One consequence of monetary easing in major economies most affected by the financial crisis is the subsequent currency appreciation in apparently separate economies that are less affected by the crisis, such as those of Japan, Switzerland, and many emerging economies. Policymakers in these countries have, to varying extents, resisted the appreciation of their currencies by intervening in the foreign exchange market. Increasingly, observers have emphasised the potential for currency tensions under the current circumstances. Daniel Gros argues in “[a]n overlooked currency war in Europe” (Gros 2012) that intra-European interventions have had a “beggar-thy-neighbour” effect.

Beggar thy neighbour, love thy neighbour

Interventions tend to loosen monetary conditions globally, owing to mutually reinforcing public purchases in global bond markets. In particular, reserve managers at central banks that buy major currencies in order to resist currency appreciation stand shoulder-to-shoulder with other major central banks in their bond markets. When intervening authorities invest foreign exchange proceeds in major government bond markets, common practice among reserve managers, they join major central banks on the bid side in bond markets.

If government bond-buying by the major central bank eases monetary conditions, then reserve managers’ bond-buying must also ease monetary conditions. Thus, even if different authorities work at cross-purposes in the currency market - what, in this context, Joan Robinson (1937) originally called beggar thy neighbour - it is still important to recognise that there are also reinforcing actions in the bond market - what Clair Jones (2012) calls love thy neighbour.

The case of Japan

Reserve management has other effects. The most notable is a global portfolio rebalancing that pushes down bond yields in other countries. We have modelled this effect using daily data from the 2003-2004 episode of Japanese interventions against the US dollar (Gerlach-Kristen et al. 2012).

The Japanese property bubble burst in 1991, and the economy has since been characterised by low growth and phases of moderate deflation. In response, the Bank of Japan cut interest rates to close to zero in 1999 and adopted quantitative easing in 2001. In January 2003, the Japanese Ministry of Finance began to intervene in the foreign exchange market to counter an appreciation of the yen against the US dollar that had begun a year before.

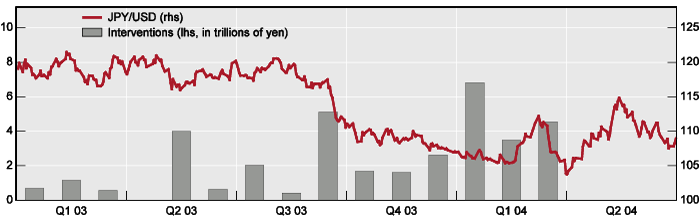

Figure 1 shows the intervention data together with the JPY/USD exchange rate. The Japanese Ministry of Finance managed to hold the yen stable - mostly in the 117-120 range - against the US dollar until August 2003. Around that time, international political pressure and capital inflows posed significant challenges to an intervention policy. On 16 March 2004, at an exchange rate of 106, the Ministry of Finance ceased intervening. It had acquired 35 trillion yen ($340 billion) over its 15 months of intervention, amounting to roughly 7% of Japanese GDP.

Figure 1 Ministry of Finance’s foreign exchange interventions

Sources: Japanese Ministry of Finance; national data.

When the Ministry of Finance buys US dollars against yen, it is generally thought to invest the dollar proceeds in US government bonds. Bernanke et al. (2004) show that, ceteris paribus, sizeable purchases of Treasury bonds drove down US yields in 2003-04. If investors rebalanced their portfolios internationally, or if market-makers anticipated their doing so, we would also expect bond yields in other currencies - including the Japanese yen - to decline. However, this effect should really only be found for economies whose bonds serve as close substitutes for US bonds.

Following Bernanke et al. (2004), we regress the daily change in the ten-year US government bond yield on the intervention amount instigated by the Ministry of Finance. To account for the time that passes between the striking of the foreign exchange deal and its actual settlement and possible investment, we consider the change in yield from the day before the deal until two days after1. Our approach allows for changes in global risk aversion, as measured by the Chicago Board Options Exchange market volatility indicator (VIX), to affect bond yields.

The effect on the global portfolio balance?

We test for a global portfolio balance effect by considering potential close substitutes from other advanced economies’ bond markets. We thus use ten-year government bonds from France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, Spain, the UK, Switzerland, and Japan. We also examine the effect on emerging market government bonds. Since these vary in their integration with global bond markets and thus in the degree to which they serve as substitutes for US Treasuries, we expect to find varied effects. For these emerging market bonds, we use 10-year yields for China, India, Malaysia, Mexico, Singapore, Chinese Taipei, and Thailand.

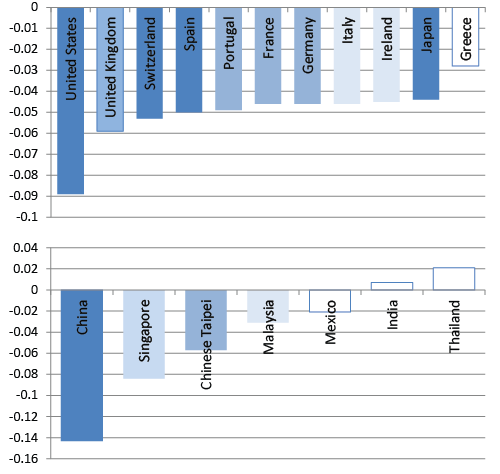

Figure 2 shows the estimated impact of Japanese interventions on government bond yields.2 We denote significance levels by shading intensity: dark bars are significant at the 1% level, while lighter shades indicate significance at the 5% and 10% level. The unfilled, white bars indicate insignificance.

