Editors’ note: This column first appeared in the Citi Research Global Economics Views series.

This column investigates the implications for the nominal exchange rate of a border tax adjustment (BTA) when there is BTA neutrality. A BTA means a change from origin-based taxation (exempting imports and taxing exports) to destination-based taxation (taxing imports and exempting exports). There is BTA neutrality when the real equilibrium (quantities, relative prices, measures of profitability and competitiveness, at home and abroad) of an open economy is unchanged when it moves from an origin-based to a destination-based value added tax (VAT) or cash-flow-based corporate profit tax (CPT).

The conventional wisdom on the exchange rate implications of a neutral BTA is that the currency of the country implementing the BTA will strengthen (appreciate) by a percentage equal to the VAT or CPT tax rate. The main insight of this column is that a weakening (depreciation) of that same magnitude is also possible. On the basis of the incomplete empirical information that is available, it is no more likely that the conditions that support an appreciation are satisfied than the conditions supporting a depreciation.1

BTA neutrality

In 1936, Abba P. Lerner wrote a remarkable paper (Lerner 1936) that demonstrated the equivalence of a given proportional tariff on imports and an equal proportional tax on exports.2 Like many powerful propositions, Lerner’s ‘symmetry’ or ‘equivalence’ result is both ex ante completely counter-intuitive and ex post (with a little reflection) completely obvious. Because trade is balanced (in a dynamic model not necessarily period-by-period but in present discounted value (PDV) terms), an import tariff and an equal proportional export tax discourage trade equally. With (PDV-)balanced trade, both the import tariff and the equal proportional export tax have to produce the same changes in incentives (relative prices faced by producers and consumers) in production, employment, and domestic and foreign demand in order to have the same effect on trade – exports and imports. There will be the same impact on the terms of trade (relative import and export prices).

Something very close to Lerner’s proposition that a tax (tariff) on imports has the same effect on the economy as a tax on exports also applies in a Keynesian world where trade is often not assumed to be PDV-balanced even in the long run. Consider a radical protectionist president of the US who simply bans all imports. Assume that ban is effective. What happens to the trade balance? Probably not much. The trade deficit could even increase.

The argument is simple.3 What happens to the income previously spent on imports? Assume it all gets spent on domestically produced goods and services instead – there is no reason why the import ban should, other things being equal, cause households to save more or corporations to invest less. If the economy is at full employment and domestic production cannot be increased, the diverted import demand absorbs goods and services that would previously have been exported. The trade balance is unchanged.

Assume instead that there are idle resources. Increased demand for domestic goods (from the diverted import demand) raises domestic output and employment. With a little help from the Keynesian multiplier, the increase in domestic output could be greater than the original boost to demand from the diverted import demand. However, increased output equals increased income. The part of it that is not taxed away or saved, raises consumption demand for domestic goods and services – goods and services that are therefore no longer available for exports. There is likely to be an increase in capital expenditure too, because import-competing sectors in the US are suddenly living in an economic nirwana. With tax revenues up, the local, state and federal governments are likely to boost their spending on goods and services.

The trade balance deficit will decline as a result of the ban on imports if and only if national saving (household, corporate and public) increases more than domestic capital expenditure (private and public) as a result of the ban on imports. A priori and empirically, this is no more plausible than the opposite outcome. So ‘Lerner symmetry’ is also relevant in a Keynesian world.

This ‘symmetry’ or ‘equivalence’ result has important implications for the economic effect of border tax adjustments. According to Lerner, a given proportional tariff (or tax) on imports is equivalent to an equal proportional tax on exports. The same logic implies that a given proportional reduction in tariffs on (or subsidy to or reduction in taxes on) imports is equivalent to an equal proportional reduction in taxes on (or subsidy to) exports. A given proportional tariff (or tax) on imports and an equal proportional subsidy to (or tax cut on) imports obviously cancel each other out: there is no effect on anything. But since a given proportional subsidy to (or reduction in tariffs on or reduction in tax on) imports is equivalent to the same proportional subsidy to (or reduction in taxes on) exports, it follows that imposing a given proportional tariff on imports and an equal proportional subsidy to exports (or removal of an equal proportional tax on exports) cancel each other out.

