In recent years, evidence has suggested that globalisation is a key driver in helping emerging economies to apply knowledge, regulations, and standards acquired from their Western counterparts in order to become more mature, reliable, and hence stable.1 Pazarbaşıoğlu et al. (2007) find that globalisation may have raised stability, reflected by decreasing bond spreads in emerging countries, lower cross-border capital flow volatility, and decreasing volatilities of bonds, equities, and foreign exchange rates in various countries. Moreover, in 2004, Ben Bernanke, now US Federal Reserve Chairman, titled the increasing stability of financial markets ‘The Great Moderation’ which was possibly caused by the many positive effects of globalisation.2

Stable economic development is one of the cornerstones of the strong and well-functioning economic system, domestically as well as globally. Globalised countries need sophisticated regulations that will serve well in times of global financial crisis and provide confidence in markets. Regulations need to be solid enough that the impact of a crisis can be managed effectively or cannot even arise. We derive thesis A: If a country is more globalised than others, its domestic stock market is less volatile.

During the transition to greater globalisation, risks may arise as application of new economic methodologies outpaces their understanding and control. One could expect that opening up to the world and amending business standards also involve higher volatility. The higher the speed of globalisation, the more risk involved if an economy’s growth rate outpaces the evolution of its standards. The high speed may also generate opportunities for speculation, uncertainty, and risk. We state thesis B: The transition towards globalisation creates financial instability.

Finally, we want to look for confirmation that regulations prove to be effective during times of global crisis as well. Hence, thesis C is that more globalised countries have less volatile stock markets even during financial crises.

Data on globalisation and risk

To determine the level of globalisation, I used the KOF Index of Globalisation, which measures several dimensions on a yearly basis for 122 countries over the period between 1970 and 2005. The overall Globalisation Index is a weighted average of three main dimensions – economic, social and political globalisation – that are composed of sub-indices.

Risk is measured by the volatility of a country’s representative stock market index. I calculated the yearly averages and standard deviations based on the daily closing prices and then derived values at risk on a 99.9% confidence level assuming a normal distribution of the closing prices. The risk for each country in each year was computed by dividing values at risk by the yearly average of closing prices. This has helped to eliminate the effects of different currencies, inflation levels, number of shares in the indices, and other index-specific characteristics. The final “Risk Indicator” measure is standardised and can thus provide a more accurate comparison of the levels of financial risk in each country studied.

The final set of data contains the KOF Index of Globalisation from 1994 to 2005, and the yearly Risk Indicator from 1998 to 2008 for 26 countries.3

Global trends

Diagram 1 shows the historical development of the average globalisation index and risk indicator across all countries. Average globalisation has increased throughout the last decade. The development of average risk across all countries is more volatile. Unsurprisingly, it peaks during the 1998 Asian crisis, the 2002-2003 slowdown, and the current financial crisis. Its 2004 low point was interpreted as evidence of moderation at the time.

Figure 1 Average globalisation and risk across all countries

The relationship between openness and risk

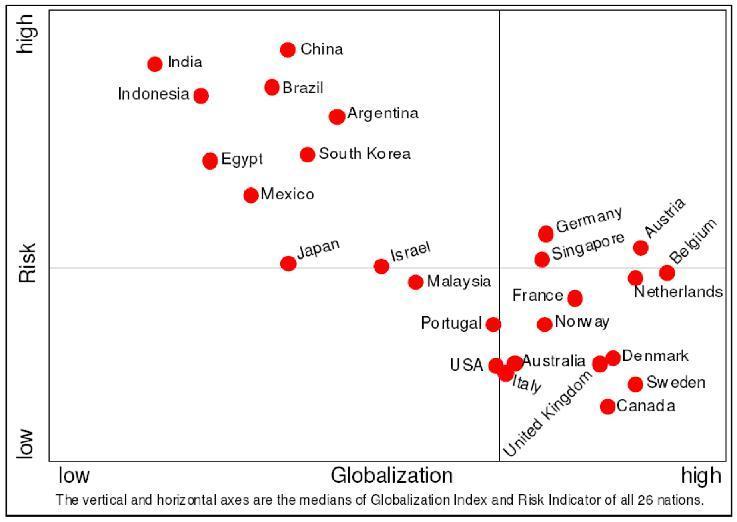

To explore the relationship between globalisation and risk for each country, I constructed an average of countries’ globalisation over the past ten years and corresponding risk over the observed time period.4 The results are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Globalisation and risk

Highly globalised countries are much less exposed to risk. Figure 2 implies that there is a strong and negative correlation between the level of globalisation and the level of risk.5 The finding supports the idea that countries with higher level of globalisation tend to have more mature economic systems with well-established regulations and sophisticated financial instruments. This generates more confidence in these markets, which is expressed in lower risk.