The effect on advanced economies

Concentrating first on the effect on advanced economies’ bond yields in the top panel, we find the strongest response is in the US. We estimate that one trillion yen of intervention lowered the US bond yield by 8.9 basis points. But we also find reactions in the yields of bonds that serve as close substitutes for US bonds. The second strongest impact is detected for UK government bonds, the yields on which decrease by an estimated 7.2 basis points. Government bond yields across the rest of Europe respond similarly, with drops between 4.5 and 5.0 basis points. The notable exception is Greece, where we do not find a significant reaction. It seems that as early as 2003-04 bond investors viewed Greek government bonds as different and, presumably, as embodying more idiosyncratic risk. Furthermore, Ministry of Finance interventions seem to have lowered yields even in Japan, where the ten-year government bond yield is estimated to have dropped by about 4.4 basis points.

Figure 2 Response in basis points of ten-year government bond yields to JPY 1 trillion intervention

The effect on emerging market economies

The lower panel in Figure 2 reports results for emerging market economies. We find strong and significant responses to Japanese interventions in much of Asia, though the reaction of Chinese bond yields at 14.3 basis points seems anomalously large. Generally, significance levels are lower than for advanced economies, which may well be due to less integration with global bond markets and therefore lower substitutability with US government bonds.3

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that the investment of the proceeds from the Japanese foreign exchange interventions in 2003-04 in US Treasury bonds exerted a global effect. In particular, it appears to have lowered government bond yields in a range of industrial countries, including Japan, and those of emerging market economies whose bond markets are globally integrated. This points to a global portfolio balance effect that reflects the global integration of many bond markets.

Currency wars

These findings afford a new perspective on what has been called the currency wars. If the proceeds of large-scale currency interventions are invested in major bond markets, these incidental large-scale bond purchases can ease monetary conditions abroad in economies with internationally integrated bond markets.

Whether this effect is welcome depends on the phase of the business cycle in individual countries. Given the state of the US economy in 2003, the US authorities might well have welcomed lower bond yields that were a side effect of Japanese intervention, even if they did not welcome the intervention itself.

Implications for the Eurozone

It has been argued that investment of the proceeds of recent Swiss intervention has lowered yields on the government bonds of higher-rated sovereigns in the Eurozone, which can be expected to stimulate interest-sensitive spending there even whilst it widens intra-Eurozone spreads.4 If heavy intervention by emerging market economies in the mid-2000s led to lower US Treasury yields when US monetary policy was tightening,5 back then, the monetary easing as a by-product of intervention was certainly less welcome. Much depends on the respective phases of the business cycles. In any case, the effects herein detailed deserve to be systematically taken into account by current Eurozone policymakers (Caruana 2012).

Authors’ note: The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the BIS.

References

Bernanke, B, V Reinhart, and B Sack (2004), "Monetary policy alternatives at the zero bound: An empirical assessment", Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 35(2): 1-100.

Caruana, J (2012), "Policymaking in an interconnected world", speech to the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Symposium, Jackson Hole, 31 August.

Gerlach-Kristen, P, R McCauley and K Ueda (2012), "Currency intervention and the global portfolio balance effect: Japanese lessons", BIS Working Paper, 389.

Gill, F and I Morozov (2012), "How the Swiss National Bank is driving down yields for the Eurozone core", Standard and Poor’s Ratings Direct, 24 September.

Greenspan, A (2005), "Testimony on the Federal Reserve Board's Semiannual Monetary Policy Report", before the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, US Senate, Congress, 16 February.

Gros, D (2012), "An overlooked currency war in Europe", VoxEU.org, 11 October.

Jones, C (2012), "Currency wars: more love-thy-neighbour than beggar-thy-neighbour?", FT.com Money Supply, 3 October.

Robinson, J (1937), Essays in the theory of employment, Oxford, Basil Blackwell.

Warnock, F E and V C Warnock (2009), “International capital flows and US interest rates”, Journal of International Money and Finance 28, 903-919.

1 More precisely, we fit it+2 - it-1 = c + a*interventiont+ b* (vixt+2 - vixt-1) + et where we measure the foreign exchange interventions in trillion yen.

2 More precisely, it is coefficient "a" in the regression equation (1).

3 Ten-year government bonds are not very liquid in some emerging markets. Concentrating on the main maturities, we find that yields on five-year government bonds in Hong Kong and on three-year government bonds in the Philippines seem to have fallen in response to MoF purchases of dollars. We find no significant impact on one- to two-year Brazilian government notes, three-year Korean and seven-year Indonesian government bonds.

4 See Gill and Morozov (2012). The Swiss National Bank argued in response that the ratings analysts overstated the Swiss investment in European government bonds.

5 This factor was considered by Chairman Greenspan (2005) in his testimony that referred to bond yields as a “conundrum”: “long-term interest rates have trended lower in recent months even as the Federal Reserve has raised the level of the target federal funds rate by 150 basis points. This development contrasts with most experience, which suggests that, other things being equal, increasing short-term interest rates are normally accompanied by a rise in longer-term yields”.See Warnock and Warnock (2009).