The recent Global Crisis has revealed financial market integration to be the major culprit for the large and fast diffusion of shocks across borders. In an influential paper, Rey (2013) describes the presence of a global financial cycle, where an “international credit channel” enables financial conditions to propagate across borders. While cycles are unambiguously synchronised between trade partners, there is less agreement about the role played by greater financial integration.

Theory is an imperfect guide. In a two-country real business cycles model, a country-specific productivity shock – which creates a disparity between the return to investment across countries – makes capital flow wherever returns are higher (to ‘make hay where the sun shines’). So greater financial integration lowers the international synchronisation of business cycles (Backus and 1992). But in a similar two-country model augmented with credit or collateral constraints, a country-specific shock that makes the constraint bind at home is contagious abroad, as domestic agents recall foreign assets to meet their constraint (Devereux and Yetman 2010, Kalemli-Ozcan 2013, Allen and Gale 2000). So, greater financial linkages can increase the international synchronisation of business cycles.

One common feature of these models is that they analyse the consequences of purely ‘idiosyncratic’ (i.e. country-specific) shocks. But they are silent about what happens to business cycle synchronisation in the face of ‘common shocks’. In a recent paper (Cesa‐Bianchi et al. 2016), we show that accounting for common shocks – and their heterogeneous effects across countries – has first-order consequences on the estimated impact of financial integration on business cycle synchronisation.1

On the one hand, we show that capital tends to flow between the same pairs of countries in the face of common shocks. In response to positive shocks, capital tends to flow from countries that are relatively unresponsive (or ‘inelastic’) to common shocks to countries that are relatively responsive (or ‘elastic’) to common shocks. The opposite happens in response to negative common shocks. This generates a divergence in their business cycles, implying that financial flows do not help ‘make hay where the sun shines’. On the other hand, we document a positive association between business cycle synchronisation and financial linkages in response to idiosyncratic shocks.

Measuring business cycle synchronisation: The role of common and idiosyncratic shocks

A standard and simple measure of cross-country business cycle synchronisation is the opposite of the pairwise difference in annual GDP growth rates (in absolute value). This variable, labelled S, is intuitive – it takes negative values, increasing with the degree of synchronisation between a pair of countries, and reaching an upper bound at zero for perfectly synchronised countries.2 Figure 1 reports the behaviour of S in the cross-section of 18 advanced economies from 1980 to 2012.

Figure 1. A simple measure of cross-country business cycle synchronisation

Note. The solid line plots the evolution over time of the average value of S for the 1980-2012 period. The average is computed across 153 country pairs (our sample spans 18 countries) for each year.

Figure 1 reveals a somewhat counterintuitive fact – the standard measure of synchronisation, S, falls in 1991, when there was a recession in a number of advanced economies. And it falls sharply again during the Global Crisis.

This is due to the fact that the simple measure S does not take into account that:

- GDP growth rates respond to both country-specific shocks as well as common shocks; and

- Common shocks have heterogeneous effects across countries.3

In other words, even though GDP growth rates were falling in most countries during Global Crisis, the differential pace of contraction across countries shows up in S as a fall in synchronisation. For example, US annual GDP growth went from about -0.3 in 2008 to about -2.8% in 2009, whereas UK GDP growth went from -0.3 to -4.3%. As a result, the synchronisation measure S fell from 0 to -1.5.

To address this, we decompose country-specific GDP growth rates into a common and an idiosyncratic component. To identify common shocks and their heterogeneous effects across countries, we use principal components techniques that allow country-specific loadings on the factors.

This decomposition also allows us to decompose the traditional measure of business cycle synchronisation into two elements: a synchronisation measure that is based on the pairwise difference of GDP’s response to idiosyncratic shocks (Sɛ), and a synchronisation measure that is based on the pairwise difference of GDP’s response to common shocks (SF). We report this decomposition, together with the original measure S, in Figure 2.

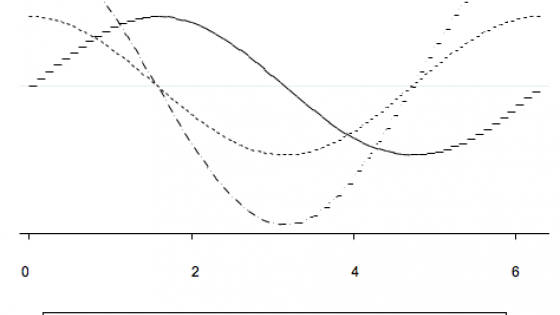

Figure 2. The conventional measure of cross-country business cycle synchronisation and its decomposition in idiosyncratic and common components

Note. The solid line plots the evolution over time of the average value of S for the 1980-2012 period. The chart also reports the cross-sectional averages of the idiosyncratic component (Sɛ, dashed line) and the common component (SF, dotted line) of S. The average is computed across 153 country pairs (our sample spans 18 countries) for each year.

Figure 2 confirms our above conjecture, showing that the decline in S observed during the 1991 or 2008 recessions is clearly associated with common shocks, as SF drops substantially in both cases. In contrast, Sɛ increases in 2008, and does not fall in 1991. This suggests the measure S conflates two mechanisms: the international propagation of idiosyncratic shocks, Sɛ, and the international equilibrium response to common shocks, SF. The former is a measure of co-movement across countries; the latter is a measure of the dispersion in GDP growth rates in response to common shocks. The presence of these two elements needs to be taken into account by empirical work that tries to estimate the effect of finance on synchronisation.

