Graduation from monetary policy procyclicality

How do emerging markets move from procyclical fiscal and monetary policies to countercyclical ones? This column argues that a key ingredient is stronger institutions.

Search the site

How do emerging markets move from procyclical fiscal and monetary policies to countercyclical ones? This column argues that a key ingredient is stronger institutions.

Start and stop, procyclical macroeconomic policies have been a chronic policy problem for emerging markets. Expansionary in good times and contractionary in bad times, booms become unmanageable credit expansions and ever-rising asset prices and busts turn into major recessions.

The problem of procyclical macroeconomic policies has, of course, also become an issue in industrial countries, as evidenced by the current austerity debate (Corsetti 2012). The perceived need for a fiscal contraction (or 'fiscal consolidation', to use the latest euphemism) in many Eurozone countries in the midst of a recessionary environment – presumably to reform the state, build credibility, and reduce debt levels – is very much reminiscent of similarly difficult choices faced by emerging markets in recent decades.

The traditional procyclicality of fiscal policy in emerging markets has been well documented by now. As discussed in Frankel et al. (2011), if one looks at the period 1960-1999, more than 90% of developing countries show procyclical government spending, compared to just 20% of industrial countries. Less well known, however, is the fact that over the last decade, many emerging markets have managed to escape the fiscal procyclical trap. Relying on data for 2000-2009, our work with Jeffrey Frankel (Frankel et al. 2011) finds that around 35% of developing countries ‘graduated’ (i.e., shifted from being procyclical to being countercyclical), and argues that such a dramatic shift can be explained by improvements in institutional quality, which are reflected in better fiscal institutions and fiscal policy rules based on cyclically-adjusted primary balances. Such rules help ensure that countries will save in good times and hence will be able to dissave in bad times.1

Monetary policy procyclicalityWhat about monetary policy? Do we observe the same historical pattern of procyclicality and recent graduation?2

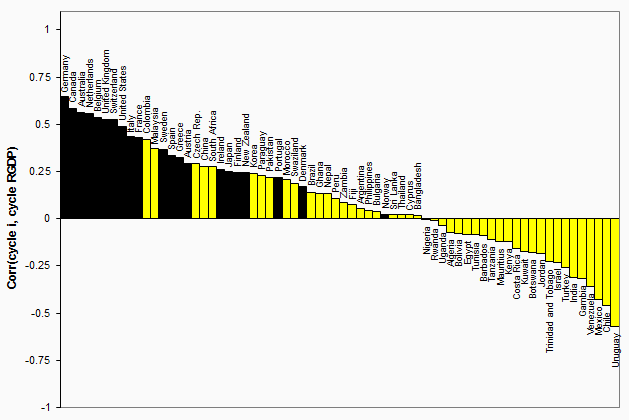

Figure 1. Country correlations between the cyclical components of policy interest rate and real GDP. 1960-1999

Figure 1 shows the correlation between (the cyclical components of) a policy (or short-term) interest rate and GDP for 1960-1999.3 Black (yellow) bars denote industrial (developing) countries. A positive correlation indicates countercyclical monetary policy (i.e., interest rates are raised in good times) while a negative correlation denotes procyclical monetary policy (i.e., interest rates are raised in bad times). The visual message is unmistakable: every single industrial country has been countercyclical, as reflected in all black bars lying on the left side of the picture. In contrast, 51% of developing countries have been procyclical. In fact, the average correlation for developing countries is -0.02% compared to 0.38% for industrial countries.

Figure 2. Country correlations between the cyclical components of policy interest rate and real GDP. 2000-2009

As in the case of fiscal policy, however, over the last decade many emerging markets have been able to escape the procyclical trap. To illustrate this, Figure 2 replicates Figure 1 for the period 2000-2009. Once again, the visual image conveyed by Figure 2 is striking when compared to Figure 1. The number of yellow bars on the left-side of the picture has greatly increased. Around 77% of developing countries now show countercyclical monetary policy, up from 49% in Figure 1.

Who graduated?Figure 3. Country correlations between the cyclical components of policy interest rate and real GDP. 1960-1999 vs. 2000-2009

To dig further into the issue of monetary policy graduation, Figure 3 presents a scatter plot with the 1960-1999 correlation on the horizontal axis and the 2000-2009 correlation on the vertical axis. By dividing the plot into four quadrants, we can classify countries into four categories:

1. Established graduates (top-right): Countries that have always been countercyclical. Not surprisingly, all industrial countries fall into this category. About 38% of developing countries also fall into this category (including Colombia and South Korea).

