There is a curious difference between how foreign and local economists see the wisdom of capital controls in Iceland. In a recent IMF-government of Iceland conference1, two Nobel Prize winners in economics, along with senior IMF representatives, expressed strong support for the capital controls. The Icelandic economists addressing the conference were not as enthusiastic.

What accounts for this difference? The foreign economists seem to be poorly informed about the actual form and implementation of the Icelandic capital controls. This, however, does not prevent them from influencing economic policy in Iceland.

The capital controls the foreign economists seem to have in mind are some sort of short-term prevention of hot money flows. The reality is different. The actual controls are much closer to the 1950s style of capital controls, with virtually all currency transactions requiring permission from the Central Bank.

Icelandic firms seeking to invest abroad need rarely-granted permission from the Central Bank. Icelandic citizens need a government authorisation for foreign travel, since a Central Bank licence is needed to get tightly rationed foreign currency for travel. Any individual seeking to emigrate from Iceland is at least partially locked in by the capital controls by virtue of not being able to transfer his or her assets abroad, a restriction on emigration not commonly seen in democracies. This disregard of individuals’ civil rights as a result of the capital controls violates Iceland’s legal commitments under the European four freedoms.

The motivating problem

One of the key factors in Iceland’s financial collapse in October 2008 (see my Vox article, Danielsson 2008) was substantial inflows of speculative capital leading to significant currency overvaluation, causing a trade deficit and the accumulation of foreign currency debt.

Immediately following the crisis, the foreign part of the payment system collapsed, and the exchange rate fell by around 25%. Funds held by carry traders amounted to over 40% of GDP, and it was feared that the bulk of those investors, along with some domestic agents, would seek to leave the Icelandic currency, exaggerating the fall in the exchange rate.

Under these circumstances, the government had three choices.

- Let the currency markets determine the exchange rate and face the consequences;

- manage exchange rates by imposing special taxes on speculative capital movements; or

- impose capital controls.

Neither the Icelandic policymakers nor the IMF found the first choice palatable.

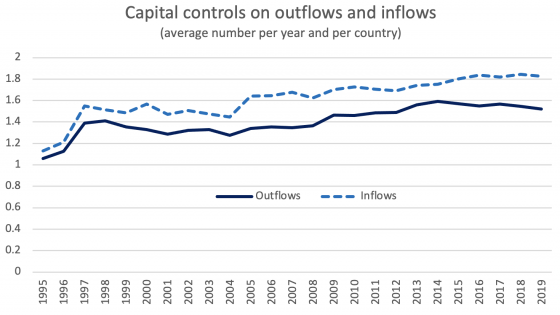

The Icelandic authorities seem to have been in favour of the second choice but reportedly the IMF, arguing in terms of equal treatment of all foreign currency transactions, demanded strict capital controls. So, at the IMF’s insistence, all-encompassing capital controls applying both to inflows and outflows of currency were introduced.

The cost of capital controls

Capital controls distort the price of capital leading to deadweight loss – amounting to up to 1% of GDP per year in Iceland. The longer-run consequences of the capital controls are the weakening of the competitive position of Icelandic industries and a distortion of the structure of domestic industries due to the adjustment to long-term false prices of foreign currency and the presence of capital controls. Both distortions involve structural adjustments that will take considerable time and expense to unwind once the capital controls are lifted.

The capital controls erode the trust of both domestic and foreign investors in the Icelandic economy, resulting in a significant risk premium added to loans and investments. Thus, the capital controls do not only undermine the long-term health of the Icelandic economy, in the long run they also undermine their own objective of maintaining the exchange rate.

Finally, the capital controls transfer significant new powers to the government, enabling it to implement industrial policy whilst conferring favours to those favoured by exemptions, leading to rent seeking and associated distortions. Even if the application of the controls were to be totally devoid of political favouritism and political ideology, the possibility of misuse inevitably generates suspicion, undermining trust and cohesion in society.

Why the IMF change of heart?

Why did the IMF in this case abandon its long-standing role in promoting free capital markets? We can only hypothesise, but three alternatives come to mind.

- First, the IMF may not in 2008 have had the economic understanding, knowledge, and speed of reaction to make real-time policy decisions during crises in modern developed economies.

After all, the last time a similarly developed economy requested IMF aid was the UK in 1976. The IMF’s experience in non-democratic less-developed economies may have suggested to it that strict 1950s style capital controls are useful, and the Fund may not have appreciated the adverse general equilibrium consequences in a highly developed economy integrated into the North European economic zone, nor the resulting violations of civil rights.

- Second, the policy adopted for Iceland might represent a genuine policy shift by the IMF.

This certainly is the impression given by the Fund in its write-up of the conference, statements by an IMF Deputy Managing Director in the conference, and the Fund’s enthusiastic embracement of “Unorthodox Policies” (IMF 2011). The Fund may have come to the conclusion that the Washington consensus has failed, and that financial crises are caused by free financial markets, with extensive direct government intervention in markets the answer.

- Third, it is possible that the IMF, following careful consideration, concluded that capital controls were nevertheless the least bad policy response given the specific Icelandic economic and political context.

This would imply that its imposition of the Icelandic capital controls was a one-off event not to be repeated elsewhere.

Conclusion

Iceland was faced with a serious problem of hot money overhang following its crisis in 2008 and it was feared that speculators would head for the exits, causing an uncontrolled collapse in the exchange rate. In our view, this fear was unfounded. Any speculator exiting under those circumstances would have faced significant losses compared with the option of waiting for economic stabilisation and the consequent currency appreciation. After all, the currency approximately reached its long-term equilibrium rate immediately after the collapse.

Thus, in our view, the imposition of capital controls was both unnecessary and unjustified. Without them, the exchange rate might have temporarily fallen even further in a worst case scenario, in which case a surgical intervention in the form of a temporary tax on short capital outflows would have been a sufficient policy response.

Instead, the IMF forced the Icelandic government to impose draconian capital controls of a type last seen in developed economies in the 1950s, causing significant short-term and long-term economic damage. The capital controls were initially touted as a temporary measure, but now three years after the event it looks like they are there to stay, and as the domestic economy adapts to their presence, they will be increasingly costly to abolish. After all, the last time Iceland imposed capital controls in the 1930s, they lasted until 1993.

The capital controls have resulted in an intrusive licensing regime, with government permission required for foreign travel and those emigrating prevented from taking their assets with them. Both are direct violations of the civil rights of Icelandic citizens and Iceland’s international commitments as a democratic European country.

Our hope is that other countries facing a similar situation will have the good fortune of receiving better advice from the IMF.

References

Danielsson, Jon (2008), “The first casualty of the crisis: Iceland”, VoxEU.org, 12 November.

IMF (2011), “Iceland's Unorthodox Policies Suggest Alternative Way Out of Crisis”, IMF Survey Online, 3 November.

1 See video here.