A BTA that moves an economy from an origin-based to a destination-based system of taxation therefore has no implications for competitiveness, import and export volumes, key relative prices, or sectoral profitability, at home or abroad. This is the neutrality or equivalence proposition for BTAs. Some of the classic references on the subject are Shibata (1967), Whalley (1979), Feldstein and Krugman (1990), De Meza et. al. (1994), Hufbauer and Gabyzon (1996) and Keen and Lahiri (1998).

Under origin-based taxation imports are exempted from the VAT and excluded from the CPT base, and exports are subject to the VAT and included in the CPT base. Under destination-based taxation, VAT is imposed on imports and imports are part of the CPT base, while exports are exempted from the VAT and export revenues are not part of the CPT base. A change from an origin-based CPT, that currently does not allow the immediate full expensing of capital expenditure, to a destination-based cash flow CPT (one that does in addition allow immediate full capital expenditure expensing) is under consideration in the US (see Ways and Means Committee 2016).

In this column we look at the (nominal) exchange rate implications of the neutrality proposition for BTAs, both for the case of a VAT and for the case of a cash flow CPT. The analysis for the cash flow CPT is the same as for the VAT, because of the well-known proposition (e.g. Auerbach et al. 2017), that the introduction of a broad-based uniform rate cash flow CPT is equivalent to the introduction of a broad-based, uniform rate VAT at that same uniform rate, together with a reduction in payroll tax rates by that same rate.4

BTA neutrality and the nominal exchange rate

The formal theory of BTA is for barter economies – all propositions involve real quantities and relative prices only. The two key ‘real’ implications of BTA neutrality are the following:

- The tax-inclusive relative price of imports to exports rises by a percentage equal to the tax rate.

- The tax-exclusive relative price of imports to exports falls by a percentage equal to the tax rate.5

The theory has no implications for the nominal exchange rate. Despite this, there is a widespread belief, expressed mostly in media interviews, op-eds, and other non-technical writings, that BTA neutrality is achieved through an appreciation of the nominal exchange rate of the country implementing the BTA, by a percentage equal to the tax rate. Examples are Auerbach and Holtz–Eakin (2016), Worstall (2017), Feldstein (2017), Irwin (2017), Krugman (2017), Davies (2017), Greenberg and Hodge (2017), Setzer (2017), Summers (2017) and, as part of an earlier debate on VAT, Mankiw (2010). So if the US were (1) to cut the current corporate tax rate (in the currently origin-based US system of corporate taxation) from 35% to 20%, (2) to change to a cash flow tax (by making capital expenditure outlays fully deductible when they are made), and (3) to move to a destination-based cash flow corporate profit tax, the third step (the BTA) would strengthen the external value of the US dollar by 20%. This has created a lot of interest in BTAs even among those who are not engaged in cross-border trade in real goods and services. Those engaged in cross-border financial investment are clearly interested in the possibility of a 20% further appreciation of the US dollar, how much of this potential future dollar appreciation is already ‘priced in’, and so on. This column is likely to add to the uncertainty about the response of the dollar to a BTA in the US.

To get from the real implications of BTA neutrality – the two just-stated propositions about the terms of trade – to the implications of BTA neutrality for the nominal exchange rate, we need assumptions about the constancy of certain nominal prices. Constancy of nominal prices can be interpreted by those of a Keynesian persuasion as (short-run) nominal rigidity or stickiness of nominal prices, but can also be interpreted by those of a New Classical persuasion as nominal constancy through appropriate domestic and foreign monetary and exchange rate policies, despite complete nominal price flexibility. In what follows, I choose the Keynesian characterisation, which has the expositional advantage of making it unnecessary to characterise a complete global monetary economy and the domestic and foreign monetary and exchange rate policies supporting alternative nominal price constancy assumptions.

