There is much disagreement among economists on whether variations in housing wealth matter for consumption. Attanasio et al. (2005) take the view that house-price fluctuations reflect shifts in income expectations and play no causal role for consumption. The Bank of England has long argued similarly that there is no housing wealth effect on consumption and Willem Buiter is among many supporting this view. The Bank persists in using a logically flawed argument as evidence: it points to the breakdown after 2001 in the simple correlation between house prices and consumption as evidence of lack of a causal connection. However, when multiple causes are at work – the stock-market crash and rising household indebtedness among them – simple correlations tend to shift.

Housing wealth effects via the credit channel

In Muellbauer (2008), I argue that a persistent medium-run ‘housing wealth effect’ on consumer expenditure works mainly via the credit channel. There have been major shifts in behaviour with credit market development. A liberal credit market tends to result in house prices having a positive effect on consumption as it relaxes owners’ collateral constraints and limits the young’s need to save for a housing deposit even at higher prices. With an illiberal credit market, the collateral effect is weak, while the need of the young to save for a housing deposit is greater with higher house prices. In the latter case, higher house prices reduce consumer spending, as seems to have been the case in Italy and Japan (Muellbauer and Murata, 2008). Institutional differences between countries therefore matter greatly, and so do proper controls for changing credit conditions and other drivers of consumption in econometric work, often omitted in the literature reviewed in Muellbauer (2008).

In Muellbauer (2008), I show that traditional life-cycle theory (without a credit story) implies that the effect of a permanent rise in the price of housing on aggregate consumption (including imputed rent) is negative. Relaxing some of the assumptions might give a small positive effect, at best. The Bank of England is broadly correct to assume there is no basis for a housing wealth effect in the traditional model. However, the limitation of the Bank of England’s model is that it is missing the credit channel –except via short-run dynamic effects in house prices.

Credit market evolution

The key features of credit market evolution have generally included the following:

- changes in prudential and wider capital-market regulations;

- technological change and reductions in the cost of information technology, giving rise to internet banking, and

- better sharing by lenders of information on borrowers’ credit histories.

The deepening of markets for securitised contracts and derivatives with financial globalisation has been another important feature. However, it has now been recognised that many of the developments, particularly since 2000, have been founded on misconceptions and a poor incentive structure for bankers and others selling financial products.

Britain’s experience

The United Kingdom also underwent a credit revolution. The elimination of exchange controls in 1979 integrated the United Kingdom into global capital markets. The key constraint on bank lending – the “corset” – was removed in 1980, so that banks crowded into domestic mortgage markets. The competitive response and relaxation of constraints on existing mutual mortgage lenders (formalised in the 1986 Building Society Act) further eased access to mortgage credit. A new breed of mortgage lender selling via intermediaries (the ‘centralised mortgage lenders’) entered the market from 1985. A partial retrenchment of credit conditions occurred in the early 1990s as it became clear that default risk insurance for major mortgage lenders had been under-priced. Later, more evolutionary changes described above shifted the credit supply function to a new plateau. These changes can be tracked in the form of an index.

Empirical determinants of housing credit conditions and wealth effects

In work with Emilio Fernandez-Corugedo, we construct a credit conditions index for the United Kingdom using loan-to-value (LTV) and loan-to-income (LTI) data extracted from the Survey of Mortgage Lenders (with over 1m observations, 1975–2001). The fractions of LTV and LTI ratios for first-time buyers above certain thresholds were extracted and classified by age and region to give eight series. Adding aggregate consumer credit and aggregate mortgage debt, gave a total of ten credit indicators. The credit conditions index was then estimated as a common factor in ten jointly estimated credit indicator equations – controlling for a rich set of economic and demographic factors.

To assess the housing collateral effect on consumption requires a modern version of the Friedman–Ando–Modigliani consumption function. The basic aggregate life-cycle/permanent-income consumption function says that consumption depends on current income, expected income growth and on asset wealth. Unlike the Euler equation popular in academic and central bank circles, it does not throw away long-run information on income and assets, nor does it rely on extreme assumptions about consumer rationality. It embodies simple folk wisdoms stemming from the long-run budget constraint. Consumers realise that future as well as current income matters and that if they spend too much of their wealth now, they have less to spend in future. This consumption function has advantages for policy modelling and forecasting. Incorporating an income-forecasting model to generate permanent non-property income and adding further realistic features such as habits, a role for variable interest rates and income uncertainty, splitting up assets into different types, and introducing a role for the credit channel gives rise to a very useful empirical model.

Housing wealth affect consumption only after credit market liberalisation

Estimates for the United Kingdom for 1967 to 2005 of such a modern version of the life-cycle model are presented in Muellbauer (2008). They confirm important shifts in behaviour with credit market development. Most importantly, for given assets and debt, credit market liberalisation substantially raised consumption relative to income, and housing wealth only began to matter for consumption after credit market liberalisation.