The group of countries with a low level of globalisation and high risk comprises countries from Asia and South America. Kose et al. (2007) argues that more developed countries have more stable financial markets because of greater developments and size, whereas less developed countries often suffer from “sudden changes in the direction of capital flows which tend to induce or exacerbate boom-bust cycles” and crisis.

Transition and risk

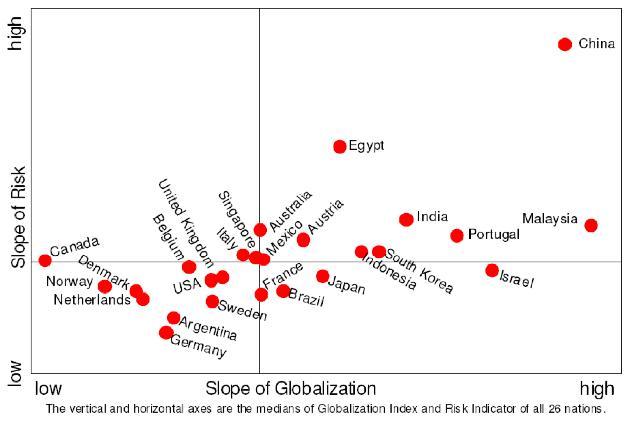

To look at the transition from a lower towards a higher level of globalisation, I examined the slopes of the globalisation index and risk indicator curves. The slope of globalisation index is strongly positively correlated with the average risk indicator, and even more strongly correlated with the slope of Risk Indicator. Increasing globalisation comes with greater risks, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Changes in globalisation and risk

China is the leader in terms of the progress made towards globalisation and the level of increased risk caused. China’s progress towards becoming a global economy is unique, but one may not oversee the possible costs of instability by facing high level and increasing risk already today even the stock market is small in terms of market capitalisation. As a result, in order to achieve higher efficiency in risk management and sustain stability and growth, more sophisticated and advanced regulations must be pushed forward and implemented in a timely manner.

Globalisation and risk during crises

We now want to explore the relationship of globalisation and risk during times of financial crisis. Table 1 shows the average correlation of 12 years of globalisation with the risk indicator. We can see that at the end of Asian Crisis in 1998, the strong and overall negative relationship between globalisation and risk does not hold. The same can already be observed for financial shock from terrorist attack in 2001 and the financial crisis in 2008. During these years, the superiority of globalised countries in terms of financial stability disappeared. Even worse, in the year of Enron accounting scandal, 2002, the mistrust in globalised countries economies became that large that the negative correlation changed into a positive, showing how vulnerable the confidence into the own systems is.

Table 1 Average correlation of 12 globalization indices for Year of Risk

| Year |

1998 |

1999 |

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

| Correlation |

-0.232 |

-0.719 |

-0.655 |

-0.105 |

0.465 |

-0.471 |

-0.555 |

-0.363 |

-0.603 |

-0.699 |

-0.368 |

N = 25, 1-tailed t-test probability < 0.1%/1% for abs(r) >= 0.588/0.462

Globalised countries tend to be less risky in times of financial stability. Unfortunately, in times of global financial instability these countries are not considered safe harbours to provide shelter from crisis. It seems that global instability makes market participants lose confidence in all markets regardless of where they are and where they have invested their money. Existing sophisticated regulations of globalised countries obviously do not provide the same confidence in times of turmoil as in stable times.

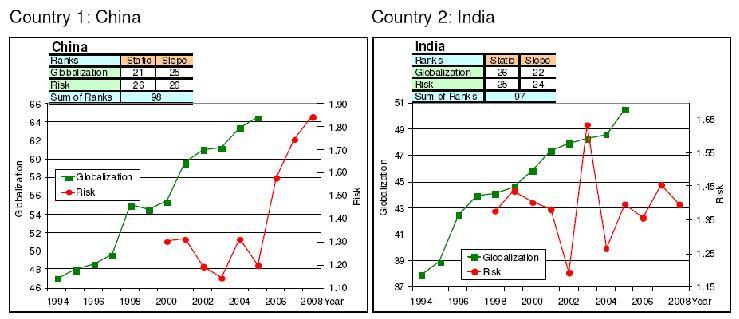

Developed and developing economies

In the final part of this analysis, I ranked all 26 countries observed in relation to the levels of their weighted average of Globalisation and Risk and the slope of these indicators respectively. The least globalised countries facing the greatest risk while in transition are China and India. Both countries are globalised on a relatively lower level but facing relatively higher level of risk. However, in the Chinese case, the risk indicator has dramatically increased in recent years, whereas India’s latest development has decreased its risk indicator.