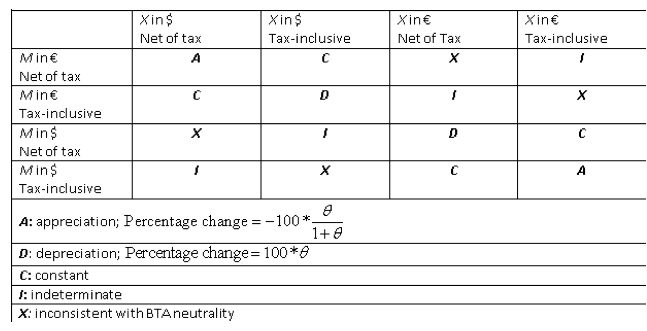

In an open economy with taxes, constancy of nominal prices has two dimensions: (1) the currency in terms of which prices are constant (home currency (dollar), or foreign currency (euro)), and (2) whether it is tax-inclusive or tax-exclusive prices that are constant in nominal terms. There are 16 constant nominal price combinations to consider, as shown in Figure 1. Figure 1 also contains the implications of the various constant nominal price assumptions for the nominal dollar exchange rate. The derivation of these results can be found in a longer and more technical version of this column (Buiter 2017).

In Figure 1, M stands for imports, X for exports and e for the nominal dollar exchange rate (number of dollars per euro). A fall in e is an appreciation (strengthening) of the dollar and an increase in e a depreciation (weakening) of the dollar.

Figure 1. Nominal dollar exchange rate response to BTA under neutrality

Source: Citi Research

Of the 16 possible nominal price constancy configurations, two produce a dollar appreciation and two a dollar depreciation. Four support a constant exchange rate, four generate indeterminacy of the nominal exchange rate, and four are inconsistent with neutrality.

Fortunately, it is only necessary to consider four cases in greater detail. The four indeterminate nominal exchange rate outcomes and the four nominal price constancy assumptions that are incompatible with BTA neutrality are of no interest. The four constant nominal exchange rate outcomes all have the undesirable characteristic that the nominal price constancy assumptions that produce these outcomes either have import prices constant net-of-tax but export prices constant including tax, or import prices constant including tax but export prices constant net-of-tax. This asymmetry is not easily rationalised and we will ignore the four constant nominal exchange rate outcomes for that reason.

What’s with the tax-inclusive versus net-of-tax pricing?

The issue of whether nominal prices are constant (temporarily sticky or rigid) net-of-tax or including tax may seem esoteric and mostly likely irrelevant. It is not. It can make the difference between a 20% depreciation or a 20% appreciation of the dollar if there is BTA neutrality (assuming the US engages in a BTA for the corporate profit tax with an across-the board CPT rate of 20%). The following example makes this clear.

Consider the case where US import prices are constant/sticky in dollars (pricing-to-market) net of tax, and US export prices are constant/sticky in euros net of tax. In that case, a BTA (imports that were exempt from taxation before are now taxed at 20%) means that the tax-inclusive price of US imports in dollars goes up by 20%. BTA neutrality implies that in this case the dollar depreciates by 20%, meaning that the tax-inclusive price of US imports in euro (the foreign currency) is constant. Of course, the net-of-tax price of US imports in euros (relevant to the profits of the Eurozone exporter to the US) falls by 20%. BTA neutrality is preserved by an increase in the US dollar price of US production for the US market by 20%, an increase in US dollar wages of 20% and an increase in the net-of-tax US export price in dollars by 20%. The tax-inclusive US export price in dollars is constant (exports are no longer taxed), and the tax-inclusive US export price in euros falls by 20%. So BTA neutrality requires Eurozone nominal wages (in euros) and the price of Eurozone goods produced for the Eurozone market to fall by 20%.

Now maintain the assumption of pricing-to-market for US imports (import prices are constant/sticky in dollars) and US exports (export prices stick/constant in euros), but assume that it is tax-inclusive dollar prices of imports and tax-inclusive euro prices of exports that are constant.

