Labour coercion is arguably as old human civilisation. In the words of Acemoglu and Wolitzky (2011), “the majority of labour transactions throughout much of history and a significant fraction of such transactions in many developing countries today are coercive”.

Indeed, labour coercion is at the heart of much of the literature on long run development and institutional change (Domar 1970, Acemoglu et al. 2001, Engerman and Sokoloff 2002, Nunn 2008, Dell 2010, Naidu and Yuchtman 2013, Bobonis and Morrow 2014, Ashraf et al. 2017). Despite this, rigorous empirical evidence on labour coercion is scarce and is mostly focused on relating present-day outcomes to historical labour coercion.

The term ‘labour coercion’ is used quite broadly to describe the use of, or threat of, force in convincing workers to accept labour contracts they otherwise would not.

However, labour coercion can take two quite distinct forms, and this important distinction is often not well articulated. The distinction is best seen by imagining a standard principal-agent framework. In broad terms, a firm (the principal) offers a labour contract to a worker (the agent). If effort is not observable, it can only be inferred from the outcome, which can be ‘good’ or ‘bad’ (e.g. high output or low output). The firm can incentivise its workers to exert effort by offering them a higher wage if the good outcome materialises. The difference in the wages the firm pays in the good and bad state needs to be sufficiently high that workers exert effort (i.e. the ‘incentive compatibility constraint’ binds). The second constraint on the contract is that workers may walk away from it if they can earn a higher expected wage elsewhere. The expected wage (averaging over the effort-dependent outcome probabilities) thus needs to exceed the worker’s outside option (i.e. the ‘participation constraint’ binds).

Coercion of the worker can be quite simply introduced into this setup by allowing firms to pay a ‘negative wage’ if the bad outcome occurs. This is simply the more cost-effective flipside of paying a higher wage if the good outcome occurs. Negative wages describe a world in which workers can be ‘punished’ (i.e. a world with coercion). In this way, slavery, serfdom, or indenture can be nested inside a standard economic framework and, indeed, there is a long tradition in economics that does this (Chwe 1990). However, the participation constraint still binds when there is coercion. Even in the extreme case of slavery, outside options were usually not zero so long as slaves could run away and had a chance of evading capture. The interaction of the two constraints implies that there is complementarity in coercive activities – firms can punish workers more severely if they can also reduce their outside options.

In many modern-day labour markets, it may be entirely impossible for a firm to reduce a worker’s outside options and the complementarity between coercion that punishes workers and coercion that reduces outside options can therefore safely be ignored. However, for countries at the early stages of structural transformation – where workers’ outside options are not to work for a different firm or in a different sector, but to be self-employed in the informal sector as a yeoman farmer or artisan (a state that describes most of modern economic history and many developing countries today)1 – coercion that reduces workers’ outside options was and still is critical.

This was recognised by early development economists, as attested, for example, by Arthur Lewis’ famous quote that “the fact that the wage level in the capitalist sector depends upon earnings in the subsistence sector is of immense political importance, since its effect is that capitalists have a direct interest in holding down the productivity of the subsistence workers. Thus the owners of plantations, if they are influential in government, are often found engaged in turning the peasants off their lands” (Lewis 1954).

Despite its apparent importance, the existence of coercion aimed at reducing workers’ outside options (i.e. coercion that is not aimed directly at workers although its goal is to reduce wages) has escaped rigorous empirical analysis. Our recent paper attempts to fill this gap. We study 14 Caribbean sugar islands over an 80-year period from right after the end of slavery in 1838 (i.e. at the inception of free labour markets) until the outbreak of WWI in 1914 (Dippel et al. 2017). In the trade-off between ‘more data’ and ‘low unit heterogeneity’ (i.e., an apples-to-apples comparison), we are siding firmly on the side of low unit heterogeneity. We compare 14 islands that shared a British colonial history and institutional framework, a monocrop economic structure based on sugar and slavery, and an ethnic/racial composition in which the population consisted of “2–3% [British] whites, mostly landed, 8% coloureds, who had been freed earlier and almost 90% blacks, recently emancipated” (Taylor 1885).

From these shared initial conditions, we investigate the evolution of labour markets, the formal plantation system, and coercive government institutions over the ensuing 80 years. Identification in our data comes from a subtle difference in geography, which ultimately ended up giving rise to large differences in the islands’ long-run economic structure, the coercive power of the state, and institutional quality.

Figure 1 Elevations of St Vincent and Barbados

Figure 1 depicts the elevations of two neighbouring islands, St Vincent on the left and Barbados on the right.2 On the eve of slave emancipation, both islands grew only sugar. Sugar ratoons grow well on flat land and low elevations. Because of this, the whole of Barbados was suitable for sugar, and on the eve of Emancipation over 95% of Barbados’ land was owned by plantations. In St Vincent, sugar was grown on a suitable coastal ‘doughnut’, while its hinterland was unused. On the eve of Emancipation, 70% of its land was ‘un-alienated’ (i.e. public) Crown land. Under slavery, this difference in geography was irrelevant.3 The higher elevation hinterlands were fertile but not suitable for the major plantation crops. On the small islands we study, hinterlands were not remote enough to allow runaway slaves to maroon in. In short, the hinterlands were a non-factor before Emancipation. In 1836, the sugar plantation system in Barbados was therefore much the same as that in St Vincent.