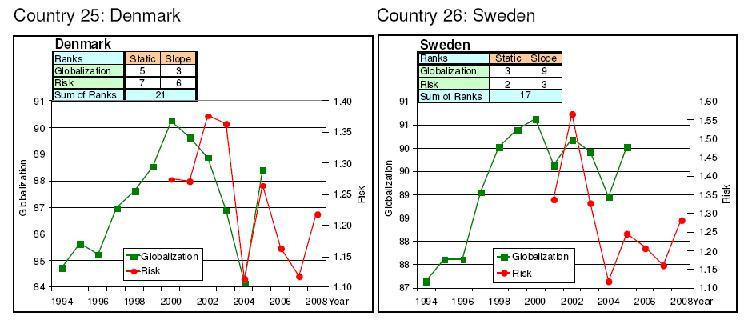

In the opposite circumstances are Denmark and Sweden. Both countries are operating on a very high level of globalisation with very stable financial systems, and are also showing a high degree of sustainability against the possible risks caused by globalisation.

A proposal for managing risk

Since the negative correlation between globalisation and risk vanishes in times of global financial crisis, one may ask if national economic systems are still not well prepared enough to cope with global financial instabilities. How come all seemingly well diversified and globalised economies need to be corrected so dramatically by a financial crisis? The answer is simple: In such a globalised world, kinetic energies of financial markets have become much bigger than before but are widely underestimated. Regulations for risk and liquidity reserves need to be reviewed and applied properly. But still, in such a globalised world, financial institutions may not be able to handle all risks by themselves anymore. The world financial community should go one step beyond the enhancement of existing instruments and establish a mutual approach towards the mitigation of global risk.

“Country risk banks” would be in charge of issuing risk certificates to be bought by a financial institution when issuing a financial loan product. The government would decide the volume of certificates available and the price determined by demand. The price paid for the certificate would be paid back after the loan or the investment has matured without default. In case of default, the government would keep the premium for the risk certificate to subsidise prices of risk certificates when necessary to stimulate the market and prevent future financial crisis. The number of certificates issued could be reasonably proportioned to economic indicators, e.g. proportionate to GDP, its growth, and the business forecast as well as according to general goals for a stable economy. Possibilities of fast-growing prices and hence risks of instability could be managed through adjustments of volume of risk certificates. The price of risk certificates would have an impact on the amount of risk a bank would be willing to take on.

A “global risk bank” should be in charge of coordinating the distribution of risk certificates in order to avoid earthshaking financial crises and provide more long-run financial stability. It should also initiate discussions among nations about the amount of risk they should be willing to take and facilitate political discussions about the right global approach for risk certificates.

References

Kose, M. Ayhan, Eswar Prasad, Kenneth Rogoff, and Shang-Jin Wei: (2007). “Financial Globalization: Beyond the Blame Game” Finance & Development, Volume 44, Number 11, March 2007.

Pazarbasıoglu, Ceyla, Mangal Goswami, and Jack Ree (2007) The Changing Face of Investors, Finance & Development, Volume 44, Number 11,March

1 The views expressed in this column are those of the author and do not represent the views of PriceWaterhouseCoopers.

2 Bernanke said: “The increased depth and sophistication of financial markets, deregulation in many industries, the shift away from manufacturing toward services, and increased openness to trade and international capital flows are other examples of structural changes that may have increased macroeconomic flexibility and stability.”

3 Country (Index): Argentina (Merval), Australia (All Ordinaries), Austria (ATX), Belgium (BEL-20), Brazil (Bovespa), Canada (S&P/TSX Composite Index), China (Shanghai Composite), Denmark (OMX Copenhagen 20), Egypt (CMA Gen.), France (CAC 40), Germany (DAX), India (BSE 30), Indonesia (Jakarta Composite), Israel (TA-100), Italy (MIBTEL), (Japan (Nikkei 225), Malaysia (KLSE Komposite), Mexico (IPC), Netherlands (AEX), Norway (Total Share), Portugal (PSI 20), Singapore (Strait Times), South Korea (Seoul Composite), Sweden (OMX Stockholm 30), United Kingdom (FTSE 100), and United States (S&P 500).

4 Globalization Index (GI) was available for 12 years for each country. The GI for 1994 was weighted by 1. The GI for 2005 was weighted 12 times. Risk Indicator (RI) was available for 11 years for each country. Hence, the RI from 1998 was weighted by 1 and the RI for 2008 was weighted 11 times. Globalization Index was found to be highly intra-correlated: Even with a time lag of 5 years, the average intra-correlation of GI is still +0.975. We concluded that the globalization index from 1994 to 2005 can reflect the current status of globalization until 2008 without serious distortion. Correlations between GI from a specific year with RI from all other years were also found to be very stable across all years, what supports this idea. Detailed results are

5 The correlation of weighted average GIs and RIs is -0.788, what is highly significant with a two-tailed probability of rejection of only 0.0003%.