A fierce policy debate with little insight from economists

Fears that immigration takes jobs away from natives and imposes significant costs on taxpayers continue to shape electoral campaigns and policy discourses in several countries. In a recent referendum, the Swiss population rejected the free movement of workers from the EU. In Germany, there are mounting fears that millions of poor immigrants from new EU member states would flock to the country, attracted by the generous welfare state. The UK Prime Minister David Cameron has argued in favour of significant restrictions on labour mobility within the EU to limit inflows to the UK. And in the US, in spite of the consensus that immigration laws need fixing, there are deep disagreements over how to go about it – especially when it comes to solving the problem of undocumented workers.

Economists have not been able to steer this debate much. While they have long been optimistic about the benefits of immigration (Borjas 1995) they have framed their analysis in simple, full-employment models that include neither redistribution nor unemployment. It is no surprise that policymakers have pointed at the high degree of abstraction of those models, arguing that they may miss very crucial features of reality. The canonical model, featuring full employment and wages equal to workers’ marginal productivity, finds a small surplus from immigration because immigrants contribute more to production than they earn as long as they have a different skill distribution from natives (Borjas 2003).

However, in many economies, wages are bargained over and are not set competitively. Moreover, involuntary unemployment exists, and labour markets are slow to adjust. Equally important and also missing in the canonical framework, welfare states redistribute from employed to unemployed and from rich to poor, which may imply a net transfer between natives and immigrants.

Making economic modelling relevant

Some recent papers (such as D’Amuri et al. 2010 and Felbermayr et al. 2010) have started to incorporate labour market frictions in the analysis of the effect of immigration. Those papers, however, have shied away from modelling in detail the process of job search and unemployment in labour markets. Also, some studies in the public finance literature – both theoretical and empirical – have studied the net contribution of immigrants to the welfare state (e.g. Dustmann and Frattini 2013, Boeri 2010). However, these papers have only accounted for some forms of redistribution, and certainly have not included a role for labour market imperfections.

In our recent working paper (Battisti et al. 2014), we have introduced wage bargaining, search frictions, and a redistributive welfare state into a framework that still includes skill complementarities between immigrants and natives in production. Hence the traditional, and important, channel of gains for natives (skill complementarity) is introduced in a much more realistic world of frictions and redistribution that can make immigrants costly for natives. We have then calibrated the model to match the average statistics that we observe for 20 OECD countries. We have also simulated two ‘counter-factual’ scenarios:

(i) How does native workers’ welfare compare between the status quo and a situation with no immigrants (closed borders), and

(ii) What has been the effect on native welfare of immigration during the last 10 years?

The relative labour-market performance of immigrants

Looking at the wages of natives and immigrants of similar skills across the 20 countries considered, some interesting regularities emerge. First, immigrants are usually paid less than natives with similar educational attainments. Second, unemployment rates are usually higher among immigrants.

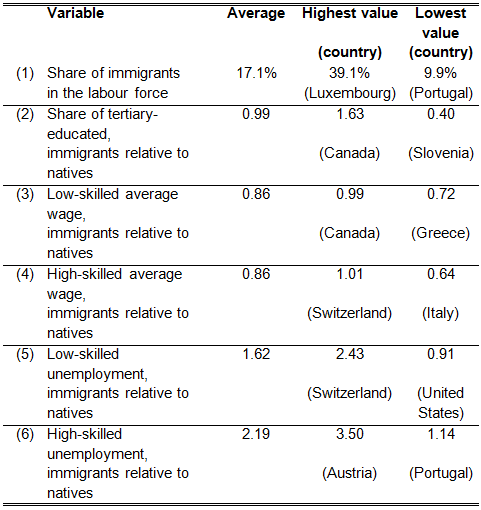

Table 1. Migrants versus natives: Cross-country heterogeneity within the OECD

Source: Battisti et al. (2014). Summary statistics based on a sample of 20 OECD countries.

Rows 3 and 4 of Table 1 show that, within education groups, immigrants receive lower wages than natives, and the gap is particularly important in the low-skilled segment. Moreover, as shown on rows 5 and 6, high- and low-skilled immigrants alike are also more likely to be unemployed. These differences – even allowing for reasonable differences in productivity – suggest that:

(i) Migrants have worse outside options than natives, and so obtain lower wages through bargaining, and

(ii) They are more likely to be hit by job destruction shocks, and so are more often unemployed.

How immigration can spur job creation

The introduction of job creation by firms – an important feature of our framework – generates two important effects of immigration. In particular, if firms cannot discriminate between natives and immigrants in the search process, but can pay immigrants lower wages (as is the case in the data), then the presence of immigrants drives up the average return from job creation. This encourages firms to create more jobs, some of which will be filled by natives. However, if matches with immigrants are more likely to break (as implied by their larger unemployment rate), the expected return to job creation is lower and firms will create fewer jobs. Which channel dominates depends on the relative strength of each mechanism. This can be simulated by our model once we have carefully calibrated its parameters on the data.

