Unemployment rates remain high in most advanced countries. Many scholars have drawn attention to an apparent decoupling of unemployment increases from output declines during the Great Recession (e.g. IMF 2010, Cazes et al. 2011).

Figure 1 shows peak-to-trough declines in output for a group of OECD countries during the Great Recession against the change in unemployment over the same period. The correlation is essentially zero. In the language of economics textbooks, Figure 1 suggests a breakdown of Okun’s Law, the short-run negative relationship between output and unemployment reported by Arthur Okun in 1962.

Figure 1. The Great Recession: Peak-to-trough output and unemployment changes (simple scatter plot)

We believe the casual impression that "Okun’s broken" is misleading (Ball, Leigh and Loungani 2013). Two adjustments are needed to restore Okun’s Law (as shown in Figure 2):

- The first adjustment is to account for differences in the duration of the recessions;

For the set of recessions shown in these charts, the period from peak to trough ranges from two quarters to seven quarters. As we show in our paper, Okun’s Law implies a relationship between the changes in unemployment and output only if we control for this factor.

- The second adjustment accounts for the fact that, historically, the coefficient in Okun’s Law varies across countries.

Figure 2. The Great Recession: Peak-to-trough output and unemployment changes (with adjustments for duration of recessions and country-specific Okun coefficients)

Notes: Σ ΔU and Σ ΔY denote the cumulative peak-to-trough change in the unemployment rate and in the log of real GDP, respectively. T denotes the duration of the recession (peak to trough in quarters). αi and βi denote country-specific Okun coefficients.

With these two adjustments, the actual changes in unemployment – shown on the vertical axis of Figure 2 – line up with the fitted values predicted by Okun’s Law, as shown on the horizontal axis.

Spain’s large rise in unemployment is explained almost entirely by the fact that its Okun coefficient is unusually large, along with the length of its recession. Germany’s level of unemployment is lower than that predicted by Okun’s Law – which may be due to its extensive use of worksharing programs – but the residual is modest compared to the cross-country differences in unemployment changes.

Policy implications

McKinsey (2011) argues that Okun’s Law has broken down and that a return to full employment will require not just “healthy GDP growth [but also] major efforts in education, regulation, and even diplomacy”. A recent column Vox column argued that “we can’t just blame the recession” for the high unemployment during the Great Recession (Dobbs and Madgavkar 2012). Whether or not Okun’s Law holds matters for the interpretation of unemployment movements and for policymakers.

In contrast, our results are consistent with textbook models in which aggregate shocks cause changes in output, which in turn lead firms to hire and fire workers. In these models, when unemployment is high, it can be reduced through demand stimulus. Our results suggest that Okun’s Law is alive and well: when output recovers, the jobs will come back.

Cross-country variation in the Okun coefficient

What is true is that the extent to which the jobs come back will differ across countries. While a stable Okun’s Law fits the data for most countries, the coefficient in the relationship – the effect of a 1% change in output on the unemployment rate – varies across countries.

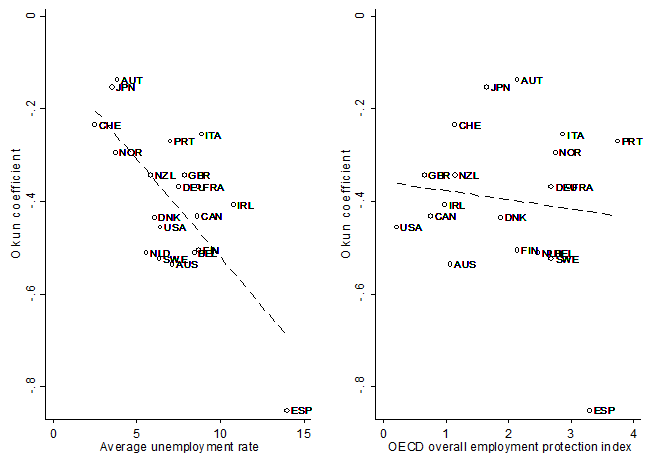

In our paper we report estimates of Okun’s Law for 20 OECD countries using annual data from 1980-2011. The fit is good for most countries except Austria and Italy. The estimated coefficients do vary across countries but most are spread between –0.25 and –0.55. Countries with higher average unemployment rates have higher Okun coefficients in absolute value (see left panel of Figure 3), suggesting there are common factors that drive both variables.

We have had limited success in finding factors that can explain the cross-country pattern of coefficients. A notable failure is the OECD’s well-known index of employment protection legislation. In theory, greater employment protection should dampen the effects of output movements on employment and therefore reduce the Okun coefficient. But, as shown in the right panel of Figure 3, which plots the OECD’s overall employment protection legislation index (averaged over 1985-2008), the relationship has the wrong sign, and it is statistically insignificant. We also find no relationship between the Okun coefficient and the various components of the employment protection legislation index.

Figure 3. Cross-country variation in Okun coefficients (Okun coefficient vs. candidate variables)

Notes: Average unemployment rate denotes 1980-2011 mean. OECD overall employment protection index denotes 1985-2011 mean based on available data.

It appears that the labour markets of many countries have idiosyncratic features that influence the coefficient. These features – not one or two variables that we can measure for all countries – probably account for most of the variation in the coefficients. At one extreme, Spain has an Okun coefficient of –0.85, which is much higher in absolute value than any other country’s. The natural explanation is the unusually high incidence of temporary employment contracts, which makes it easier for firms to adjust employment when output changes, raising the Okun coefficient. At the other extreme, Japan’s small Okun coefficient, –0.16, probably reflects Japan’s tradition of 'lifetime employment', which makes firms reluctant to make workers redundant. A possible explanation for Switzerland’s low coefficient, –0.24, is the frequent use of foreign workers in Switzerland. When employment rises or falls, migrant workers move in and out of the country. Changes in employment are accommodated by changes in the labour force, and unemployment is stable.

Austria’s data are puzzling. Its Okun coefficient, –0.14, is the smallest for our 20 countries, and we have not found an explanation for this result.

Conclusions

Our evidence suggests that jobs and growth remain coupled in most countries. There may be good reasons for the structural reforms that many propose as a way to boost job creation, but undertaking them in the belief that Okun’s Law has broken down should not be one of them.

References

Ball, Laurence, Daniel Leigh and Prakash Loungani (2013), “Okun’s Law: Fit at 50?” NBER Working Paper 18668, also IMF Working Paper 13/10.

Cazes, Sandrine, Sher Verick, and Fares Al-Hussami (2011), “Diverging Trends in Unemployment in the US and Europe: Evidence from Okun’s law and the Global Financial Crisis”, Employment Working Paper No. 106, International Labour Organisation.

Dobbs, Richard and Anu Madgavkar (2012), “Why the jobs problem is not going away”, VoxEU.org, 19 September.

IMF (2010), “Unemployment Dynamics During Recessions and Recoveries: Okun’s Law and Beyond”, World Economic Outlook, Chapter 3, April.

McKinsey Global Institute (2011), “An Economy That Works: Job Creation and America’s Future”.

Okun, Arthur M (1962), “Potential GNP: Its Measurement and Significance”, reprinted as Cowles Foundation Paper 190.