Throughout history, commodity exporters have been blessed and cursed by the boom-and-bust nature of commodity-price and demand swings (see Spatafora and Tytell 2009).

For example, since 2002 or so, commodity exporting countries in Latin America have benefited largely from the commodity-price boom. Amid the associated terms-of-trade boom, key economic fundamentals in many of these economies strengthened markedly (Figure 1). This fed a sense that the macroeconomic response to the terms-of-trade shock was different, and more prudent, than to past ones. Whether this is the case, however, remains an open question.

Figure 1. Emerging Latin America: Terms of trade and seleceted fundamentals, 2002-20121

Sources: IMF, International Financial Statistics; and IMF country desks.

Notes: 1Emerging Latin Americca includes Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

2Of good and services.

We address this issue in a recent paper that studies the recent boom in historical and international perspective by documenting episodes of large terms-of-trade shocks from 1970 to the present for a sample of 180 countries (Adler and Magud 2013). Focusing on episodes that entail terms-of-trade increases of at least 15% cumulative (and 3% per year on average), we identify 270 events over this period encompassing low-income countries, emerging markets, and advanced economies.13% of the events took place in emerging Latin America alone.

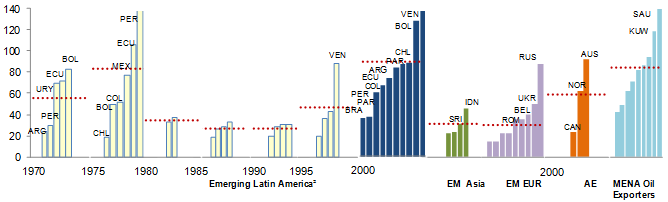

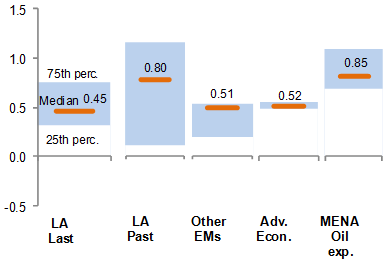

The region’s recent terms-of-trade shock has been sizeable – with a median increase of about 80%. Only the oil exporters in the Middle East and north Africa experienced a shock of similar magnitude (Figure 2). A historical view, however, shows that, while large, Latin America’s recent boom has not been significantly larger than those of the 1970s. Yet, there is a stark difference in terms of how much fundamentals have improved, now and then. This may have led to the idea that the macroeconomic response has been more prudent this time. But we argue that this is not the case. Rather than a greater ‘effort’ to save the terms-of-trade windfall, the improved fundamentals reflect a much larger shock than in the 1970s when one focuses on the ‘income windfall’ associated to the terms-of-trade boom, which is a more meaningful measure of the economic size of the shock.

Figure 2. Emerging Latin America and selected regions: Terms-of-trade booms, 1970-2012 (percentage change, cumulative during upswing)

Sources: IMF, International Financial Statistics; and authors' estimates.

Notes: 1Cumulative percentage change in terms of trade (of goods and services) from start to peak of each identified episode (that meets the criteria of at least 15% cumulative and 3% average increase). Episodes are grouped in five-year windows according to the date of their first year. Dotted lines indicate group averages.

2Emerging Latin America includes Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

An income windfall metric

Our measure of ‘income windfall’ computes the additional income that arises from changes in the real ‘purchasing’ value of output (in terms of the average consumer’s consumption basket) as a result of the changes in relative prices only.1 We focus on the impact on income rather than output, as these two tend to diverge markedly (as the GDP deflator and the CPI do) when there are large terms-of-trade shocks. This is a key innovation relative to other recent studies on the impact of external factors on emerging economies, which have focused on the effects on output rather than income.2

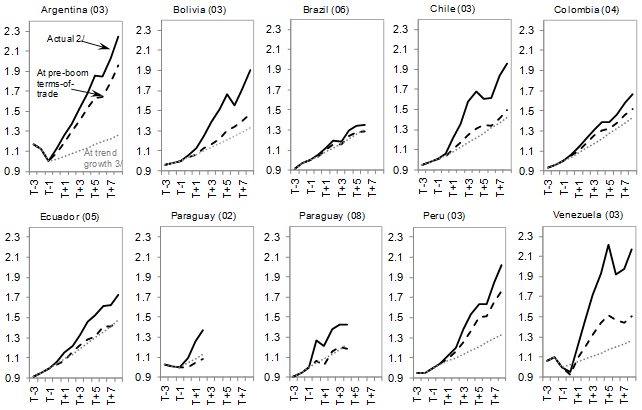

Figure 3 illustrates the relevance of the income windfall for some countries that witnessed terms-of-trade booms, Chile and Brazil being interesting opposite cases. In Chile, improvements in real income have come primarily from the terms-of-trade income effect (i.e. a substantial income windfall), unlike in Brazil where (owing to the lower degrees of trade openness and commodity reliance) this effect has been much smaller.

Figure 3. Emerging Latin America – recent episodes: Real domestic income1

Source: Authors' estimates.

