By now just about everybody agrees that the European bailout of Greece has failed (see for example Darvas et al. 2011). The debt will have to be restructured. As has been evident for well over a year, it is not possible to think of a plausible combination of Greek budget balance, sovereign risk premium, and economic growth rates that imply anything other than an explosive path for the future ratio of debt to GDP.

There is plenty of blame to go around. But three big mistakes can be attributed to the European leadership. This includes the ECB – surprisingly, in that it has otherwise been the most competent and successful of Europe-wide institutions.

- Mistake number 1: The decision in 2000 to admit Greece in the Eurozone.

Greece was an outlier, geographically and economically. It did not come close to meeting the Maastricht Criteria, particularly the 3% ceiling on the budget deficit as a share of GDP. No doubt most Greeks would agree with the judgment that they would be much better off today if they were outside the euro, free to devalue and restore their lost competitiveness.

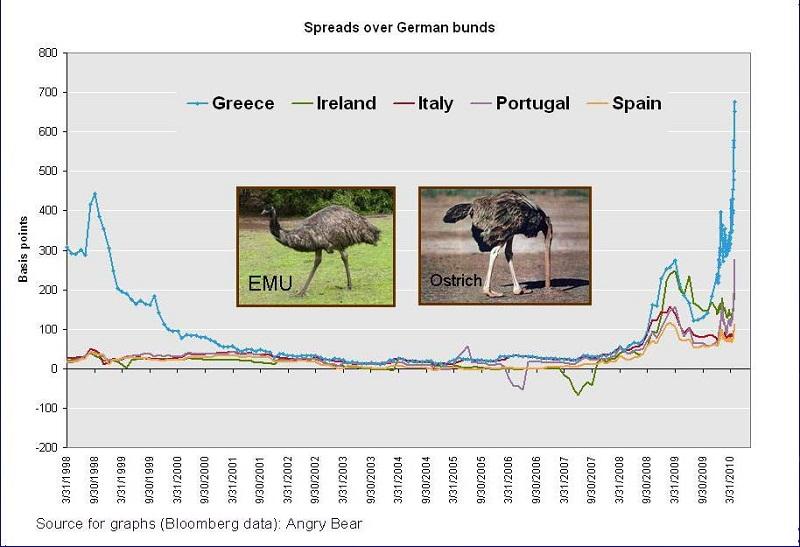

- Mistake number 2: Allowing the interest rate spreads on sovereign bonds issued by Greece (and other periphery countries) to fall almost to zero during the period 2002-2007.

Despite budget deficits and debt levels that far exceeded the limits of the Stability and Growth Pact, Greece was able to borrow almost as easily as Germany. Part of the blame belongs to international investors who grossly underestimated risk on all sorts of assets during this period (Frankel 2007). And part of the blame belongs to the rating agencies who, as usual, have been lagging indicators of European debt troubles, rather than leading indicators. But in this case, both groups might justify their attitudes by pointing out that the ECB accepted Greek debt as collateral, on a par with German debt.

- The third mistake was the failure to send Greece to the IMF early in the crisis.

By January 2010 the need should have been clear. Rather than going into shock, leaders in Frankfurt and Brussels could have welcomed the Greek crisis as a useful opportunity to establish a precedent for the long-term life of the euro (see Frankel 2010).

The idea that such a problem would eventually arise somewhere in the Eurozone cannot have come as a surprise. After all, why had the architects written the Maastricht fiscal criteria and the No Bailout Clause (1991) and the Stability and Growth Pact (1997)? Sceptical German taxpayers believed that, before the project was done, they would be asked to bail out some profligate Mediterranean country. European elites adopted the fiscal rules precisely to combat these fears.

When the rules failed and the crisis came, the leaders should have thanked their lucky stars that the first test case had arisen in a country that met two characteristics admirably.

- First, the Greek government had broken the rules so egregiously and so frequently that Europe’s leaders could, with a clear conscience, judge a firm stand to be merited.

The only alternative was to risk establishing the precedent that all governments are ultimately to be bailed out all the time, with all the moral hazard headaches that precedent implies.

- Second, the Greek economy was small enough to make it feasible for Europe to come up with the funds necessary to insulate others, who were vulnerable to contagion but not as blameworthy, for example Ireland.

European leaders also should have thanked their stars that the IMF exists. Instead of acting as if such a crisis had never been seen before, they should have realised that imposing policy conditionality in rescue loan packages is precisely the IMF’s job. International politics is less likely to prevent the IMF from enforcing painful fiscal retrenchment and other difficult conditions than it is among regional neighbours or other political allies. Europe is no different in this respect than Latin America or Asia. Even the need to include in the package substantial funds from regional powers on top of IMF money, subject to the same IMF conditionality, should have been recognised as familiar from big emerging-market crises such as those of the 1990s.

But the reaction of leaders in both Frankfurt and Brussels was that going to the IMF was unthinkable, that this was a problem to be settled within Europe. They chose to play for time instead, to treat insolvency as illiquidity (see Darvas et al. 2011). Against all evidence – and despite a decade of Stability and Growth Pact violations – they still wish to believe that they can impose fiscal discipline on member states. Despite two decades in which citizens of Germany and other European countries have expressed clearly that they do not share their leaders’ enthusiasm for Economic and Monetary Union (O’Rourke 2011), the latter apparently still wish to believe that further progress to political and fiscal union is possible. The Economic and Monetary Union has long since become an ostrich, burying its head in the sand.

It turned out that the German taxpayers were right all along. How, in light of that democratic deficit, can anyone think that Europe is ready for a transfer union?

Solutions looking forward

The three mistakes now lie in the past. How can Europe’s fiscal regime be reformed to avoid future repeats? The reforms in train are not credible. (“We are going to make the fiscal rules more explicit and make sure to monitor them more tightly next time” – see for example Thygesen 2011). But it is not too late to apply the lesson of mistake number two – the ECB policy of accepting the assets of all member states as collateral.

My proposal:

- The Eurozone should adopt a rule that whenever a country violates the fiscal criterion of the Pact (say, a budget deficit in excess of 3% of GDP, structurally adjusted), the ECB must stop accepting that government’s debt as collateral.

This system would achieve the elusive objective of true automaticity. If a country exceeded the threshold for justifiable reasons, such as natural disaster or war, the private markets could perceive that and impose little or no default-risk premium. No judgment of the merits by bureaucrats or politicians would be required. More likely, for periphery countries, the result of such a re-classification would be the re-emergence of sovereign spreads of moderate magnitudes, in between the extremes of the 2002-2007 lows and the 2009-2011 highs. The interest rate premium would send a message far more credibly, forcefully, and promptly than any warning that any Brussels bureaucracy will ever turn out.

This is how it works among the US states and municipalities (Bayoumi et al. 1995). Despite the absence of their own currencies, the recurrence of dysfunctional local politics and excessive deficits, and even a history of state defaults in the 19th century, federal bailouts are not delivered and not expected. Without some such device, the new European Stability Mechanism is in danger of becoming a mechanism for instability.

References

Bayoumi, Tamim, Morris Goldstein and Geoffrey Woglom (1995), "Do Credit Markets Discipline Sovereign Borrowers? Evidence from the US States", Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 27(4):1046-1059, November.

O’Rourke, Kevin (2011), “

A Tale of Two Trilemmas”, Challenge of Europe session, at the Institute for New Economic Thinking 2011 Annual Conference, Bretton Woods, 10 April.

Thygesen, Niels (2011), “Governance in the Euro Area”, INET 2011 Annual Conference, 10 April.