In a recent Vox column, Auer and Kraenzlin (2009) pointed out that the world’s major central banks used swap agreement to address mismatches in their currency-specific liquidity needs during the recent global crisis – measures that were highly effective and came at a very low cost. Their report focused on the swap lines instrumented by the Swiss National Bank and the ECB. In Aizenman et al. (2010), we analyse the provision of these swap lines by all the major suppliers (US Fed, ECB, and the Bank of China), studying the possible impact of swap lines on the future demand for international reserves by developing and emerging market countries.

While we share Auer and Kraenzlin’s assessment of the efficacy of these swap arrangements, we conclude that selectivity of the swap lines indicates that only countries with significant trade and financial linkages can expect access to such ad hoc arrangements, on a case by case basis. Moral hazard concerns suggest that the applicability of these arrangements will remain limited. However, deepening swap agreements and regional reserve pooling arrangements may weaken the precautionary motive for reserve accumulation.

Empirical analysis of swap lines

The swap lines since December 2007 to date involve 24 countries, as shown in Table 1. The US Federal Reserve has been the largest provider, extending 14 swap lines, $755 billion in total. The Bank of China has provided swap lines to 6 countries (650 billion Yuan) and the ECB commits 4 swap lines (€31.5 billion). While the swap lines provided by the Federal Reserve to the ECB, the Bank of Japan, and the Bank of England are by far the largest, many believe that the swap commitments among these central banks could be even larger. Better institutional quality means lower moral hazard which should imply more elastic access to larger swap lines, which seems to be the case for the swap lines between the OECD countries.1

Table 1. The initial swap lines provided by the US Federal Reserve, the ECB and the People Bank of China (billions).

|

Country

|

FED_USD

|

ECB_EURO

|

PBC_CNY

|

|

Argentina

|

|

|

70

|

|

Australia

|

30

|

|

|

|

Brazil

|

30

|

|

|

|

Belarus

|

|

|

20

|

|

Canada

|

30

|

|

|

|

Denmark

|

15

|

15

|

|

|

ECB

|

240

|

|

|

|

Hong Kong

|

|

|

200

|

|

Hungary

|

|

5

|

|

|

Iceland

|

|

1.5

|

|

|

Indonesia

|

|

|

100

|

|

Japan

|

120

|

|

|

|

Korea

|

30

|

|

180

|

|

Mexico

|

30

|

|

|

|

Malaysia

|

|

|

80

|

|

Norway

|

15

|

|

|

|

New Zealand

|

15

|

|

|

|

Poland

|

|

10

|

|

|

Sweden

|

30

|

|

|

|

Singapore

|

30

|

|

|

|

Switzerland

|

60

|

|

|

|

UK

|

80

|

|

|

A crucial stylised fact has been the unprecedented proliferation of swap agreements between large central banks on one hand and the central banks of emerging markets on the other. The most well-known of such agreements is the $30 billion agreements between the US Fed and the central banks of four systematically important emerging markets with strong fundamentals – Brazil, Korea, Mexico and Singapore – which came into effect in October 2008. As noted by Aizenman and Pasricha (2010), exposure of US banks was the single most important explanation for why the US selected to swap deals with the “chosen four.”