In this case, a BTA means that the net-of-tax price of US imports in dollars falls by 20% - because imports now are taxed at a 20% rate. BTA neutrality implies that in this case the dollar appreciates by 20%, so the net-of-tax price of US imports in euros is constant. The tax-inclusive price of US imports in euros rises by 20%. BTA neutrality is preserved by a constant US dollar price of US production for the US market and a constant US dollar wage. The tax-inclusive US export price in euros is constant by assumption. Since exports are no longer taxed, the net-of-tax US export price in euros rises by 20%. Because of the dollar appreciation, the net-of-tax US export prices in dollars is constant. BTA neutrality requires Eurozone nominal wages (in euro) and the price of Eurozone goods produced for the Eurozone market to be constant.

Exchange rate appreciation

The ‘Keynesian’ case with net-of-tax prices constant

Exchange rate appreciation occurs under a neutral BTA when nominal import and export prices are constant net of tax and import prices (net of tax) are constant in foreign currency (euro) and export prices are constant in domestic currency (dollar). This ‘origin currency pricing’ is the assumption made in most intermediate macroeconomics textbooks with a Keynesian flavour, although these models don’t consider the net-of-tax versus tax-inclusive pricing issue.

In this case, with the net-of-tax price of US exports constant in dollars, the BTA results in a decline in the tax-inclusive price of exports in dollars, by the same percentage as the tax rate. The appreciation of the dollar by that same percentage means that the tax-inclusive price of exports in euros is unaffected by the BTA.

With the net-of-tax price of US imports constant in euros, the tax-inclusive price of imports in euros rises by the same percentage as the tax rate. The appreciation of the dollar by that same percentage means that the tax-inclusive price of imports in dollars is unchanged.

The dollar price of US goods produced for the domestic market and US wages, in dollars, remain unchanged. The foreign currency price of foreign goods produced for the foreign market remains unchanged and does the foreign money wage in euros.

Note that the tax-inclusive relative price of imports to exports rises by the same percentage as the tax rate and that the net-of-tax relative price of imports to exports falls by the same percentage as the tax rate.

Pricing-to-market with tax-inclusive prices constant

Exchange rate appreciation also occurs under a neutral BTA if tax-inclusive prices are constant and the (tax-inclusive) price of US imports is constant in dollars and the (tax-inclusive price) of US exports is constant in euros. This ‘destination currency pricing’ has considerable empirical support, although, again, the issue of tax-inclusive versus net-of-tax pricing is not considered in this literature.

In this case, with the tax-inclusive price of US exports constant in euros, the net-of-tax euro price of exports rises by the same percentage as the tax rate when the BTA occurs. The appreciation of the dollar by that same percentage means that the net-of-tax dollar price of exports is constant and that the tax-inclusive dollar price of exports falls by the same percentage as the tax rate.

With the tax-inclusive price of US imports constant in dollars, the BTA causes the net-of-tax dollar price of US imports to fall by the same percentage as the tax rate. The appreciation of the dollar means that the net-of-tax euro price of US imports is constant. The tax-inclusive euro price of US imports rises by the same percentage as the tax rate. The dollar price of US goods produced for the US market, the US money wage in dollars, the euro price of foreign goods produced for the foreign market, and the foreign money wage in euros remain constant.

Again, the tax-inclusive relative price of imports to exports rises by the same percentage as the tax rate and the net-of-tax relative price of imports to exports falls by the same percentage as the tax rate.

Exchange rate depreciation

The ‘Keynesian’ case with tax-inclusive prices constant

Exchange rate depreciation occurs under a neutral BTA when tax-inclusive prices are constant and (tax-inclusive) US export prices are constant in dollars and (tax-inclusive) US import prices are constant in euros.

With tax-inclusive US export prices constant in dollars, net-of-tax US export prices (in dollars) rise by the same percentage as the tax rate as a result of the BTA. The dollar depreciates by the same percentage as the tax rate, so the net-of-tax euro price of US exports remains constant and the tax-inclusive euro price of US exports falls by the same percentage as the tax rate.

With the tax-inclusive euro price of US imports constant, the net-of tax euro price of US imports falls by the same percentage as the tax rate. Because of the dollar depreciation, the tax-inclusive dollar price of US imports rises by the same percentage as the tax rate and the net-of-tax dollar price of US imports is constant.

