Education and political institutions are likely to be highly interconnected. Several studies support the hypothesis that education is a strong predictor of democracy and quality of institutions (e.g. Barro 1999 and Glaeser et al. 2007). Another strand of the literature discusses how political regimes influence the educational system of a country. Bowles and Gintis (1976) argue that norms and values within schools tend to reproduce the internal organisation of societies and their labour market structure.

Governments can potentially shape the ideology of students by directly influencing the contents of their studies, and by determining the identity of the future elites through establishing the criteria used to evaluate students and select those admitted to advanced studies. If they are successful in doing this, one would expect the returns to education (and more generally the effect of schooling on labour market outcomes) to depend on the political institutions of a country. How do individuals with schooling backgrounds from countries with different political institutions then fare in a common labour market? Specifically, do individuals who received schooling under a socialist regime in Eastern Europe fare worse nowadays in the free labour market than individuals who received schooling in a democratic society?

Background

This question is generally hard to answer, given that many things other than schooling differ between two individuals from different countries. We answer this question by relying on the reorganisation of the school system in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) towards West German standards during the transition from a socialist to a democratic regime immediately after reunification. The East German school system differed from the West German one in terms of curricula, teaching style, and access criteria to higher education.

The East German curriculum systematically aimed at creating a socialist personality – this goal found its way into every single school subject. Moreover, almost 14% of the overall teaching hours for grades 7 to 10 was devoted to teaching specifically socialist subjects, and the main foreign language taught in schools was Russian. Yet, in the main subjects German, maths, and natural sciences, East Germans were taught at least as many hours as West Germans.

Besides the curricula, there existed important differences between the East and West when it comes to teaching styles. In GDR schools, critical thinking was not incentivised, and divergent opinions were suppressed. Theorems and theories were never the subject of discussion, but rather dogmas to be memorised. The national curricula were extremely specific in what needed to be covered in each week, in part imposing detailed structures of how to cover certain topics, leaving minimal scope for teacher or student initiatives.

Last, access to higher education was influenced by the political system. Besides academic credentials, political criteria – such as the political and social involvement of the student, her/his identification with the GDR, and the intention of a military career – determined whether a student was allowed to attend high school or university. On the other hand, each student in the GDR had the right (as well as the obligation) to do an apprenticeship, and firms were obliged to offer apprentices a permanent position at the end of their vocational training.

This educational system in the GDR was transformed very rapidly after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Any elements in the curricula directed towards the creation of a socialist personality were deleted, and restrictions in access to high school and college not based on academic merit were quickly eliminated, as were restrictions in the choice of apprenticeship. The teaching style changed to allow for critical discussion and student and teacher initiative. Because many firms suffered from the economic transition, however, during the transition many apprenticeship contracts were resolved, especially for people not very advanced in their apprenticeship.

How to assess the effect of socialist education

We study the impact of an additional year of socialist education on the likelihood of obtaining a college degree and on several labour market outcomes, such as employment, working hours, wages, and type of profession. As our main data source we use the German Micro census, a repeated cross-sectional annual survey on a 1% random sample of the German population.

We focus on East German individuals who were still in school when the Berlin Wall fell in November 1989. Our identification strategy relies on the consideration that within the same birth cohort, individuals in the GDR born earlier in the year started school at a younger age and had received one more year of socialist education at reunification. In the GDR, children turning six on or before 31 May of a given year were per decree enrolled in the first grade by 1 September of the same year. We consider individuals born on or after the first of June as treated, individuals born on 31 May or before are instead part of our control group. Because of data availability, we focus on cohorts 1971-1977. Within the same birth cohort, treated individuals in East Germany belonging to cohorts 1971 to 1977 were exposed to one year less of the socialist schooling system.1

We further split the sample into two separate cohort groups: the first born 197-73; and the second 1974 to 1977. When the Berlin Wall fell, individuals in the cohort group 1974-77 were still in the 10th grade or below. For any given cohort in this group, treatment means having received one year less of GDR education than the control group, and thus the length of exposure to socialist contents of education and teaching style is the relevant difference between treatment and control in the cohort group 1974 to 1977. Our hypothesis is that the longer the exposure to socialist education, the stronger was the transmission of values that may not be useful in the unified German labour market and, more generally, in Western societies. For the cohort group 1971 to 1973, the treatment and control groups differ in how far they have been affected by access restrictions to higher education.