This changed after Emancipation. The freed slaves of St Vincent, Dominica, Jamaica and other islands settled the hinterlands (legally or illegally) and became small-hold farmers that grew crops for local consumption as well as export crops like cocoa and livestock. The freed slaves of Barbados and Antigua had nowhere to go – British colonial laws prevented their migration to other islands, and they were confined to plantation work. They operated in labour markets that were nominally free but in which workers’ outside options consisted of small garden plots which belonged to the large planters and conferred no security of tenure. When peasants in Barbados refused to work on the plantations, the planters would evict them from their garden plots. When they refused to leave, the local constables would arrest them for squatting. By contrast, St Vincent’s government institutions (e.g. its police and judges), were far less able to coerce peasants into plantation work.

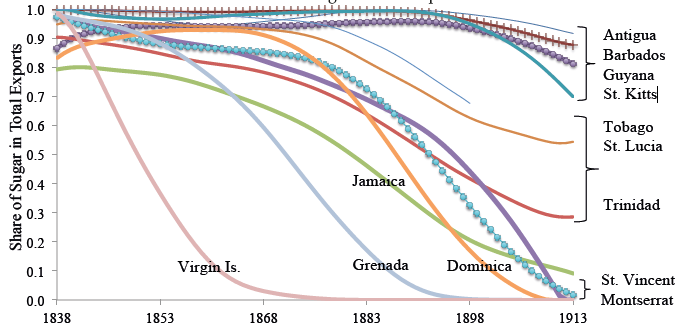

As a result, there was a stark divergence in the power of the plantations over the small-hold farmers in the different islands, as shown in Figure 2. In 1838, plantation sugar was king in all the islands. By 1913, the plantation system had completely collapsed in about half of the islands, and had been dramatically reduced in a few more, yet was also thriving on certain other islands.

Figure 2 Sugar exports from Caribbean islands, 1838-1913

Our main focus is on showing the effect of this differential evolution of the plantation system on labour markets and coercive policies. We find that the collapse of the plantation system significantly raised agricultural wages: a 50% reduction in the economic power of the plantations raised wages by 60%. This is made more surprising by the fact that the plantation system was the main wage-paying sector in the islands, as we document. In other words, wages rose at the same time as labour demand fell!

We rationalise this in a simple model of wage setting where wage-paying firms can lobby the government to enact/enforce coercive (i.e. wage-reducing) policies. Consistent with the simple model and our overall narrative, we show that coercion aimed at smallholders – specifically trespassing-related and squatting-related court cases, as well as rates of imprisonment – significantly fell when the plantation system declined.

Interestingly, we are able to show that about three-quarters of the plantation system’s effect on wages can be explained by its effect on coercion. In other words, this research shows not only that the plantation system was associated with coercion but also that the plantation system reduced wages because it increased coercive policies.

References

Acemoglu, D and A Wolitzky (2011), “The economics of labor coercion”, Econometrica 79(2): 555–600.

Acemoglu, D, S Johnson and J A Robinson (2001), “The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation”, American Economic Review.

Ashraf, Q H, F Cinnirella, O Galor, B Gershman and E Hornung (2017), “Capital-skill complementarity and the emergence of labor emancipation”, Technical Report.

Bobonis, G J and P M Morrow (2014), “Labor coercion and the accumulation of human capital”, Journal of Development Economics 108(0): 32–53.

Chwe, M S-Y (1990), “Why were workers whipped? Pain in a principal-agent model”, The Economic Journal 100(403): 1109–1121.

Dell, M (2010), “The persistent effects of Peru’s mining mita”, Econometrica 78(6): 1863–1903.

Dippel, C, A Greif and D Trefler (2017), “Outside options, coercion, and wages: Removing the sugar coating”, working paper.

Domar, E D (1970), “The causes of slavery or serfdom: A hypothesis”, Journal of Economic History 30(1): 18–32.

Engerman, S L and K L Sokoloff (1997), “Factor endowments, institutions, and differential paths of growth among new world economies: A view from economic historians of the United States”, in S Harber (ed), How Latin America Fell Behind, Stanford: Stanford University Press: 260–304.

Lewis, W A (1954), “Economic development with unlimited supplies of labour”, The Manchester School 22(2): 139–191.

Naidu, S and N Yuchtman (2013), “Coercive contract enforcement: Law and the labor market in nineteenth century industrial Britain”, American Economic Review 103(1): 107–44.

Nunn, N (2008), “The long term effects of Africa’s slave trades”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 123(1): 139–176.

Taylor, S H (1885), Autobiography, 1800-1875, Longmans, Green.

White, R (2017), “The republic for which It stands: The United States during reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865-1896”, Oxford History of the United States.

Endnotes

[1] Even in the US, wage labour did not become the common form of work until as recently as the 1890s (White 2017: Chapter 1).

[2] The islands are correctly scaled and oriented relative to each other, but the distance between them is reduced by 90%.

[3] There were returns to scale in sugar growing at the level of the plantation but not at the level of the island.