The dollar price of US goods produced for the domestic market and the US money wage in dollars rise by the same percentage as the tax rate. The euro price of foreign goods produced for the foreign market falls by the same percentage as the tax rate and so does the foreign money wage in euros.

Again, the tax-inclusive relative price of imports to exports rises by the same percentage as the tax rate and that the net-of-tax relative price of imports to exports falls by the same percentage as the tax rate.

Pricing-to-market with net-of-tax prices constant

Exchange rate depreciation also occurs under a neutral BTA when net-of-tax prices are constant and (net-of-tax) US export prices are constant in euros and (net-of-tax) US import prices are constant in dollars.

With net-of-tax US export prices constant in euros, tax-inclusive US export prices in euros fall by the same percentage as the tax rate. The dollar depreciates by the same percentage as the tax rate, so the tax-inclusive US export price in dollars is constant and the net-of-tax US export price in dollars rises by the same percentage as the tax rate.

With net-of-tax US import prices constant in dollars, tax-inclusive US import prices in dollars rise by the same percentage as the tax rate. With the dollar depreciating by that same percentage, the net-of-tax US import price in euros falls by the same percentage as the tax rate and the tax-inclusive US import price in euros is constant.

The dollar price of US goods produced for the domestic market and the US money wage in dollars rise by the same percentage as the tax rate. The euro price of foreign goods produced for the foreign market falls by the same percentage as the tax rate, and so does the foreign money wage in euros.

Again, the tax-inclusive relative price of imports to exports rises by the same percentage as the tax rate, and the net-of-tax relative price of imports to exports falls by the same percentage as the tax rate.

Which nominal price constancy assumptions are the most plausible?

Anyone with a Keynesian view of nominal wage and price rigidities will be comfortable with the dollar appreciation scenarios but not with the dollar depreciation scenarios. The reason is that in the dollar appreciation scenarios the dollar price of US domestic goods produced for the US market and the US money wage (in dollars) remain constant and so do the euro price of foreign goods produced for the foreign market and the foreign money wage in euro – consistent with the Keynesian view on the prevalence of nominal wage and price rigidities.

In the depreciation scenarios, the dollar price of US goods produced for the US market and the US money wage in dollars rise by the same percentage as the tax rate. The euro price of foreign goods produced for the foreign market and the foreign money wage in euros fall by the same percentage as the tax rate. This would not be possible in a Keynesian world with nominal wage and price rigidities. From a Keynesian perspective, therefore, the depreciation scenarios are therefore inconsistent and must be rejected, leaving just the two appreciation scenarios.

This is not conclusive, however, as the Keynesian views on nominal wage and price rigidities are not universally held by members of the economics profession. It therefore makes sense to look for direct empirical evidence on pricing-to-market, or destination currency pricing, versus origin currency pricing, and on tax-inclusive versus net-of-tax pricing.

Pricing-to-market

The pricing-to-market paradigm was created by Paul Krugman (1986), and a large number of empirical studies have tested it. Examples include, apart from Krugman (1986), Marston (1989), Blinder et. al. (1998), FitzGerald and Shortall (1998), Gil-Pareja (2003), Warmedinger (2004), Fitzgerald and Haller (2011), Asprilla et. al. (2015)

A typical example of the empirical findings is Gil‐Pareja (2002), whose study of pricing-to-market in European car markets during 1993 and 1998 found that, for imported cars, price stability in terms of the local currency is a strong and pervasive phenomenon. Interestingly, this ‘destination currency’ price stability (or stickiness) was independent of the invoicing currency, which in many case with the origin currency. Most other empirical studies find robust evidence of pricing-to-market, but the strength of the phenomenon varies between countries, sectors, industries and even firms, as well as over time. We consider pricing-to-market to be the best simple characterisation of the pricing behaviour of exporters in their export markets, but at the same time recognise that the fit is far from perfect and, for certain products and countries, downright poor.

