The risk of a Greek exit from the Eurozone looms large. A breakaway by one country would increase the risk of a Eurozone breakup, with all individual countries reverting to their original currencies, but would not make it inevitable.

- A Greek breakaway has become a distinct possibility;

- A Eurozone breakup is still a tail risk.

The distinction is important because the two have very different implications.

- A Greek breakaway would have devastating consequences for the country’s economy and social fabric; but if the Eurozone firewalls hold, collateral damage to the global economy would be limited.

- A full Eurozone breakup, on the other hand, would see the European financial system implode in a domino of sovereign and corporate defaults; the Eurozone would enter a deep multi-year recession; Germany would share the region’s fate, with its banking system crippled and its main export markets collapsing; replacing the world’s second reserve currency with a plurality of new currencies would cause chaos in global financial markets.

The aftermath of Lehman’s collapse would look like a walk in the park.

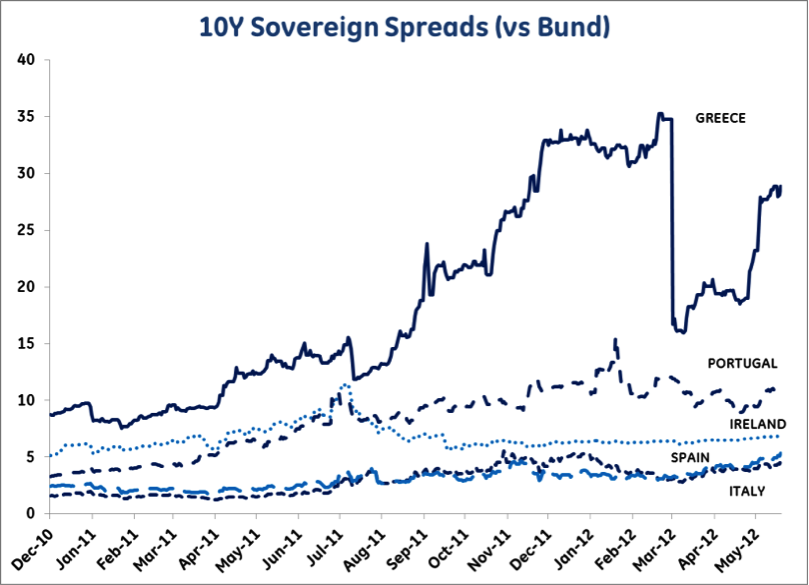

A background of recession and popular resentment has emboldened some Greek politicians to argue that austerity is unjustly imposed by Europe, and that Europe can be scared into weakening its conditions. EU politicians, the ECB, and even the IMF have openly acknowledged that a Greek exit is a possibility. Greek spreads have widened by close to 13 percentage points from the post-debt restructuring lows (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Ten-year sovereign spreads (vs Bund)

What next?

In the best-case scenario, Greek voters will realise that the choice is between staying in the Eurozone or exiting – not between staying in the Eurozone with reforms or without. A new reform-oriented government will take power after the 17 June elections, the EU and IMF will agree to a modest weakening of conditions, and tensions will be defused. Signals so far are mixed. Recent polls look a bit more promising for the pro-reform parties; but they continue to show that an overwhelming majority of Greek citizens want to both stay in the Eurozone and to renegotiate the current EU/IMF programme.

The biggest risk, however, is not that anti-reform parties can persuade Greek voters – it’s that they can persuade their EU partners that they are serious about their intentions. If the EU, ECB, and IMF become convinced that the required adjustment is politically unsustainable, they could conclude that Greek Eurozone membership is unsustainable as well. The thread is too thin for this sword of Damocles to hang above the euro indefinitely.

- The more likely an eventual Greek exit appears, the more rational it becomes for the Eurozone to allocate scarce financial resources to its firewalls rather than extending further help to Greece.

With the possibility of a Greece exit openly acknowledged, the outflow of deposits from the Greek banking system has accelerated. So far Greek banks have obtained liquidity by pledging collateral with the ECB or the Bank of Greece. If deposit outflows continued to accelerate, Greek banks would eventually run out of eligible assets. At that stage, either Greece would agree on a bank rescue operation with the Eurozone, or it would have to exit, as its banking system would end up being shut out of the Eurozone’s.

Economic consequences of a Greek exit

A Greek exit is in nobody’s interest. It would be devastating for Greece, which would find itself cut off from external funding. Devaluation would provide little solace, and the Greek people would face greater hardship than today (see also Xafa 2012 and Persaud 2012). The Eurozone would have to write off its exposure to Greece’s sovereign and banking system, but this would be a second order problem compared to the risk of contagion. Spreads on Spanish and Italian bonds have already been widening again, with Spain under special scrutiny, given heightened concerns on the state of its banking system.

Figure 2. Spain 10-year yields

Steps necessary to contain contagion from a Greek exit

The EU would have to act immediately.

- Even Germany would have to allow the unthinkable: an unconditional ECB commitment to provide unlimited liquidity to the Eurozone banking system and to act as a buyer of last resort – temporarily – for all remaining 16 Eurozone governments.

But the ECB cannot replace the ongoing process of fiscal and structural reforms. Monetary policy alone cannot ensure economic growth and debt sustainability.

Strong action by governments would be necessary to persuade markets that the ECB’s intervention would be both politically and economically sustainable. This should include:

- Accelerated ratification of the fiscal compact by all, and

- Agreement to put in place a common system of bank supervision and deposit insurance.

Additional EFSF/ESM funds could be mobilised as needed to offer further support to the weaker members; this should include the ability to recapitalise banking sectors in troubled countries. The ESM should be granted a banking license, which would allow them to obtain liquidity directly from the ECB, against collateral.

Spain’s situation shows clearly that a containment strategy has to convincingly address the banking sector as well. Banks and sovereigns have become even more mutually interdependent – both have to be buttressed at the same time.

Figure 3. Italy 10-year yields

Important progress has already been made

The fiscal compact has been agreed; Spain and Italy have already introduced debt-brake clauses in their constitutions, and Spain recently enacted new legislation to strengthen control over local public finances. Important structural reforms have already been launched or are under discussion.

Events might however unfold so fast that even a decisive European response would not prevent a temporary but severe dislocation to global financial markets. This would go hand in hand with a rise in global risk aversion, which could slow or reverse investment flows to emerging markets and dampen the already lacklustre US recovery. The risk of another temporary setback to the global recovery has increased.

References

Persaud, Avinash (2012) “Greek exit from the Eurozone: Neither inevitable nor desirable”, VoxEu.org, 30 May.

Xafa, Miranda (2012), “Greece’s exit from the Eurozone would be all pain, no gain”, VoxEU.org, 18 March.