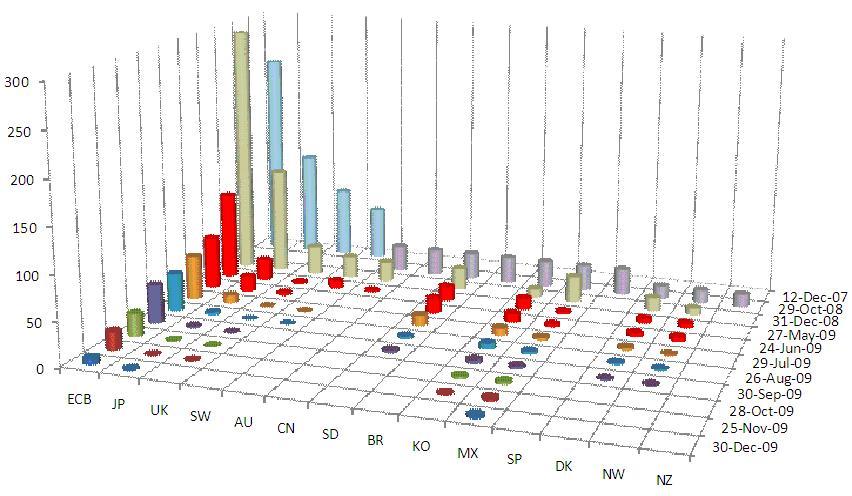

Figure 1 plots the extent and the use of US Fed swap lines in the last two years. The earliest columns measure the size of the swap lines. The remaining columns correspond to the actual use of the swap lines (subject to data availability). The figure reveals that use of the Federal Reserve’s dollar swaps has been limited. Since the announcements of dollar swap liquidity, the amounts outstanding have declined across the swap receivers. Canada, Brazil, Singapore, and New Zealand have never used the dollar swaps.

Figure 1. Outstanding swap lines between the US Federal Reserve and foreign central banks

Source: Federal Reserve System Monthly Report on Credit and Liquidity Programs and the Balance Sheet.

Note: The authorised dates of these dollar swap liquidity are December 12, 2007 for the ECB and the Swiss National Bank, and 29 October 2008 for the other central banks (except the Bank of England and the Bank of Japan, where the dollar swaps are implicitly always in place). The earliest columns measure the size of the swap lines.

The evidence suggests that the swap receivers were more exposed to the (lagged) effects of a general deterioration of conditions in global short-term funding markets, and deleveraging pressures. Obstfeld et al. (2009) find that currencies of countries holding more reserves relative to M2 have tended to appreciate in the crisis, whereas those with smaller foreign reserves have depreciated. They also argue that the dollar swaps to the emerging markets have been largely symbolic since Brazil, Korea, and Singapore already had foreign reserves more than predicted.

Our evidence suggests that, as a group, the emerging market swap recipients have experienced significantly larger nominal currency depreciation and reduction of short-term debt stocks. Given that most of the short-term external debts in emerging market countries are denominated in foreign currencies, the swap liquidity might have been in place to backstopping these emerging markets, substituting for a large hoarding of foreign exchange reserves in a short period of time. Indeed, one may argue that in the presence of market panics, the sheer provision of swap lines may prevent multiple equilibria, selecting the “no-run” equilibrium (see the experience of Korea, overviewed in our paper). Hence, swap lines may stabilise market conditions even if they are not used.

There is also a noticeable decline in export credits of developing countries – probably reflecting the effects of adverse global short-term credit market conditions on the real side of global economy, namely international trade in goods and services. For all the emerging markets, export credits account for 10% of the short-term external debts. Our results show that great importance of swap recipients as an export destination is associated with a larger amount of swap liquidity extended from the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of China. For the swap liquidity extended by the Bank of China, the association between the swap size and export share is quite systematic.. Hong Kong, Korea, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Argentina account for 12%, 4%, 0.9%, 1.1% and 0.2% of China’s total exports, respectively. Larger export destinations tend to receive larger swap lines – this is also the case for the US.

The results are consistent with the possibility that the introduction of swap lines is more important than the actual use of these lines. Yet, the actual use of a swap line may be associated with a stigma, implying that countries would prefer to delay to use of swap line as a last resort (or at least as a secondary resort). Hence, somewhat paradoxically, countries that are eager to have access to swap lines in a crisis may prefer to refrain from using them.

Concluding observations

Upon closer inspection, there are clear limits to substitutability between swaps and reserves. By and large swap lines are extended only to fundamentally sound and well-managed emerging markets, and to important trade partners. Crucially, sound fundamentals include healthy levels of foreign-exchange reserves. The highly selective nature of swap recipients means that a majority of developing countries will not have access to swap facilities. While swaps can contribute to the global public good of global financial stability, in fact large central banks provide liquidity support only when it is in the self-interest of their respective countries to do so. The inclusion of countries such as Argentina and Belarus – not known for strong fundamentals or sound management – among the Bank of China’s swap recipient countries points to the overarching dominance of export markets as the key criterion. Following from this, the growth of yuan-dominated swap lines may be a precursor to the eventual emergence of the yuan as a new reserve currency.