Tax-inclusive versus net-of-tax pricing

Much to our surprise, we have not been able to find any empirical studies that directly address this issue. Most empirical studies studying wage setting at the micro level don’t mention the word ‘tax’ (e.g. Heckel et. al. 2008). In the literature on the incidence of taxes (trying to distinguish who pays a tax (from whom the tax is collected) from who bears that tax after allowing for the general equilibrium effects of the tax on wages, prices, capital accumulation, etc.), evidence is cited (e.g. Dye 1984) that a payroll tax levied on the workers directly reduces the after-tax money wage of the worker, without any necessary effect on the wage including the payroll tax. In this case, there is no effect on the nominal prices set by firms: the reduction in the after-tax money wage is the same, proportionally, as the reduction in the after-tax real wage. When the payroll tax is instead levied on the employer, the worker’s nominal wage does not change but there tends to be an increase in the nominal price of the products produced and sold by the firm. The worker still pays the tax in full, when the supply of labour is inelastic, in the sense that the real wage falls by a percentage equal to the tax rate, but this occurs through an increase in the general price level, including the cost of the consumption bundle of the worker, by a percentage equal to the employer’s payroll tax rate.

This phenomenon, even if it is indeed empirically robust, does not resolve the question of whether constant net-of-tax pricing or constant tax-inclusive pricing is the norm. In the case of the payroll tax paid by the worker, the example just cited has tax-inclusive constant nominal wages. In the case of the payroll tax paid by the employer, there are net-of-tax constant nominal output prices. The range of views on the mechanisms through which workers ultimately bear (part of) the cost of any payroll tax is exemplified by contrasting the view that a payroll tax paid by employers will reduce workers’ real wages through higher prices and unchanged money wages with the view held by the CBO that “… employers’ share of payroll taxes is passed on to employees in the form of lower wages than would otherwise be paid”6 (see also OECD 1990 and Ebrahimi and Vaillancourt 2016).

Conclusion

This column addresses the question of what happens to the nominal exchange rate when there is a border tax adjustment and this BTA is neutral. The answer is: we don’t know. Of the nominal pricing assumption combinations that support the four interesting cases, two conclude that the currency will strengthen, or appreciate, by the same percentage as the tax rate; typically a tax rate of 20% is used in US discussions, because this is widely judged to be a reasonable forecast of the future corporate profit tax rate in the US. Two other sets of nominal pricing assumptions support a weakening or depreciation of the currency by the same percentage as the tax rate.

Personally, I would definitely opt for the pricing-to-market/destination currency pricing assumption (US import prices are constant in dollars and US export prices are constant in euro) and probably the constant net-of-tax pricing assumption. That would produce the depreciation outcome. Anyone who firmly holds the view that origin currency pricing rules the roost (US export prices are constant in dollars and US import prices are constant in euros) will get the appreciation outcome if nominal prices are assumed to be constant net of tax. Origin currency pricing with constant tax-inclusive nominal prices would yield the depreciation outcome.

Empirical evidence weakly supports pricing-to-market. There is no evidence on tax-inclusive versus net-of-tax pricing.

The uncertainty facing anyone trying to figure out the impact of a BTA on the dollar is even greater than indicated in the previous three paragraphs. Throughout this column, the maintained assumption has been that BTA neutrality holds. That, of course, is a contested empirical matter.

As regards BTAs involving a cash flow corporate profit tax, there is no history to inform us and no data. As regards BTAs involving a VAT, we have a number of historical experiments, most notably the introduction of a destination-based VAT in the EU. An extensive empirical evaluation of the EU record (Institute for Fiscal Studies 2011) offers qualified support for the neutrality hypothesis. Econometric estimation of the degree to which the historical experience was consistent with BTA neutrality does, of course, rely on a large number of untested and generally untestable identifying assumptions. The estimated ‘degree of neutrality’ varies across countries and sectors (see also Desai and Hines 2005, Benedek et. al. 2016 and Liu and Lockwood 2016).

