The world has globalised massively, but Bardhan (2003) and many others worry that academic publication has not. He asserts that researchers working on countries other than the US do not get a fair deal in the top economic journals. While work by Ellison (2000) documents how publishing in economics has changed over time, it is interesting to ask, at the end of three decades of globalisation, how global journals are today and whether publications in economics have become more representative of the world over time.

New evidence

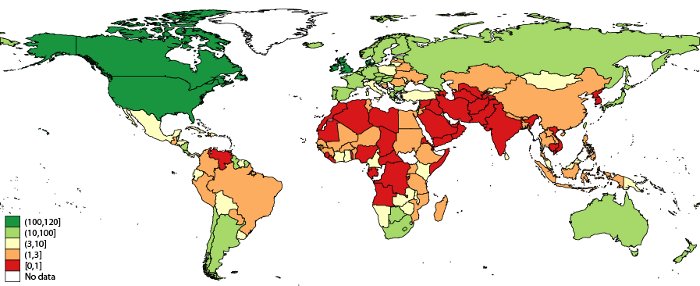

To address these questions, we draw on a database of 76,046 empirical papers published between 1985 and 2004 in the top 202 economics journals (Das et al. 2013). We provide basic facts on the country focus of empirical economics research and the likelihood of publication in top journals for research on the US and on other countries. The newly-assembled dataset first highlights just how little empirical research there is on low-income countries. Over the 20-year span considered, there were four papers published on Burundi, 9 on Cambodia, and 27 on Mali. This compares to the 36,649 empirical economics papers published on the US over the same time-period (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Total publications per million citizens

The strongest determinant of per-capita research output on a given country is its per-capita GDP, which alone accounts for 75% of the variation in (per capita) publications across countries. This relationship also accounts for the wide disparity in the extent of empirical research on the US and other countries. Although nearly half of all empirical economics publications over the 20-year period are on the US, it is not an 'anomaly'. Rather, the US is 'different' only in that it is both large and rich.

We then extend the analysis in two ways.

- First, we assess the role of data in the production of research by explicitly accounting for country-level measures of data availability and quality;

- Second, by looking at the patterns of research output following the release of major household surveys.

On both fronts, we are unable to find a smoking gun.

Although it is certainly possible to find small effects, in general there is little evidence of a substantive increase in publications after new data are released, even when it’s the first systematic survey available in that country. At first glance, lack of data does not seem to be the main impediment in the production of research. Second, we examine whether the relationship between research and GDP has changed over time. It has not. In 1985, every (log point) increase in GDP per-capita led to an additional 17-18 papers per year and by 2005, the relationship strengthened somewhat to 20-23 papers per year, although the difference is not statistically significant. The results are similar for research initiated in the top five universities; if anything, the income elasticity of research appears to have marginally increased over time in these institutions.

Although not an explicit focus of our paper, we also note that the research-wealth relationship in academic institutions is very different than in the research departments of multilateral institutions like The World Bank and the IMF. In these groups, the research-wealth elasticity is lower to begin with (even excluding the US from all calculations) and has been falling over time. By 2005, the elasticity was zero with equal work produced on poor and rich countries within the research groups of these institutions.

American exceptionalism in top journals

The surprising lack of American exceptionalism in the production of all research no longer holds when we look at the journals in which this research is represented.

- The probability of publication in a top-five economics journal is much larger for papers on the US relative to other countries.

The raw numbers are informative.

- The American Economic Review has published one paper on India (on average) every two years and one paper on Thailand every 20 years.

Neither are these numbers particular to this prestigious journal.

Considering the 20-year span (1985 to 2004) and the top-five economics journals together the published articles comprised:

- 39 papers on India,

- 65 papers on China, and

- 34 papers on all of Sub-Saharan Africa; and

- 2,383 papers on the US.

Here the top-5 is The American Economic Review, Econometrica, The Journal of Political Economy, The Quarterly Journal of Economics and The Review of Economic Studies.

Is it quality?

Does this seemingly over-representation of US-oriented papers due to higher quality? At first glance, the data suggest such a possibility. For instance, among the Top-5 ranked economics departments in the world (Harvard, MIT, Stanford, Princeton and University of Chicago), 74% of all papers published have a US focus compared to 47% for all institutions taken together. However, further analysis shows that this cannot be the entire story.

In our regression analysis, we take into account the authors’ affiliations and research field to partially address whether differences in the quality of submission alone account for the predominance of the US in the top-5 journals. Even with these controls, papers on the US are 1.6 percentage points more likely to be published in the top five journals – a large effect as only 1.7% of all papers written about countries other than the US are published in these journals. While we recognise that other characteristics not accounted for in the analysis could be driving the US premium, at least the most obvious correlates of quality alone are insufficient to explain the differences observed in the data.

Conclusion

These results provide an empirical basis for a debate on the extent of economic research in different countries. In low-income-country contexts where optimal economic policy depends on local institutions, culture and geography, the relevance of US-based findings to policy is potentially limited. Country-specific research is therefore important. The strong relationship between publications and GDP that we document is troubling since it suggests that even if we agree that country-specific policies are a great idea, the knowledge base that can be drawn on for many poor countries is very thin. The findings in this paper also speak to the issue of career concerns in the economics profession. Given that the number of top-five journal publications significantly drives academic careers, a causal interpretation of the documented correlations would lend credence to Bardhan’s (2003) concerns about a possible misallocation of talent across research institutions and a diversion of research incentives away from the study of developing countries.

Authors' note: We thank Benjamin Daniels for assistance with the figure in this post.

References

Bardhan, P (2003), "Journal Publication in Economics: A View from the Periphery”, Economic Journal 113(488): 332-7.

Das, Jishnu and Quy Toan Do with Karen Shaines and Sowmya Srinivasan. 2013. “US and Them: The Geography of Academic Research.” Journal of Development Economics, 105: 112-130.

Ellison, G (2000), “The Slowdown of the Economics Publishing Process”, unpublished MIT.