Developed countries have seen well-documented increases in the number of mothers returning to work after having children (Eckstein and Lifshitz 2011, Fogli and Veldkamp 2011). More recently, there has been also an increase in the number of hours worked by mothers. For example, in Norway between 1986 and 2010, the proportion of mothers working full-time rose from 60% to 76% for mothers with a degree and from 42% to 60% for mothers with compulsory schooling.

What may be driving these changes are factors such as the availability of childcare, cultural changes, or more general policy changes to promote mothers’ labour supply. But in addition, a propagating mechanism that can amplify the effect of these triggering events is the influence of peers on individual labour supply decisions. A large peer effect may well explain the trend for mothers to work longer hours when they return after having a child.

In a recent paper, we establish that the example set within families (her sisters and female cousins) has a major role in deciding the hours women will consider after returning from maternity leave (Nicoletti et al. 2017).

We are all used to the idea that, almost subconsciously, our family establish precedents in our lives. We find ourselves repeating the admonishments of our parents to our own children, for example – we fall into step with the fashions of our social groups. It is now clearer how dramatic this effect can be on those mothers planning for a post-baby job.

We analysed data from more than 45,000 new mothers in Norway between 1997 and 2002. This allowed an examination of how new mothers decide the number of hours to work in the first seven years after having a child.

There are difficulties in estimating the peer effect of family’s decisions on a mothers’ decisions, which we take steps to overcome. The paper describes in detail each issue and our solution, and we focus now on one particular concern, which is the reflection problem.

In a simple estimation of our family peer effect, the reflection problem makes it impossible to differentiate the effect of a mother’s family on her decisions, from the effect of the mother on her family’s decisions (Manski 1993). This bias can be overcome by finding exogenous variation in the family’s choices. We create this variation by exploiting changes in the family’s behaviour that comes solely from the family’s neighbour’s actions and decisions. This is an application of the partially overlapping peer groups method (Bramoullé et al. 2009, Lee et al. 2010). The identification assumption is satisfied as long as the family’s neighbours do not interact meaningfully with the mother herself.

We consider whether this assumption may fail to hold in specific contexts. For example, the most obvious way a mother can be influenced by her family’s neighbours is if the mother lives in the same neighbourhood as her family or if a mother works in the same labour market or workplace as her family’s neighbours. We provide empirical evidence that this, as well as other threats to the validity of our identification strategy, do not bias our estimation.

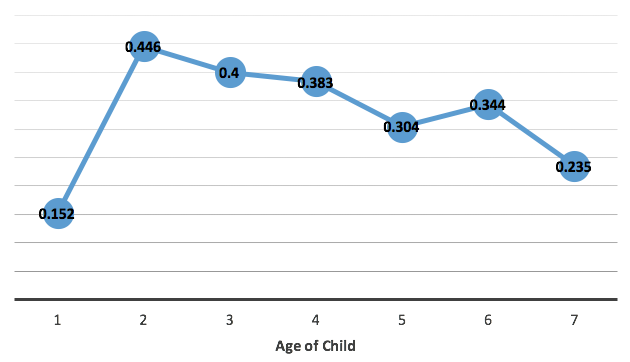

Figure 1 displays the results which show that there is a very small peer effect one year after birth, when mothers are entitled to paid parental leave. After this, the biggest effect of the family on new mothers’ labour supply decisions is in the pre-school years. During that time, an increase of one hour in the time worked per week by a woman’s sisters and female cousins after childbirth corresponds to an increase of up to 30 minutes in the weekly hours that a new mother will work.

Figure 1 Family peer effect on mothers’ hours worked

To understand what this means, imagine two identical women who have the same work experience, have children at the same time, and have the same education. If their sisters work very similar hours after having children, then they are likely to choose the same number of hours to work after returning from maternity leave. However, if a policy leads to an increase in the average hours worked by one mother’s sisters by, say, 10 hours, then this mother will work up to five hours more than the other, through the peer effect alone.

Before children are at school, which in Norway is at the age of six, the mother faces a balancing act: work to earn money but use costly childcare, or save on childcare and spend time with her child. Once the child starts school this trade-off is less important because earning income can coincide with the school day, and this is what the results show.

So how does her family influence the mother’s decisions? First, she might simply conform to the established family norms. Second, new mothers may find in their family a resource for information about the effect of working on their children.

In particular, mums may seek reassurances about the effect that returning to work will have on their children from close relatives who have already been through something similar. That might be anything from practical knowledge about childcare availability, to understanding how well children cope with the mother’s absence.

The research also asked why a mother might be swayed by her family’s choices of working hours in the years soon after having children. The findings are that it is the hours worked by her family rather than family’s earnings that influence the mother working decisions from the end of maternity leave eligibility up to the final pre-school years. Mothers start to be motivated by the money their family earns only from the child’s age being four upwards.

Why is this? Previous research has shown that the time mums spend with their children is highest for newborns and falls as children age (Del Boca et al. 2012, Guryan et al. 2008, Zick and Bryant 1996), while the money spent on children starts off quite low and increases as they grow up (Kornrich and Furstenberg 2013).

And so the money earned by the family starts to influence decisions during the later pre-school years when more is spent on their children. Of course, it may be that mothers are interested in the earnings of their family simply in order to keep pace with established patterns of spending. If her family goes on a holiday, the mother might choose to work more hours to buy a holiday herself.

What is clear from the new research is that public policy changes can create a social multiplier effect. This means that any policy aimed at raising participation of mothers in the workforce by a single hour per week will actually raise labour supply of not just the targeted mothers but also of her family. The peer effect we have shown, where one hour extra translates into an extra 30 minutes for fellow women in her family, creates a cascade effect.

Other peer groups may also have an important influence on mothers. Our research finds that choices made by neighbourhood friends will influence mothers, even if it is to a lesser degree than her family. An increase of an hour a week worked by neighbours will lead to an increase in the mother’s hours by between 2 and 17 minutes in the three to five years after having a child.

We know that many policies are enacted to encourage mothers back to work, including tax credits for example. To estimate the total effect of such policies on the labour supply of mothers, it is important to include the social multiplier effect, which means that mothers not directly targeted by the policy will be also affected by it.

References

Bramoullé, Y, H Djebbari, and B Fortin (2009), “Identification of Peer Effects Through Social Networks”, Journal of Econometrics, 150: 41-55.

Del Boca, D, M Monfardini, and C Nicoletti (2012), “Children's and Parents' Time-Use Choices and Cognitive Development during Adolescence”, Working Paper 2012-006, Human Capital and Economic Opportunity Working Group.

Eckstein, Z, and O Lifshitz (2011), “Dynamic Female Labour Supply”, Econometrica, 79(6): 1675-1726.

Fogli, A, and L Veldkamp (2011), “Nature or Nurture? Learning and the Geography of Female Labour Force Participation”, Econometrica, 79 (4): 1103-1138.

Guryan, J, H Hurst, and M Kearney (2008), “Parental education and parental time with children”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(3): 23-46.

Kornrich, S, and F Furstrenberg (2013), “Investing in children: Changes in parental spending on children, 1972-2007”, Demography, 50: 1-23.

Manski, C (1993), “Identification of Endogenous Social Effects: The Reflection Problem”, Review of Economic Studies, 60: 531-42.

Nicoletti, C, K Salvanes, and E Tominey (2017), “The Family Peer Effect on Mothers’ Labour Supply”, White Rose Research Online.

Zick, C D, and W K Bryant (1996), “A New Look at Parents' Time Spent in Child Care: Primary and Secondary Time Use”, Social Science Research, 25: 260-280.