A further unavoidable complication is that real-world VATs are not the universal uniform tax rate for all goods and services. There are multiple VAT rates, exemptions, and zero ratings. The same will undoubtedly be the case should the US implement a BTA for its corporate profit tax. Widespread lack of faith in the BTA neutrality proposition will lead importers to plead for reduced rates or exemptions. So even if all other assumptions necessary to produce BTA neutrality were satisfied, the fact that we are bound to have a very poor approximation to a true BTA means that there will be no neutrality.

Finally, even if the US were to implement an ideal-type corporate profit tax BTA and even if all the conditions for BTA neutrality were satisfied, there are many other factors influencing the nominal and real exchange rates of the dollar: fiscal policy (including anticipated future fiscal policy) at home and abroad, monetary policy (including anticipated future monetary policy) at home and abroad, changes in risk aversion, changes in risk perceptions, capital controls and foreign exchange controls, fear of sovereign default, fear of a currency union break-up etc.

Many of these factors are unobservable and they are likely to change frequently and significantly. So even if there were certainty that a possible future US corporate profit tax BTA would be completely neutral, and even if a currency investor were fully confident about the sign and magnitude of the response of the dollar exchange rate, should a BTA occur, it would be very difficult to determine how much of the BTA neutrality-driven exchange rate appreciation or depreciation has already been priced into spot, forward, and options markets for the dollar and other currencies.

So, in the spirit of Socrates, we have to say about the exchange rate implications of a BTA: I know I know nothing, but at least I know that. The main lesson of this column is that it would be unwise to think of the exchange rate effect of a corporate profit tax BTA as a one-way bet that the US dollar will strengthen. Not only do we not know the magnitude of the exchange rate effect of a BTA, we don’t even know the sign or direction.

References

Asprilla, A, N Berman, O Cadot and M Jaud (2015), “Pricing-to-market, Trade Policy, and Market Power”, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, International Economics Department, Working Paper Series, Working Paper N IHEIDWP04-2015.

Benedek, D, R de Mooij, M Keen and P Wingender (2016), “Estimating VAT Pass Through,” IMF Working Paper 15/214.

Blinder, A, E Canetti, D Lebow and J Rudd (1998), Asking About Prices: A New Approach to Understanding Price Stickiness, New York, Russell Sage Foundation.

Buiter, W H (2017), “Exchange Rate Consequences of Border Tax Adjustment Neutrality”, Working Paper, forthcoming February.

Davies, G (2017), “The worrying macro-economics of US border taxes", Financial Times, Comment, Blogs, 15 January,

De Meza, D, B Lockwood, and G D Myles, (1994), “When are origin and destination regimes equivalent?” International Tax and Public Finance 1: 5-24.

Desai, M A and J R Hines, Jr. (2005), “Value –Added Taxes and International Trade: The Evidence”, January.

Dye, R F (1984), “Evidence on the Effects of Payroll Tax Changes on Wage Growth and Price Inflation: A Review and Reconciliation”, Social Security Administration, Office of Research and Statistics, ORES Working Paper Series Number 34.

Ebrahimi, P and F Vaillancourt (2016), "The Effect of Corporate Income and Payroll Taxes on the Wages of Canadian Workers:, Fraser Institute, January.

Feldstein, M S and P R Krugman (1990), “International Trade Effects of Value-Added Taxation”, pp. 263 – 282, in A Razin and J Slemrod (eds). Taxation in the Global Economy, University of Chicago Press.

Feldstein, M S (2017), “The House GOP’s Good Tax Trade-Off; Exempting exports from corporate income taxes would strengthen the dollar and raise revenue.” Wall Street Journal, Opinion, Commentary, January 5.

Fitzgerald, D and S Haller (2011), “Pricing-to-Market: Evidence From Plant-Level Prices”, Working Paper, December.

Fitzgerald, J and F Shortall (1998), “Pricing to Market, Exchange Rate Changes and the Transmission of Inflation” The Economic and Social Review 29(4)4: 323-340, October 1998

Gil Pareja, S (2003).“Pricing to market behaviour in European car markets”, European Economic Review 47(6): 945‐962

Greenberg, S and S A Hodge (2017), “FAQs about the Border Adjustment”, 20 January.

