Product standards are imposed to protect the health of domestic consumers. For a wide range of domestic and foreign products, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is responsible for ensuring the safety of these products in the US. While the FDA needs to prove a violation of product standards to deny market access for domestic products, it has the authority to refuse import shipments that “[only] appear to violate” a certain US product standard. This formulation in Section 801(a) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act leaves considerable room for discriminatory action of FDA officials with respect to imports.

Why are thousands of shipments blocked from entering the US market each year? According to the FDA, there are two main reasons for so-called import refusals. A product might be inferior or entail substantial health risk (adulteration) or a product might not meet the US labelling and certification requirements (misbranding). However, there is anecdotal evidence that the enforcement of product standards might also shield domestic industries from international competition. For instance, US catfish producers have lobbied for more frequent inspections of catfish imports to protect their industry (New York Times 2013).

Endogenous nature of protectionism

The endogenous nature of protectionism has been already stressed by Trefler (1993) and Essaji (2008) in two seminal papers on technical regulations. For a rich cross-section, Essaji (2008) assesses the impact of US technical regulations on US imports in the year 1999. His de jure measure for technical regulations does not vary across trading partners and does not seek to distinguish between trade increasing and reducing regulations. In contrast, this column sheds light on the economic effects of a de facto measure for technical regulations (import refusals) that varies over time and across country-product-groups (Grundke and Moser 2016). Import refusals capture any incidence of non-compliance with US product standards in a given country-product-group-year. The value of this variable increases, the more often existing technical regulations indeed bite.

Is protectionism countercyclical or not?

Bagwell and Staiger (2003) provide a theoretical model where trade policy becomes more protectionist in bad economic times. The more recent empirical evidence on this issue is mixed. On the one hand, based on a large panel dataset, Rose (2013) argues against countercyclical protectionism since World War II. On the other hand, Kee et al. (2013) find a relatively modest US trade policy reaction in antidumping. Furthermore, Bown and Crowley (2013) provide evidence that temporary trade barriers increase with negative macroeconomic shocks (e.g. a rise in the unemployment rate) in the US. Our paper differs from these insightful studies in an important dimension. There is no need to notify the stricter enforcement of product standards to the WTO.

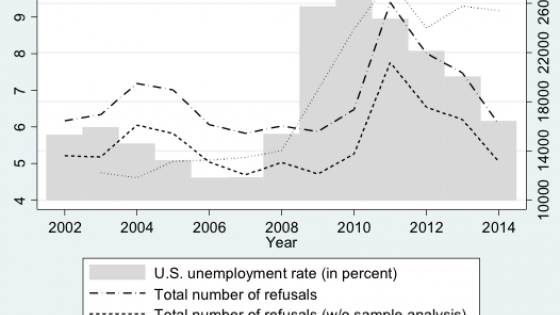

Figure 1 sheds some first light on stricter enforcement of US product standards during the Global Crisis and its aftermath. The total number of shipments inspected by the FDA roughly doubled from 2008 to 2011, before staying close to its peak in the years thereafter. These FDA-inspections include inspections with and without a product sample analysis. Note that, after a strong rise, the incidences of non-compliance with US product standards fell again hand in hand with the decreasing unemployment rate. This is even more remarkable if one considers that imports have resurged after the crisis. Another compelling fact is that import refusals without any product sample analysis dominate the evolution of total import refusals, whereby this type of refusals is arguably most prone to potential hidden protectionism.

Figure 1. US unemployment rate and hidden protectionism?

Source: Grundke and Moser (2016)

Non-compliance with US product standards is costly … for poorer countries

Our paper is based on a newly collected dataset. We carefully match information of the FDA’s Import Refusals Report database with disaggregated international trade data as provided by the US International Trade Commission. The empirical results are based on a bilateral gravity model for 93 imported product-groups from 170 exporters to the US for the years 2002 to 2014.

We find negative trade effects of import refusals that are confined to emerging and developing countries. A one standard deviation increase in refusals reduces short- and long-run exports from non-OECD countries to the US by $2.8 to $5 billion. Hence, non-compliance with US product standards implies substantial trade costs for poorer countries.

Our preferred specification of the Arellano Bond estimator proves to be robust in a number of dimensions, including the exact lag length of the internal instruments as well as the inclusion of an extensive set of fixed effects and additional external instruments that are based on information from EU’s Food and Feed Safety Alerts.