2. Still in school (bottom-left): Countries that were procyclical during 1960-1999 and have continued to be in the most recent period, including Costa Rica, Gambia, and Uruguay.

3. Back to school (bottom-right): Countries that were countercyclical during 1960-1999 and turned procyclical over the last decade, including Brazil, China, and Morocco.4

4. Recent graduates (top-left): Countries that used to be procyclical and became countercyclical over the last decade, including Chile and Mexico. All countries in this category are developing and account for 38% of all developing countries.

In sum, the evidence suggests that close to 40% of developing countries have recently graduated from monetary policy procyclicality. As a result, 77% of developing countries have followed countercyclical monetary policy over the last decade.

Fear of free fallingWhy have some developing countries been able to graduate and not others? While undoubtedly many factors come into play, we believe that a critical one is what we will refer to as the 'fear of free falling (FFF)'. In emerging markets, bad times typically coincide with heavy capital outflows and loss of policy credibility, which triggers substantial currency depreciation. This, in turn, further erodes credibility and exacerbates capital outflows. Faced with this dire situation, policymakers often have no choice but to increase interest rates to defend the domestic currency by making domestic-currency assets more attractive to hold. In fact, this was part of the standard economic package recommended by the IMF during the Asian crises.5 The fear or free falling thus prevents policymakers from lowering interest rates in bad times, as typically happens in industrial countries.6

Fear of free falling can therefore explain why emerging markets often have to reluctantly raise interest rates in the midst of a recessionary environment. Fortunately, this fear is not necessarily a chronic condition that emerging markets can never outgrow. Quite to the contrary, we have found that fear of freefalling is strongly correlated with available measures of institutional quality, such as indices of investment climate, corruption, law and order, and bureaucratic quality. As a result, in countries where institutional quality has improved over time, the fear of freefalling has gradually decreased over time.

Figure 4. Chile: Correlation between the cyclical components of policy interest rate and real GDP vs. fear of freefalling

To illustrate this point, Figure 4 plots for the case of Chile – a 'recent graduate' in our above classification – the 20-year rolling window for fear of free falling and the cyclicality of monetary policy. Our measure of fear of free falling (FFF) – which varies between zero and one – decreased from values close to 0.9 in the early 1980s to about zero in the late 2000s. In line with our arguments, monetary policy shifted from being markedly procyclical (with a correlation of around -0.8) to being countercyclical

ConclusionIn sum, our evidence strongly suggests that countries that have been able to develop stronger institutions over recent decades have been rewarded by being able to move from procyclical to countercyclical fiscal and monetary policy. While no panacea – as the recent experience of many industrial countries painfully suggests – many more emerging markets now have the ability to use all available policy tools to successfully sail through the unavoidable economic storms.

ReferencesCorsetti, Giancarlo (2012), “Has austerity gone too far?”, VoxEU.org, 2 April.

Frankel, Jeffrey (2011), “A solution to fiscal procyclicality: The structural budget institutions pioneered by Chile”, NBER Working Paper No. 16945.

Frankel, Jeffrey, Carlos A Vegh, and Guillermo Vuletin (2011), “Fiscal policy in developing countries: Escape from procyclicality”, VoxEU.org, .

Fischer, Stanley (1998), “The IMF and the Asian crisis”, Lecture delivered at UCLA (available on the IMF website).

Vegh, Carlos, and Guillermo Vuletin (2012), “Overcoming the fear of free falling: Monetary policy graduation in emerging markets,” in The role of Central Banks in financial stability: How has it changed?, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

1 Chile is clearly the poster child of this graduation movement; see Frankel (2011).

2 The remainder of this note draws heavily on Vegh and Vuletin (2012).

3 We use short-term interest rates as a proxy for the stance of monetary policy. In some cases, we have data for overnight interest rates, such as the Federal Funds rate in the United States. In most cases, however, we rely on discount rates due to their longer availability.

4 We should note that, taken together, the 'back to school' and 'still in school' categories represent less than 25% of all developing countries.

5 Stanley Fischer (1998), at the time the IMF’s First Deputy Managing Director and main policy architect, has argued that, “because the reserves in Thailand and Korea were perilously low and the Indonesian rupiah was excessively depreciated … the first order of business was to restore confidence in the currency" which required "increasing interest rates temporarily, even if higher interest rates complicates the situation of weak banks and corporations."

6 In Vegh and Vuletin (2012), we develop an empirical measure of FFF (the correlation between the cyclical components of the policy interest rate and the rate of depreciation) and show that monetary policy has been procyclical for high levels of FFF and become countercyclical as FFF diminishes.

3,674 Reads