Notes: 1First year of the episode is reported in parenthesis.

2Real gross domestic income, as defined in Adler and Magud (2013).

3Projected at long-term GDP growth rate (average of 1970-2012).

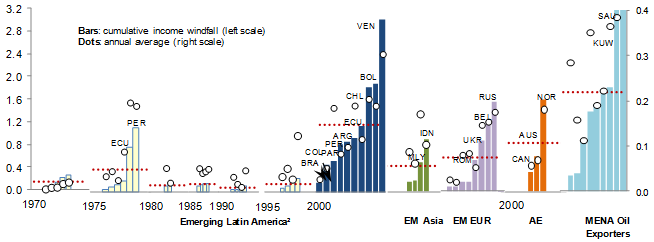

A historical comparison of terms-of-trade booms based on our measure of income windfall points to a much stronger impact in the recent episode than in past ones (Figure 4), reflecting a higher openness to trade amid a longer duration this time. Our estimates are sizeable also in absolute terms: during the recent episode real income has been on average close to 15% higher than what it would have been had no terms-of trade shock occurred. Furthermore, given its duration, the average cumulative windfall over the entire episode has been of about 100% of a year’s GDP.

Within Latin America, Bolivia, Chile, and Venezuela appear to have benefited the most. Cumulative (annual average) windfalls reached 300 (30)% of income in Venezuela and close to 200 (20)% in both Bolivia and Chile. Not surprisingly, Brazil stands at the other extreme of the distribution, with significantly lower windfall estimates.3 Again, only the oil-exporting countries in the Middle East and north Africa witnessed income windfalls of this order of magnitude.

Figure 4. Emerging Latin America and selected regions: Income windfall, 1970-20121

Sources: IMF, International Financial Statistics; and authors' estimates.

Notes: 1Cumulative and annual average income windfall, as share of GDP, from start to peak of each identified episode (that meets the criteria of at least 15% cumulative and 3% average increase). Episodes are grouped in five-year windows according to the date of their first year. Bars indicate cumulative values, dots indicate annual averages, and dotted lines indicate group averages for cumulative values.

2Emerging Latin America includes Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

Saving/investment patterns

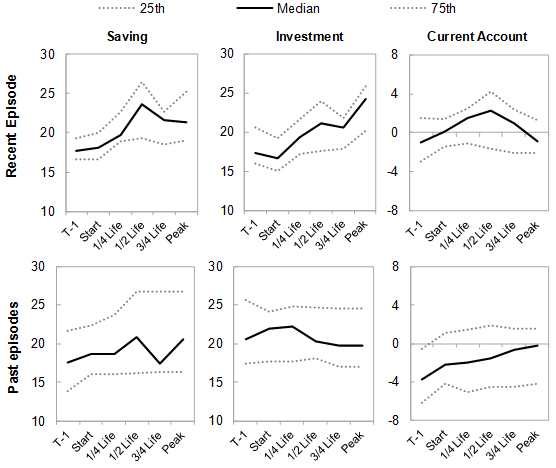

What has the macroeconomic response to this unprecedented shock been? Aggregate saving rates suggest that, compared with the past, Latin America’s response to the recent terms-of-trade episode has been more prudent (Figure 5). The median saving rate has increased about five percentage points of GDP, as opposed to two to three percentage points in past episodes. This has been accompanied by a remarkable expansion in the investment rate, unlike in the past. In turn, current accounts improved during the first stages of the recent episode, yet have deteriorated more recently as investment outpaced saving, also contrasting with past episodes.

Figure 5. Emerging Latin America: Savings, investment, and current account during terms-of-trade booms1

Source: IMF, International Financial Statistics; and authors' calculations.

Note: 1Episode length is normalised in order to allow aggregation, and series are reported at fractions of the lifetime of each event.

These standard measures of saving and investment rates, however, are affected by the size of the income windfall and do not provide an accurate gauge of how much of the windfall has been saved (i.e., the ‘marginal’ rates). Thus, we compute the marginal rates. These measure the extra (boom-time) saving over its ‘norm’, as a proportion of the income windfall. In addition, to look at how this saving is allocated, we compute the marginal rates for domestic and foreign saving (i.e., how much of the marginal saving was devoted to domestic capital formation and how much to foreign asset accumulation, respectively).