Heckel, T, H Le Bihan and J Montornès (2008), “Sticky wages; evidence from quarterly microeconomic data”, ECB Working Paper Series, No 893, May.

Institute for Fiscal Studies (2011), A retrospective evaluation of elements of the EU VAT system; Final report, TAXUD/2010/DE/328, TAXUD/2010/DE/328, FWC No. TAXUD/2010/CC/104, London, December 1.

Irwin, N (2017), “A Tax Overhaul Would be Great in Theory. Here’s Why It’s So Hard in Practice”, New York Times, The Upshot, Economic View, February 10.

Krugman, P (1986), “Pricing to market when the exchange rate changes”, in: S. W. Arndt and J.D. Richardson (Eds.), Real‐financial Linkages among Open Economies. MIT Press, Cambridge.

Krugman, P (2017), “Border Tax Two-Step (Wonkish)”, New York Times, Opinion Pages, The Conscience of A Liberal, January 27, 2017.

Lerner, A P (1936), "The Symmetry Between Import and Export Taxes", Economica, N.S., 3(11), pp. 306–313.

Liu, L and B Lockwood (2016) “VAT notches, voluntary registration and bunching: Theory and UK evidence”, Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation Working Paper 16/10

Mankiw, G (2010), “Is a VAT good for exports”, Greg Mankiw’s Blog, May 18.

Marston, R. C (1989) “Pricing to Market in Japanese Manufacturing”, Journal of International Economics, 29(3), PP 217‐236.

OECD (1990), “Employer versus employee taxation: the impact on employment”, Chapter 6 in the Employment Outlook 1990.

Ray, E J (1975), “The Impact of Monopoly Pricing on the Lerner Symmetry Theorem”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 89(4), pp. 591-602, November

Setzer, B (2017), “How Serious Is the Threat to Global Financial Stability From a Border-Adjustment Tax?”, Council on Foreign Relations, Follow the Money Blog, February 14.

Shibata, H (1967) “The theory of economic unions: A comparative analysis of customs unions, free trade areas, and tax unions” in: C.S. Shoup, ed., Fiscal harmonization in common markets, vol. I, Theory, Columbia University Press, New York.

Endnotes

[1] There is a little verbal sloppiness here which, however, saves a lot of additional words or notation. Strictly speaking, if the tax rate is θ, in the case where the currency depreciates, the domestic currency price of foreign exchange rises by a percentage equal to 100*θ. In the case where the currency appreciates, the domestic currency price of foreign exchange changes by a percentage equal to -100*θ/(1+θ). So, with a 20% corporate profit tax rate, in the depreciation case the domestic currency price of foreign currency rises by 20%. In the appreciation case, the domestic currency price of foreign currency falls by 16.7%.

[2] The conditions for which Lerner proved the ‘symmetry’ result included competitive markets, constant returns to scale and balanced trade. It generalises to imperfectly competitive markets also (see Ray 1975).

[3] I ignore the adverse supply-side impact of vanishing imports of raw materials, intermediate inputs and capital goods. Alternatively, the import ban could be restricted to consumer goods and services.

[4] Strictly speaking, the equivalence of a given percentage rate destination-based cash flow CPT and the same percentage rate destination-based VAT requires that in the VAT case there be a cut in the tax on all domestically sourced inputs into production by that same percentage rate. Not only the payroll tax should be cut, but also taxes on rents and other domestic costs, including interest etc.

[5] As in footnote 1, strictly speaking, if the tax rate is θ, the tax-inclusive relative price of imports to exports changes (rises) by a percentage equal to 100*θ and the tax-exclusive relative price of imports to exports changes (falls) by a percentage equal to -100*θ/(1+θ).

[6] “CBO’s analysis of effective tax rates assumes that households bear the burden of the taxes that they pay directly, such as individual income taxes and employees’ share of payroll taxes. CBO assumes—as do most economists—that employers’ share of payroll taxes is passed on to employees in the form of lower wages than would otherwise be paid. Therefore, the amount of those taxes is included in employees’ income, and the taxes are counted as part of employees’ tax burden.” http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/EffectiveTaxRates2006.pdf, page 3.