at the same time, it suggests that markets have become progressively more concerned about the potential fiscal implications of national financial sectors’ frailty and future debt dynamics. The liquidity of sovereign bond markets still seems to play a significant (albeit fairly limited) role in explaining changes in euro-area spreads in few countries.

Figure 4. Contributions to the change in spreads, January 2003-March 2009 (change end-March 2009 over end-September 2008, in basis points)

Conclusions

There is evidence that financial markets are increasingly sensitive to country-specific solvency concerns, and that has important implications for policymaking. In particular, it seems to support the position that restoring trust in the financial system is key – not only to shape the recovery, but also to increase the effectiveness of fiscal stimulus measures while reducing future governments’ financing costs. At the same time, it strengthens the argument for a credible commitment to long-run fiscal discipline and a clear exit strategy from a supportive policy stance as the crisis abates. Casting short-term fiscal expansion within a credible medium-term framework and envisaging fiscal adjustments as economic conditions improve could conceivably help euro area governments curb solvency concerns in financial markets. Structural reforms – enhancing potential growth and, thereby, medium-term revenue prospects – are also likely to work in the same direction. Together, these measures may be able to ensure that yesterday’s global financial crisis does not sow the seeds of tomorrow’s vicious domestic debt dynamics.

References

Beber, A., M. Brandt, and K. Kavajecz (2009), “Flight-to-quality or flight-to-liquidity? Evidence from the euro-area bond market,” Review of Financial Studies, 22, 925–57.

Codogno, L., C. Favero and A. Missale (2003), “Yield spreads on EMU government bonds,” Economic Policy, 18, 505–32.

Ejsing, J. and W. Lemke (forthcoming), “The Janus-headed salvation: sovereign and bank credit risk premia during 2008-09,” ECB Working Paper Series.

European Central Bank, (2009), “New evidence on credit and liquidity premia in selected euro area sovereign yields,” Monthly Bulletin, Box 4, September.

Favero, C., M. Pagano and E-L. von Thadden (forthcoming), “How does liquidity affect bond yields?,” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis.

Geyer, A., S. Kossmeier and S. Pichler (2004), “Measuring systematic risk in EMU government yield spreads,” Review of Finance, 8, 171–97.

Haugh, D., P. Ollivaud, and D. Turner (2009), “What drives sovereign risk premiums? An analysis of recent evidence from the Euro Area,” OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 718.

Lombardi, M. and S. Sgherri (forthcoming), “Risk repricing and spillovers across assets,” IMF Working Paper.

Manganelli, S. and G. Wolswijk (2009), “What drives spreads in the euro area government bond market?,” Economic Policy, 24, 191–240.

Mody, A. (2009), “From Bear Sterns to Anglo Irish: How Eurozone sovereign spreads related to financial sector vulnerability,” IMF Working Paper, No. 09/108.

Sgherri, S., and E. Zoli (2009), “Euro Area Sovereign Risk During the Crisis,” IMF Working Paper, No. 09/222.