Few topics in economics are so central and yet generate so much controversy as discounting. Cost-benefit analyses of long-lived public projects rely heavily on social discounting, especially in the areas of environmental protection, infrastructure, education, and health. Most regulatory agencies have procedures for discounting future benefits and costs. However, economists continue to debate what constitutes an appropriate discount rate and, even more fundamentally, how discounting should be applied. The potential consequences of these debates are significant. Small changes in discounting procedures can have a large influence on present value calculations of long-lived projects, with a direct impact on policy evaluation. For example, increasing the discount rate from 3% to 4% can cut the value of benefits received in 70 years by half.

Climate changes the debate

Economic analysis of climate change has elevated the stakes for the discounting debate. Whether a more or less aggressive climate policy passes a cost-benefit test depends critically on the social discount rate. This is the central insight of the highly influential and contrasting contributions of Nicholas Stern (2007) and William Nordhaus (2007). Both employ a standard framework for discounting within integrated assessment models (IAMs) of climate change. They differ, however, in their underlying assumptions about an important component of the standard Ramsey (1928) social discount rate formula – the utility discount rate (UDR). The UDR represents the rate of time preference that policymakers use between time periods irrespective of differences in consumption. The rate of time preference may come from ethical arguments or attempts to represent the population impacted by the policy.

Stern uses a very low UDR and as a result supports more aggressive climate policy compared to Nordhaus. Stern follows classical economists. He argues that the choice of a UDR should be based on ethical considerations. Indeed, some economists have argued that the only reason for the UDR to exceed zero is because of catastrophic risk to the world (Goulder and Williams 2012). By contrast, Nordhaus argues that discounting should be consistent with behaviour reflected in observable market interest rates. The Stern-Nordhaus exchange rekindled a long-standing debate about ‘prescriptive’ versus ‘descriptive’ approaches to discounting.

Despite the debate, there remains relatively little empirical guidance on how to choose the discount rate, especially with regard to the underlying UDR. As a result, researchers and policymakers are often left to choose either reliance on some ethical or normative criteria, many of which can push in opposite directions, or to back out values after calibrating on more observable parameters, including a priori assumptions about what the overall social discount rate should be. The current state of affairs is particularly unsatisfactory because the choice between a prescriptive versus descriptive approach generally is not separable from whether one thinks the discount rate should be low or high.

A mortality-based alternative

We have developed an alternative demographic approach for estimating the UDR that serves as a useful benchmark (Fenichel et al. 2017). We begin by asking how would an individual value the future if the only reason for valuing it less than the present were the chance that the individual would not survive to enjoy the future. Then, we recognise that multiple generations are extant in a population at any point in time and argue that the UDR can reflect an aggregation over how individuals in these generations care about their own future utility.

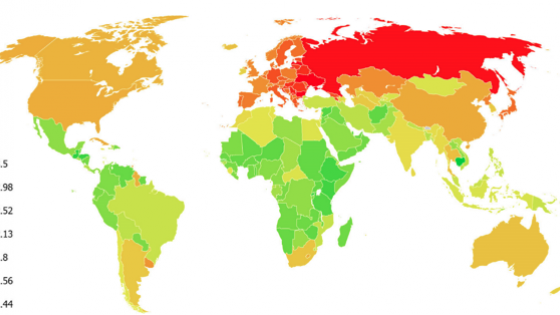

We use country-specific life tables from the World Health Organization to derive estimates of a mean and median social UDR based on the age structure of a population and life expectancy at each age for most countries in the world (Figure 1). Given actual life expectancies, the estimates inform periods considered long-term for many policies (e.g. 50 to 80 years). Our estimates can apply even further into the future to the extent that population structures are stable, for which we find empirical support on the scale of decades.

Figure 1 Estimates of the mean utility discount rates across countries in 2012

While there is considerable heterogeneity across countries, our UDR estimates fall within the range economists employ and consider reasonable. The approach yields global estimates of the UDR at 1.3% or 2.1% when the UDR matches that of the median or mean individual’s preferences, respectively. We also show how countries can have similar estimates of the UDR for very different reasons. There are two demographic effects, namely age distribution and life expectancy. A younger age structure and longer life expectancy will tend to decrease a country's UDR, because more years expected to live will cause individuals to discount the future less. However, for most countries these effects work against each other with long lived countries generally having an older age structure and vice-versa.

The role of discount rates heterogeneity in climate policy

To examine the role of UDR heterogeneity in the economics of climate change, we use the Regional Integrated Climate-Economy (RICE) model (Nordhaus 2010) and our method for measuring UDRs. We compare the default case where all 12 RICE regions share the same global estimate of the UDR to a case where each region has its own estimate of the UDR.

Introducing heterogeneity has little effect on the business-as-usual trajectory of emissions. It does, however, have a meaningful effect on the efficient trajectory of emissions. We find that adding the UDR heterogeneity results in an efficient carbon tax that is 28% greater by the end of the century, relative to the case where all regions have the same UDR. Underlying the aggregate effects is a shift among countries so that those regions with lower UDRs than the world-average reduce emissions more. Not only does a lower UDR impose greater concern for future climate damages, as is often noted in the literature, it also increases a country’s concern about future production. That concern leads low UDR regions to increase emissions through greater savings, capital accumulation, and output. As a consequence, regions with lower UDRs (e.g. Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America) would be responsible for relatively greater emission reductions, whereas those with greater UDRs (e.g. Japan, Eurasia, and Russia) would be responsible for relatively fewer. This could have important implications for understanding burden sharing across countries and their willingness to participate in international climate agreements.

Implications for the study of discounting

We are aware that a leading criticism of our approach is that focusing only on mortality risk oversimplifies the basis for individual pure rates of time preference. Yet we contend that arguments can be made that the approach provides either over- or underestimates. The fact that individuals are well-known to be impatient even without mortality risk suggests a greater UDR. In contrast, the presence of bequest motives for future generations implies a smaller UDR. The advantage of a purely mortality-based approach is transparency, an empirical basis, and broad data availability – that is, the mortality-based approach gives a non-arbitrary starting point for further adjustments. A further advantage of our approach is that it facilitates transparency with respect to decisions about how different generations are actually weighted.

Discounting is central to many important policy decisions, and a demographically based approach can serve as a useful point of comparison. From an analytical perspective, the starting point of our analysis is recognition that even a representative agent must die. We show how age-specific mortality rates and life expectancy imply a natural UDR for individuals at each age in a population. This part of the analysis is descriptive. The part where individual UDRs are aggregated to the population level is necessarily prescriptive because it implies weights among those currently alive.

References

Fenichel, E P, M J Kotchen, and E T Addicott (2017), “Even the representative agent must die: Using demographics to inform long-term social discount rates”, NBER Working Paper 23591.

Goulder, L H, and R C III Williams (2012), The choice of discount rate for climate change policy evaluation, Washington DC: Resources for the Future.

Nordhaus, W D (2007), “A review of the Stern Review on the economics of climate change”, Journal of Economic Literature, 45 (3), 686-702.

Nordhaus, W D (2010), “Economic aspects of global warming in a post-Copenhagen environment”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107 (26), 11721-11726.

Ramsey, F P (1928), “A mathematical theory of saving”, The Economic Journal, 38 (152), 543-559.

Stern, N (2007), The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review, New York: Cambridge University Press.