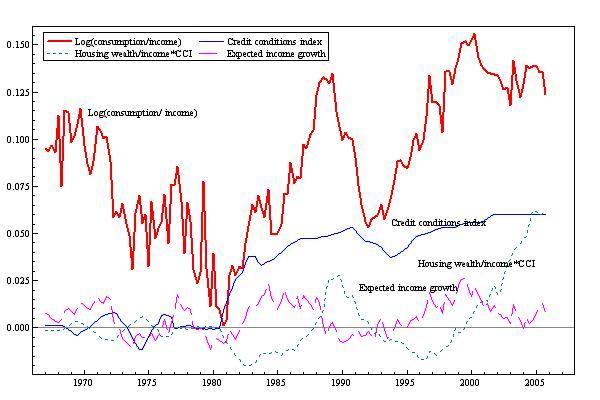

The long-run contributions of key drivers to the log consumption to income ratio are shown in Figures 1 and 2. Figure 1 shows the effect of the credit conditions index and the housing collateral effect on consumption, which rises with the index and appears to be close to zero before 1980. The figure also shows the contribution of the fitted forecast income growth rate over a three-year horizon. It can be seen that its contribution to the fall in the saving ratio (rise in log consumption relative to income) in the 1980s is small relative to the contributions of increased credit supply and the rise in housing collateral. The fall in the unemployment rate, not illustrated, also had an important effect from the mid-1980s.

Figure 1. Credit conditions, housing wealth, and consumption

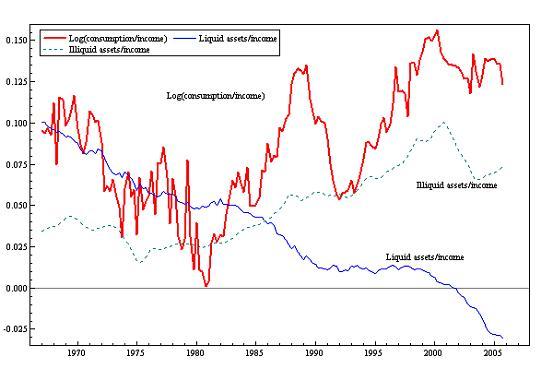

Figure 2 shows the contributions of illiquid financial wealth and of net liquid assets (liquid assets minus debt). The former reveals the clear impact of the fall in the stock market in the early 2000s. The latter shows the serious drag on spending coming from the increased indebtedness of UK households.

Figure 2. Wealth and consumption

Looking ahead

Looking forward, the research suggests a UK recession will be hard to avoid. Relative to mid-2007, the decline in the housing wealth to income ratio will soon reach 15%, which would eventually lower the consumption/income ratio by about 2.5 percentage points. But real household incomes are themselves falling, under pressure from oil and food prices. A further 1% or more fall in consumption is likely from the direct and interaction effects of the contraction of credit availability. On top of all that comes the effect of the fall in the stock market. The estimated adjustment speed in the model is 0.35 per quarter, so it takes several quarters for the full effects to show up.

The US situation

The US evidence is that the housing collateral effect is even larger than in the United Kingdom. Unlimited US tax relief on mortgage interest encourages home equity loans (tax relief in the United Kingdom was heavily restricted and is now zero). Interest-rate risk is far lower in the United States. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac underwrite “conforming” loans and, together with a deep financial sector, provide fixed-rate loans with cheap refinance options. In many US states, there is a “walk-away” mortgage default option, while in the United Kingdom, bad mortgage debts are pursued for up to 7 years. This is consistent with recent evidence of an asymmetry in the US collateral effect: falls in house prices matter less than in the UK because negative equity matters less.

The combination of credit channel and falling house prices have clearly negative effects on UK and US consumption. But institutional differences really matter. This source of economic downturn is more pronounced than it will be in Japan and Germany.

References

Attanasio, O., Blow, L., Hamilton, R., and Leicester, A. (2005), ‘Booms and Busts: Consumption, House Prices and Expectations’, Working Paper 05/24, Institute for Fiscal Studies, London.

Fernandez-Corugedo, E., and Muellbauer, J. (2006), ‘Consumer Credit Conditions in the UK’, Bank of England Working Paper 314.

Muellbauer, J. (2008), ‘Housing, Credit and Consumer Expenditure’, paper presented at Housing, Housing Finance, and Monetary Policy Symposium, sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, WY, 30 August–1 September.

Muellbauer, J., and Murata, K. (2008), ‘Consumption, Land Prices and the Monetary Transmission Mechanism in Japan’, paper presented at ESRI and the Center on Japanese Economy and Business (CJEB) at Columbia Business School, workshop on ‘Japan’s Bubble, Deflation and Long-term Stagnation’, Columbia University, 21 March.