Results

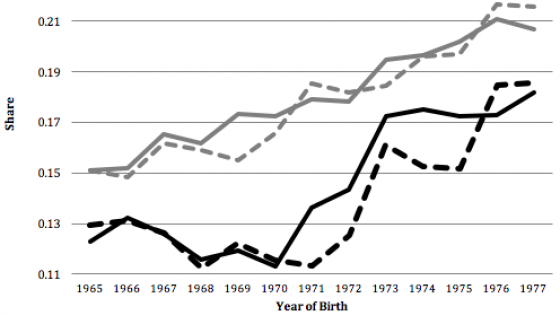

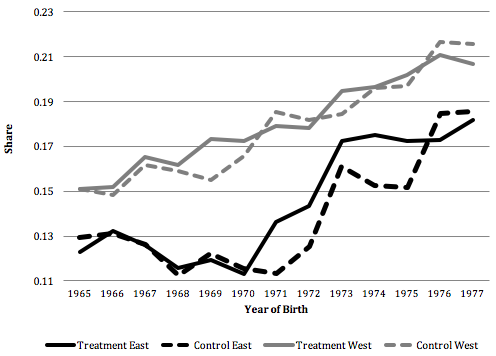

We find significant negative effects of the length of exposure to a socialist education on college completion rates. Figure 1 shows the college completion rate by birth cohort for four different groups, separated by residing in the East (thick line) and West (thin line), and by being in the treated group (solid line) or in the control group (dashed line). In the West, individuals in the treatment group, and thus having been enrolled in school at a later age, exhibit slightly higher college completion rates than individuals in the control group for most birth cohorts. In the East, we observe the same pattern. Yet, starting with birth cohort 1971 (which is the oldest cohort that may have been affected by the reorganisation of the school and apprenticeship system in East Germany after reunification) the differences become quite large. Within the same birth cohort, individuals exposed to one year less of socialist schooling are around 1% more likely to complete college education.

Figure 1 Respondents with a college degree

We also analyse long-term labour market outcomes once individuals from these birth cohorts are 31-35 years old. For the younger birth cohort group, for whom exposure to socialist teaching varies between treatment and control, we find long-run effects of socialist schooling on both employment rates and hours worked conditional on employment. Treated individuals, who were exposed to socialist schooling for one less school year, exhibit 2% higher employment rates and 1.5% higher hours worked. For the older birth cohorts, less exposure to non-meritocratic access restrictions in the treated group leads to 4% higher wages and a 5% higher probability of having a professional job. At the same time, being treated in the East is associated with a 2% lower likelihood of being employed. The elimination of non-meritocratic restrictions in access to college and apprenticeship choice apparently allowed students to acquire the human capital they needed to achieve a better occupational status in the labour market. The contrasting result on employment might come from an increasing variance in labour market success after reunification. Individuals who potentially struggle in the labour market might have been better taken care of in the regulated GDR system than in the free labour market of the West. Therefore, the overall effect of being treated for this cohort group leads to a larger spread in labour market outcomes – there are more individuals not being employed, but conditional on being employed treatment leads to higher wages and a higher probability of achieving a professional status in the East than in the West.

While the effect of a socialist education on college attainment is present for men and women, the long-term labour market effects are only present for men. For women, the negative effects of a socialist education seem to disappear in the long run. This could be because women encounter more career breaks, washing out the effects of the socialist education, or because the socialist education, which stressed the importance of female participation in the labour market, had the additional effect on women that it increased their long-run labour force attachment.

Implications

We present evidence that authoritarian, and in particular socialist, forms of government might have a long-term impact on several important labour market outcomes by (i) adopting non-meritocratic criteria to select students and grant access to higher education; and (ii) shaping the contents of curricula to indoctrinate pupils and preserve consensus towards the regime in power, with a teaching style that does not encourage critical discussion. Thus, our work contributes to the large body of literature that shows that schooling matters through many different channels.

One caveat of our analysis is that it is carried out against the background of a depressed labour market in East Germany right after reunification. The high unemployment rates might have made it more difficult for young people to switch education and adjust their occupational choice after the fall of the Berlin Wall, and therefore the effects of restricted occupational choice and non-meritocratic restrictions in access to college might have been larger than in settings with a booming labour market.

References

Barro, R J (1999), "Determinants of Democracy", Journal of Political Economy, 107 (S6): S158-S183

Bowles, S, and H Gintis (1976), Schooling in Capitalist America: Educational Reform and the Contradictions of Economic Life, New York, Basic Books

Fuchs-Schündeln, N, and P Masella (2016), "Long-Lasting Effects of Socialist Education", Review of Economics and Statistics, forthcoming

Glaeser, E L, G Ponzetto, and A Shleifer (2007), "Why Does Democracy Need Education?", Journal of Economic Growth, 12 (2): 77-99

Endnotes

[1] Since the educational system in West Germany did not experience any major changes in the 80s and early 90s, treated respondents born between 1971 and 1977 and educated in the West instead received the same type of education as non-treated respondents. By analysing the difference of treatment effects between East and West we are able to control for any effects that might arise simply due to entering school at a slightly older age.