Reinterpreting the evidence

Armed with the above decomposition, we revisit the evidence of the impact of finance on synchronisation. Our approach builds on the conventional in the literature (see Kalemli-Ozcan et al. 2013) – we regress business cycle synchronisation on the intensity of bilateral bank linkages (using BIS Locational Banking Statistics).

We run regressions using the three measures of synchronisation described above, namely, S, SF, and Sɛ. The standard measure of synchronisation, S, implies the well-known result that increased financial linkages lower business cycle synchronisation, a finding that jars with what was observed during the global financial crisis.

We then show that this same result holds when using SF, i.e. when synchronisation is conditioned on common shocks only. The result comes from permanent differences across countries in terms of how growth and capital flows respond to common shocks.

What happens when we use Sɛ? This synchronisation measure should capture the equilibrium response of GDP to country-specific shocks, i.e. the object of interest of most international business cycle models. We find that, in response to idiosyncratic shocks, increased financial integration increases business cycle synchronisation.

Conclusion

Do more financially integrated economies have more synchronised business cycles? The answer crucially depends on the source of the shock. Using a sample of advanced economies, we find that the answer is “yes” if we use a synchronisation measure that strips out the heterogeneous responses of GDP to common shocks. Differently in response to common shocks, financial flows seem to respond to ‘safe haven’ motives, flowing systematically between the same economies and lowering their business cycle synchronisation.

Our result points to the crucial role played by financial frictions in the international transmission of shocks, even in ‘tranquil’ times. While in a frictionless world financial integration allows perfect risk sharing, when financial frictions are at work a strategic trade-off between openness and stability may emerge.

References

Allen, F, and D Gale (2000), “Financial Contagion,” Journal of Political Economy 108(1): 1–33.

Backus, D K, P J Kehoe, and F E Kydland (1992), “International Real Business Cycles”, Journal of Political Economy 100(4): 745–75.

Cesa‐Bianchi, A, J Imbs, and J Saleheen (2016), “Finance and Synchronization”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 11037.

Corsetti, G, M Pericoli, and M Sbracia (2005), “’Some contagion, some interdependence’: More pitfalls in tests of financial contagion,” Journal of International Money and Finance 24(8): 1177–1199.

Crucini, M, A Kose, and C Otrok (2011), “What are the driving forces of international business cycles?,” Review of Economic Dynamics 14(1), 156–175.

Devereux, M B, and J Yetman (2010), “Leverage Constraints and the International Transmission of Shocks,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 42(s1): 71–105.

Forbes, K J, and R Rigobon (2002), “No Contagion, Only Interdependence: Measuring Stock Market Comovements,” Journal of Finance 57(5): 2223–2261.

Forni, M, and L Reichlin (1998), “Let’s Get Real: A Factor Analytical Approach to Disaggregated Business Cycle Dynamics,” Review of Economic Studies 65(3): 453–73.

Giannone, D, M Lenza, and L Reichlin (2010), “Business Cycles in the Euro Area,” in Europe and the Euro, NBER Chapters, pp. 141–167, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Kalemli-Ozcan, S, E Papaioannou, and F Perri (2013), “Global banks and crisis transmission,” Journal of International Economics 89(2): 495–510.

Kalemli-Ozcan, S, E Papaioannou, and J-L Peydro (2013), “Financial Regulation, Financial Globalization, and the Synchronization of Economic Activity,” Journal of Finance 68(3): 1179–1228.

Kose, M A, C Otrok, and C H Whiteman (2003), “International Business Cycles: World, Region, and Country-Specific Factors,” American Economic Review 93(4): 1216–1239.

Kose, A, C Otrok, and C H Whiteman (2008), “Understanding the evolution of world business cycles,” Journal of International Economics 75(1): 110–130.

Mumtaz, H, S Simonelli, and P Surico (2011), “International Comovements, Business Cycle and Inflation: a Historical Perspective,” Review of Economic Dynamics 14(1): 176–198.

Rey, H (2013), “Dilemma not trilemma: the global cycle and monetary policy independence,” Proceedings -Economic Policy Symposium -Jackson Hole, pp. 1–2.

Endnotes

1 It is well known that the bulk of the volatility in GDP across countries can be explained by common shocks (Kose et al. 2003, Kose et al. 2008, and Crucini et al. 2011). Moreover, the possibility that common shocks have heterogeneous loadings is an old tradition in empirical macroeconomics (see Forni and Reichlin 1998, Bernanke et al. 2005; and Mumtaz et al. 2011).

2 The measure presents two key advantages – first it is readily observable at yearly frequency. Second, unlike the Pearson correlation coefficient, it is invariant to the volatility of the underlying shock, see Forbes and Rigobon (2001), Corsetti et al. (2002). Moreover, it is now used widely, by Giannone et al. (2010), Kalemli-Ozcan et al. (2013) Kalemli-Ozcan et al. (2013), among others.

3 There are ample intuitive reasons for why common shocks can have heterogeneous effects across countries, for instance because they have more flexible labour and or product markets.