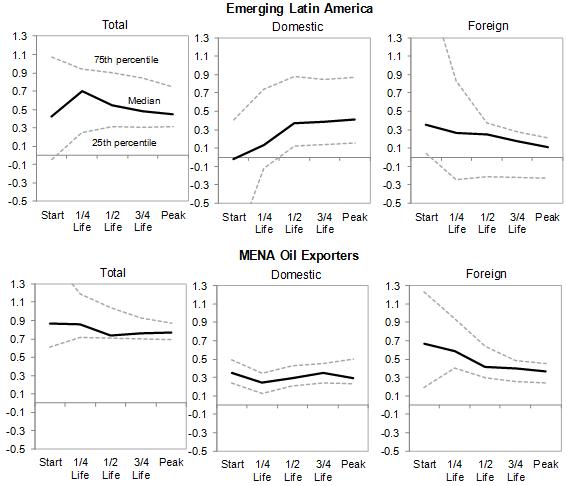

Interestingly, we find that Latin America’s marginal saving rates have been lower in the recent episode than in past ones (with medians of 45% vs 80%). This suggests that the ‘effort’ to save the windfall has actually been weaker (Figure 6). Furthermore, the dynamics of marginal saving rates in the recent episode depict a gradual decline over time. And the decomposition of saving rates shows a growing share of the windfall being allocated to domestic capital formation rather than to improving the country’s net foreign-asset position (via a strengthening of the current account).

Figure 6. Latin America and other groups – Current episode: Windfall saving1 (cumulative, as a share of income windfall; medians and 25th and 75th percentiles)

Sources: IMF, International Financial Statistics; and authors' estimates.

Note: 1Marginal savings rates as defined in Adler and Magud (2013).

Two issues regarding these responses deserve particular attention:

- First, Latin America’s recent lower marginal saving and higher investment rates could suggest that the terms-of-trade shock is increasingly perceived as more persistent, or that these economies are responding to the sharp drop in global interest rates that followed the global financial crisis.

However, the dynamics in Middle East and north African oil-exporting countries (Figure 7) – with income windfalls of similar magnitude to those in Latin America – do not support these hypotheses. In fact, Middle East and north African oil exporters have saved a much larger share of their income windfall (similar to their own past episodes) and have not witnessed meaningful increases in investment, despite having been subject to the same common global shocks. The result has been sizeable and sustained current-account surpluses in these countries, as opposed to Latin America.

Figure 7. Emerging Latin America and MENA oil exporters: Windfall saving rates1 (cumulative, share of income windfall; medians, and 25th and 75th percentiles)

Source: IMF, International Financial Statistics; and authors' estimates.

Note: 1Episode length is normalised in order to allow aggregation, and series are reported at fractions of the lifetime of each event.

- Second, increasing investment and weakening current accounts in Latin America may be consistent with a need to accumulate physical capital.

Yet, it is an empirical question whether domestic investment or foreign-asset accumulation is preferable as a saving ‘instrument’, in terms of its ability to deliver higher post-boom income.

Windfall saving and post-boom income

To assess the effects of saving during terms-of-trade booms on the level of post-boom income we regress the level of real income five years after the boom ends on our measure – and its subcomponents – of boom-time windfall saving.

We find that, as expected, higher windfall saving does increase post-boom real income. More interestingly, the composition of the windfall saving matters, as the payoff from allocating saving to foreign assets rather than to domestic investment is higher. This happens despite the fact that the sample of episodes is mostly composed of developing economies (where a higher return on capital would be expected). The result may reflect that the abundance arising from large terms-of-trade booms often leads to resource misallocation, or that weak underlying current-account positions end up being a drag on growth once terms-of-trade booms revert. Interestingly, these effects appear to be particularly strong for Latin America, likely reflecting its history of poor performance following terms-of-trade booms in previous decades.

Conclusions

Although Latin America’s recent terms-of-trade boom is of similar magnitude to that seen in the 1970s, the associated income windfall has been much larger. And only oil-exporting countries in the Middle East and north African region experienced similar shocks.

- The sizeable improvements in aggregate saving rates in the recent episode, as opposed to past episodes, suggest a more prudent response this time around.

- Yet, estimates of marginal saving rates suggest a weaker effort this time – unlike oil exporters in Middle East and north African countries – thus implying that the observed improvement in fundamentals is mostly driven by the sheer size of the income windfall.

- Finally, although saving the windfall pays off by increasing post-boom income, its allocation matters: in past episodes, foreign savings delivered higher post-boom income than domestic savings.

Hence, the current weakening of external current-account balances in Latin America –even if driven by higher domestic investment – warrants a close monitoring.

Disclaimer: The views expressed herein are those of the author and should not be attributed to the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management.

References

Adler, G and N Magud (2013), “Four Decades of Terms-Trade Booms: Saving-Investment Patterns and a New Metric of Income Windfall”, IMF Working Paper 10/103, Washington, International Monetary Fund.

Céspedes, L F, and A Velasco (2011), “Was This Time Different? Fiscal Policy in Commodity Republics”, BIS Working Papers 365, Basel, Bank for International Settlements.

1 Thus, it provides a lower bound estimate of the effect of the shock. The increase in output in response to the change in relative prices, not included here but shown in the paper, would add to this measure.

2 See, for example, IADB (2008), Izquierdo et al (2008), Osterholm and Zettelmeyer (2008), and Cespedes and Velasco (2011).

3 Although countries such as Mexico and Uruguay may have benefited indirectly from the recent terms-of-trade boom of some of their neighbors, they have not faced sufficiently large terms-of-trade shocks (as traditionally defined) to be considered boom-cases.