When market confidence is shattered, foreign-exchange market intervention to stabilise exchange rate becomes ineffective, even if the economy has sound fundamentals. That is, reserves fail to perform their precautionary or self-insurance function when the unlikely becomes the reality. In fact, in the case of Korea, declining reserves themselves intensified market fears and concerns, forming a vicious cycle in which adverse market sentiment drives down reserves via foreign-exchange market intervention, and the decline in reserves, in turn, further dampens market sentiment. The timing of market movements suggests that the Bank of Korea's three swap agreements, in particular the agreement with the US Fed, played a pivotal role in calming down the growing market hysteria over a possible dollar shortage.

A puzzle is the virtual invisibility of the Chiang Mai Initiative – Asia's regional reserve pooling arrangements. Korea turned to the US Fed for primary support when push came to shove and the country teetered toward a fully-fledged financial crisis. Even Chian Mai Initiative partners – the Bank of Chinaand the Bank of Japan – played only a secondary role and outside the Chian Mai framework at that. In order for member countries to make greater use of the Chian Mai Initiative in future, more concrete and specific governance structure and implementation details are needed. Formalising and institutionalising swap lines so that they are transformed from temporary anti-crisis measures to more long-term mechanisms for liquidity support may dampen the need for precautionary reserve hoarding.

Finally, since financial instability in emerging markets is usually the result of volatile capital flows and the fundamental purpose of precautionary reserves is to limit financial instability, some emerging markets may opt to dampen the precautionary accumulation of foreign-exchange reserves by controlling volatile capital flows. According to this argument, controlled financial integration, which retains some restrictions on capital flows, may limit financial instability. This, in turn, will limit the need for precautionary foreign-exchange reserves.

One possible solution to sudden stops and de-leveraging may be a Pigovian tax scheme, where inflows of portfolio flows and external borrowing above a threshold may be taxed at an increasing rate, reflecting the resultant higher exposure of the central bank to possible future bailout of the banking system.2 Such a tax scheme, implemented before the inflow of foreign funds takes place, may curtail exposure to the growing hazard facing the recipient country due to possible de leveraging (see Aizenman 2009). It may induce the foreign investor to internalise the externality associated with possible costs of de-leveraging, and would reduce the cost of self insurance.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this paper are personal. No responsibility for them should be attributed to the Asian Development Bank or the NBER.

Footnotes

1 Swap lines resemble unsecured sovereign debt, and may be constrained by similar considerations. Hence, factors that explain better access to the sovereign borrowing may also explain easier access to larger swap lines. These factors include low volatility, higher trade openness, credibility associated with history of low incidence of default and good growth prospects, quality of institutions, etc. All these factors play a role in explaining the differential patterns of access and the use of swap lines.

2 The design of the FDIC deposit insurance scheme in the US may be viewed as generating outcomes similar to such a Pigovian tax scheme. The FDIC charges insurance premiums on bank deposits at a rate that ideally should reflect the riskiness of banks’ investments. The insurance premium is akin to a tax on banks’ borrowing, inducing the bank to internalize the impact of its balance sheet on the possibility of future bailouts. As with any insurance scheme, care should be taken to deal with the possibility of moral hazard.

References

Auer, Raphael and Sébastien Kraenzlin (2009), “Money market tensions and international liquidity provision during the crisis”, VoxEU.org, 14 October.

Aizenman, Joshua (2009), “Alternatives to sizeable hoarding of international reserves: Lessons from the global liquidity crisis”, VoxEU.org, 30 November.

Aizenman Joshua, Jinjarak Yothin, and Donghyun Park (2010), “International reserves and swap lines: substitutes or complements?” NBER Working Paper No. 15804

Aizenman, Joshua and Gurnain Pasricha (forthcoming), “Selective Swap Arrangements and the Global Financial Crisis: Analysis & Interpretation”, International Review of Economics and Finance.

Obstfeld, Maurice; Jay C Shambaugh, and Alan M Taylor (2009), “Financial Instability, Reserves, and Central Bank Swap Lines in the Panic of 2008”, American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings, 99(2):480-86.

Park, Yung-Chul (2009), “Reform of the Global Regulatory System: Perspectives of East Asia's Emerging Economies," ABCDE World Bank Conference. Seoul.