Figure 1. Native welfare changes in two migration scenarios, %

Source: Battisti et al. (2014), Table 7.

We calibrate our model to match the empirical moments for the 20 OECD countries shown in Table 1. Besides the relative labour market performance of immigrants, we also match facts on public spending, letting the government finance public goods and unemployment benefits by proportional taxation. We also match GDP per capita and average job durations for both educational groups.

Figure 1 presents results from two main scenarios. In the first, we calculate the difference in welfare (which can be also thought of as the difference in real post-tax income) between the status quo observed in 2011 and a hypothetical situation with no immigrants (closed borders). We find that the native welfare gains from immigration are positive in 19 out of 20 countries. In all countries but Switzerland (where the effect is essentially zero) natives have, on average, gained from immigration, and sometimes the gain is rather large (up to 2% of after-tax income). In the second scenario, we compute the difference in welfare of natives between the status quo in 2011 and a hypothetical situation in which the immigrant share had been kept at the level of 2000. We find a positive gain from this recent immigration in 16 countries.

In 14 out of 20 cases, the existing stock of immigrants makes both skill-groups of natives (college and non-college educated) better off. In the canonical model without labour market imperfections, these Pareto gains would be impossible. Moreover, even incumbent immigrants are found to be better off with immigration. Again, in the canonical framework this is extremely unlikely, as new immigrants are more closely substitutable with incumbent immigrants than with natives. The reason for these somewhat surprising results is the job-creation effect described above. Namely, immigration can grease the wheels of the labour market by affecting job creation incentives.

What explains the cross-country heterogeneity in benefits?

The comparative statics from our analysis reveal that the following country characteristics increase the native immigration gains from a one-percentage-point increase in the immigrant labour force share:

(i) Higher native–immigrant wage gaps, regardless of the skill group;

(ii) A lower native–immigrant unemployment gap for the low-skilled;

(iii) More generous unemployment insurance;

(iv) A higher share of tertiary-educated workers amongst immigrants;

(v) Lower government expenditures.

The intuition is as follows. Lower bargaining power for immigrants implies that they have lower wages, and this encourages firms to create more jobs. Also, lower job-destruction rates for immigrants make hiring an immigrant more valuable for firms and encourage firms to create more jobs. A more generous unemployment insurance system makes immigration more beneficial for natives because higher unemployment benefits reduce job creation, and immigration helps to alleviate this distortion. In other words, the greasing-the-wheels effect and its lowering of the unemployment rate are particularly valuable when distortions are large. A higher share of tertiary-educated immigrants and lower government expenditures increase the benefits because they lower the extent of redistribution from natives to migrants.

Conclusions

Our analysis shows that immigration into imperfectly competitive labour markets need not be worsening labour market outcomes for natives. Instead, it can improve the job creation incentives of firms. Thus, measures that aim at eliminating the immigrant–native wage gap may hurt natives. This positive effect is threatened if immigrants are too often unemployed or if too many of them are unskilled. Policies reducing the rate of job loss for immigrants would therefore help natives. Finally, in contrast to widespread belief, immigrants do not seem to hurt low-skilled natives, even in the more realistic framework developed here. This is because immigration is often balanced between more and less educated, because its job-creation effect can help, and because redistribution towards immigrants is not as large as often suggested in the debate.

References

Battisti, M, G Felbermayr, G Peri, and P Poutvaara (2014), “Immigration, Search, and Redistribution: A Quantitative Assessment of Native Welfare”, NBER Working Paper 20131.

Boeri, T (2010), “Immigration to the Land of Redistribution”, Economica, 77(308): 651–687.

Borjas, G J (1995), “The Economic Benefits from Immigration”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(2): 3–22.

Borjas, G J (2003), “The Labor Demand Curve is Downward Sloping: Reexamining the Impact of Immigration on the Labor Market”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(4): 1335–1374.

D’Amuri, F, G Ottaviano, and G Peri (2010), “The Labor Market Impact of Immigration in Western Germany in the 1990s”, European Economic Review, 54(4): 550–570.

Dustmann, C and T Frattini (2013), “The Fiscal Effects of Immigration to the UK”, CreAM Discussion Paper 22/13.

Hanson, G H (2009), “The Economic Consequences of the International Migration of Labor”, Annual Review of Economics, 1(1): 179–208.

Ottaviano, G I P and G Peri (2008), “Immigration in Western Europe”, VoxEU.org, 17 April.