Basic scientific research infrastructure – such as CERN’s Large Hadron Collider, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), or the Super-Kamiokande neutrino observatory, which have all enabled Nobel prize-winning scientific breakthroughs – require large-scale (and increasing, see Bloom et al. 2017) investments in a single or a few geographical locations. In a recent study (Helmers and Overman 2017), we analyse the impact of such large facilities on where scientific research is conducted.

Specifically, we examine the impact of the UK’s Diamond Light Source, a third-generation synchrotron and the largest single investment in basic research infrastructure in the modern history of the UK – on the distribution of the scientific research enabled by the facility.

Our findings suggest that big scientific research facilities like the Diamond Light Source benefit scientists in their direct geographical proximity significantly more than scientists located further away. Perhaps more surprisingly, the highly localised effects of scientific infrastructure on research productivity extend even to scientists that do not rely on the facilities directly for their work.

Since scientific facilities often cannot be distributed across multiple locations, these findings suggest that the decision on where to locate a facility has important consequences on the geographical distribution of scientific research. Large-scale scientific facilities have the power to create new and highly concentrated geographical clusters of scientific research as well as reinforcing existing clusters in proximity to the infrastructure.

Our results therefore offer evidence on the importance of agglomeration externalities produced by indivisible scientific research facilities for science and innovation. This adds evidence to the existing literature that focuses on externalities between companies (Jaffe et al. 1993, Audretsch and Feldman 1996) or from university to private industry (Jaffe 1989, Kantor and Whalley 2014a, 2014b).

Quantifying the impact of large-scale scientific infrastructure is generally difficult because the location for the investment is not chosen at random. Instead, policymakers, just like private companies, strategically place the facility often in an existing scientific hub (in the case of Diamond, the Harwell Science and Innovation Campus at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory near Oxford.

This then poses the research challenge of how to separate the effects of the existing cluster from any additional effects created by the new facility. We overcome this difficulty by capitalising on the controversy that existed in 1998 about where the Diamond Light Source should be sited – and in particular, the existence of a ’runner-up’ location at the Daresbury Science and Innovation Campus in Cheshire.

The government initially planned to build the new facility at Daresbury, which was also home to Diamond’s predecessor, the Synchrotron Radiation Source. Effective lobbying led to a change of heart – and a final decision in 2000 to locate the new facility at Harwell. This sparked fierce controversy because of the longstanding debate on the north-south divide in scientific research investment in the UK.

Our study analyses how scientific research in the form of journal publications was affected by Diamond’s opening in January 2007. A comparison of papers produced by researchers near Diamond to those near Daresbury shows that output from researchers in direct proximity to the synchrotron increased more than it would have done if the facility had been located elsewhere.

We find that scientists located within a 25km radius of Diamond produced around 11% more scientific articles over the 2000-2010 period as a result of their geographical proximity to the facility. This is the combined result of two effects, one direct and one indirect.

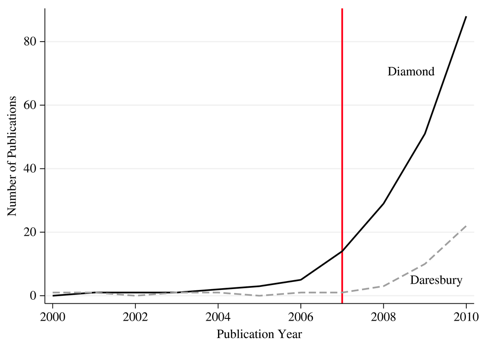

The direct effect results simply from ease of access for nearby researchers who use the synchrotron. The indirect effect is perhaps more surprising. There is also an increase in scientific papers even when that research made no direct use of Diamond. Figure 1 shows the number of these articles before and after Diamond opened written by scientists within 25km of Diamond and the runner-up location at Daresbury. The most likely explanation is that these indirect affects arise as a result of the localised knowledge spillovers that occur when researchers learn from each other, for example, through personal contact.

Figure 1 Number of articles related to research conducted at Diamond within 25km distance ring of Diamond and Daresbury, before and after 2007

We investigated whether the direct and indirect effects are driven by increases in inputs or productivity and found that the effects are mainly driven by an increase in inputs – the number of scientists working in geographical proximity to the facility. The results indicate that the increase comes from new scientists rather than the relocation of existing scientists.

In the case of the Diamond synchrotron, locating the particle accelerator close to Oxford reinforced the scientific strength of the so-called Golden Triangle of London, Oxford, and Cambridge. Because clusters tend to create self-reinforcing feedback loops that attract more private and public investment, the results of the study are likely to underestimate the long-run impact of the synchrotron on the geographical location of scientific research in the UK.

References

Audretsch, D B, and M P Feldman (1996), “R&D spillovers and the geography of innovation and production”, American Economic Review, 86 (3), 630–40.

Bloom, N, C Jones, J Van Reenen, and M Webb (2017), “Ideas aren’t running out, but they are getting more expensive to find”, VoxEU.org, 20 September.

Helmers C, and H Overman (2017), “My precious! The location and diffusion of scientific research: evidence from the Synchrotron Diamond Light Source”, Economic Journal, 127 (604).

Jaffe, A (1989), “Real effects of academic research”, American Economic Review, 79 (5), 957–70.

Jaffe, A, M Trajtenberg, and R Henderson (1993), “Geographic localization of knowledge spillovers as evidenced by patent citations”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108 (3), 577–98.

Kantor, S, and A Whalley (2014a), “Knowledge spillovers from research universities: Evidence from endowment value shocks”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 96 (1), 171–88.

Kantor, S, and A Whalley (2014b), “Research proximity and productivity: long-term evidence from agriculture”, mimeo., Economics Department, University of California-Merced.