The 20th century has been characterised by Fordism and large conglomerates, an era in which the traditional paradigm of large firms as the most productive and paying the highest wages would strongly hold. In this context, it should come as no surprise that the link between firm productivity, firm size and wages has been the subject of many economic studies, both from a theoretical and empirical point of view. The literature typically finds that:

- workers at large employers get higher wages on average – the ‘size-wage premium’ (Moore 1911); and

- large employers are on average more productive than smaller ones – what we call the ‘size-productivity premium’.

But the majority of these studies focus exclusively on manufacturing in a single country; often because of lack of data, services are rarely analysed. With manufacturing representing only around 15% of total value added and employment in OECD economies (and decreasing), it is vitally important to understand whether the existing predictions apply to the service sector.

In a new study (Berlingieri et al. 2018a), we provide systematic cross-country evidence on the link between size, productivity, and wages thanks to a novel micro-aggregated firm-level dataset for the period 1994-2012 from 17 countries: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, and Switzerland.

The dataset contains harmonised information on productivity, wages, and firm size. Unlike previous studies, it (1) uses data that are based either on the full population of firms in each country or a representative re-weighted sample thanks to information from business registers, (2) covers manufacturing and services in 25 countries, and (3) measures wage, labour productivity, and multi-factor productivity (MFP) across size classes (for details, see Berlingieri et al. 2017). Here we focus exclusively on 17 countries for which information on firm size is available, and for both manufacturing and non-financial market services.

A paradigm shift in today's service economy

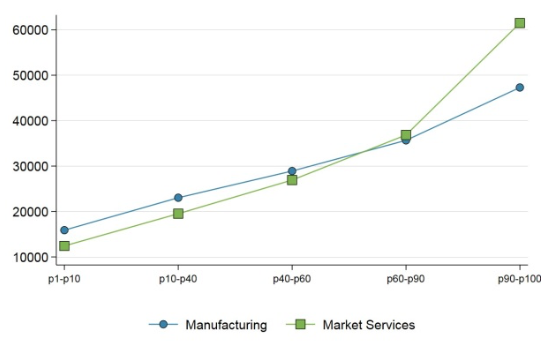

The key fact unveiled in the study can be illustrated by simply plotting the (weighted) cross-country average of wages and labour productivity by eight size classes for manufacturing and market services separately.

Figure 1 shows that, while in manufacturing both productivity and wages increase significantly with firm size, this relationship does not hold for services. Both labour productivity and wages exhibit a distribution over size classes that is flatter in services than in manufacturing. In contrast, wages increase with productivity in both manufacturing and especially non-financial market services (see panels C and D).

Figure 1 Averages by size classes and productivity quantiles

Panel A: Wages by size classes

Panel B: Labour productivity by size classes

Panel C: Wages by labour productivity quantiles

Panel D: Wages by multi-factor productivity quantiles

Note: Countries included: AUS, AUT, BEL, CAN, CHE, CHL, DEU, DNK, FIN, FRA, HUN, ITA, JPN, NLD, NOR, PRT, SWE. Figures 1a and 1b are weighted averages over 8 size classes: very micro (less than 5 employees), micro (5-9), small (10-19), medium-small (20-49), medium-large (100-249), large (250-499), very large (more than 500). Figures 1c and 1d are weighted averages over 5 bins of theproductivity distribution: 1st to 10th percentile,10th to 40th, 40th to 60th, 60th to 90th, and 90th to 100th.

We further investigate the link of productivity and wages with size and adopt an econometric strategy that focuses on these links within countries, 2-digit industries, and years. This strategy ensures that the relationship of wages and productivity with size at the macro level is not driven by sectoral specialisation of countries, aggregate time trends, or any unobservable characteristic that varies at the country-industry-year level.

We find that, in line with the existing literature, both productivity and wages increase monotonically with firms’ size in manufacturing. Conversely, the distribution is much flatter in non-financial market services, where firms of more than 20 employees pay on average rather similar wages to their workers, and exhibit very similar productivity levels (both LP and MFP). While on average small service firms pay higher wages and are more productive than their counterparts in the manufacturing sector, the opposite is true for large firms.

Given that the positive size-wage premium may, at least partly, reflect productivity differentials among firms of different sizes, we turn to investigating the direct link between wages and productivity. We ask ourselves whether wages respond more to firms’ productivity compared to size, and whether the relationship is similar across sectors. We do find that wages increase with productivity, and the relationship is very tight both in manufacturing and even more so in services.

The combination of these results suggests that size does not ‘mediate’ the relationship between productivity and wages in the service sector. When looking at data going beyond manufacturing, the ‘size-wage premium’ becomes instead a ‘productivity-wage premium’.

In an extended version of this study (Berlingieri et al. 2018b), we investigate whether existing explanations for the size premium can fully account for our findings. In particular, we control for firm age, capital intensity, skill and knowledge intensity, and industry concentration, allowing for a differential effect of these variables across size classes and industries.

As found in the literature, we confirm that these variables can explain some of the size premium found in manufacturing, but they do not fully account for it. In addition, and of particular importance for our focus, we find that they cannot fully explain the significant differential size premium between manufacturing and services.

Bringing inclusivity to productivity

These results have first-order policy implications for both workers and firms.

The traditional paradigm of a manufacturing economy, in which the most productive firms were also the largest and therefore shared the benefits of their high productivity with a very large number of workers, seems to have shifted in today's service economy.

Previous research has shown that there are large and growing productivity gaps between the most and the least productive firms, even within industries (Andrews et al. 2016, Berlingieri et al. 2017b). We add to this debate by showing that, contrary to the established ‘size-wage premium’, the most productive firms at the top are not necessarily the largest ones in terms of employment.

This fact increases the likelihood of productivity and wage gains being shared with fewer workers, which in turn increases the concerns regarding the inclusivity of the growth model of the new service economy. Policymakers might need to reflect on the potential implications that these trends have for perceived and measured inequality.

References

Andrews, D, C Criscuolo, and P Gal (2016), "The Best versus the Rest: The Global Productivity Slowdown, Divergence across Firms and the Role of Public Policy", OECD Productivity Working Papers No. 5, summarised on VoxEU here.

Berlingieri, G, P Blanchenay, and C Criscuolo (2017), “The Great Divergence(s)”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers No. 39, summarised on VoxEU here.

Berlingieri, G, P Blanchenay, S Calligaris, and C Criscuolo (2017), “The MultiProd Project: A Comprehensive Overview”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Paper No. 2017/04.

Berlingieri, G, S Calligaris, and C Criscuolo (2018a), “The Productivity-Wage Premium: Does Size Still Matter in a Service Economy?”, AEA Papers and Proceedings 108: 328-33.

Berlingieri, G, S Calligaris, and C Criscuolo (2018b), “The Productivity-wage Premium: Does Size Still Matter in a Service Economy?”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers No. 2018/13.

Bloom, N, F Guvenen, BS Smith, J Song, and T von Wachter, (2018), “The Disappearing Large-Firm Wage Premium”, AEA Papers and Proceedings 108: 317-22.

Moore, HL (1911), Laws of Wages: An Essay in Statistical Economics, New York: Macmillan Company.