Is there evidence for hidden US protectionism?

Surprise, surprise – hidden actions are usually not directly observable. Zitzewitz (2012) states that agents prefer to keep a particular behaviour hidden if the behaviour in question is illegal or at least unethical. Hence, in the spirit of forensic economics, we look for (and are confident to find) unusual patterns in the data that are consistent with hidden protectionism.

- There is a strong rise in inspections and import refusals during those years with high unemployment rates.

- This increased number of blocked shipments is very unlikely to stem from a drop in quality (Levshenko et al. 2011).

- There is considerable leeway for FDA officers to enforce US product standards at the border and inspections without any sample analysis (i.e. without any scientific proof of violation) are driving the trade reducing effects.

- Since we control for legal changes in product standards, we are confident that stricter enforcement of product standards leads to the reduction in imports. This trade policy flies largely under the radar of international observers.

- We follow Fontagne et al. (2015) and look at the specific trade concerns that have been raised against the US within WTO’s committees. We confirm for the US the general perception of increased protectionism after the crisis as mentioned by Fontagne et al. (2015).

- Last but not least, our estimates provide indirect evidence that China and Russia are among those countries whose imports to the US fell most strongly due to import refusals during the crisis years while those from Ukraine fell least. Pure coincidence? Maybe, but the US-Russia-relations deteriorated to their lowest-point since the Cold War due to the Russia-Georgia conflict in August 2008 (Nichol, 2014).

Conclusions

Overall, we show that fear of protectionism during the economic crisis has not been unwarranted after all. The empirical evidence is in favour of a stricter enforcement of existing US product standards, in particular, vis-à-vis non-OECD countries. Notably, FDA import refusals without any product sample analysis are responsible for this negative effect on US imports during the Subprime Crisis and in its aftermath. We conclude that our empirical results are consistent with the existence of counter-cyclical, hidden protectionism due to non-tariff barriers to trade in the US. Hence, this paper corroborates worries raised by Baldwin and Evenett (2009) about a rise of murky protectionism.

Authors' note: The opinions expressed and arguments employed in this column are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the OECD or of the governments of its member countries.

References

Bagwell, K. and R. Staiger (2003), “Protection and the Business Cycle,” Advances in Economic Analysis and Policy, Vol. 3, No. 1, Art. 3, pp. 1-43.

Baldwin, R. and S. Evenett (2009), “The Collapse of Global Trade, Murky Protectionism, and the Crisis: Recommendations for the G20,” A VoxEU.org Publication.

Bown, C. and M. Crowley (2013), “Import Protection, Business Cycles, and Exchange Rates: Evidence from the Great Recession”, Journal of International Economics, Vol. 90, pp. 50–64.

Essaji, A. (2008), “Technical Regulations and Specialization in International Trade,” Journal of International Economics, No. 76, pp. 166-176.

Fontagne, L., G. Orefice, R. Piermartini and N. Rocha (2015), “Product Standards and Margins of Trade: Firm Level Evidence,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 97, pp. 29-44 .

Grundke, R. and C. Moser (2016), “Hidden Protectionism? Evidence from Non-tariff Barriers to Trade in the United States”, Working Papers in Economics and Finance, No. 2016-02, University of Salzburg.

Kee, H. L., C. Neagu and A. Nicita (2013), “Is Protectionism on the Rise? Assessing National Trade Policies During the Crisis of 2008,” Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 95, pp. 342-345.

Levchenko, A., L. Lewis and L. Tesar (2011), “The Great Trade Collapse of 2008-2009, The ‘Collapse in Quality’ Hypothesis,” American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings, Vol. 101, pp. 293-297.

Nichol, J. (2014), “Russian Political, Economic, and Security Issues and U.S. Interests,” Congressional Research Service, Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress, March 31, 2014.

Nixon, R. (2013), “Number of Catfish Inspectors Drives a Debate on Spending,” The New York Times, July 26th.

Rose, A. (2013), “The March of an Economic Idea? Protectionism Isn’t Countercyclic (anymore),” Economic Policy, Vol. 28, pp. 569-612.

Trefler, D. (1993), “Trade Liberalization and the Theory of Endogenous Protection: An Econometric Study of U.S. Import Policy,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 101, pp. 138- 160.

Zitzewitz, E. (2012), “Forensic Economics,” Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 50, pp. 731-369.