In the last decade, the number of US children diagnosed with asthma and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has inexplicably been on the rise. ADHD is a neurological condition defined by persistent symptoms of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity. It is one of the most common mental health disorders affecting school-aged children. Asthma is a chronic inflammation of the airways in the lungs. It is one of the most common physical chronic childhood illnesses, and the most frequent cause of childhood emergency room (ER) visits and hospitalisations. The number of children whose parents reported that they had ever been diagnosed with ADHD increased by two million between the 2003 and 2011 waves of the National Survey of Children’s Health, rising to 11% of all school-aged children (Visser et al. 2014). Between 2001 and 2010, the number of children who had been diagnosed with asthma increased from 8.7 to 9.3%, although the number who reported an asthma attack in the past month held steady and the number of asthma-related hospitalisations and deaths continued to fall (CDC 2012).

While the increase in asthma has been described as a “mystery” (CDC 2011), researchers have found that the increase in ADHD caseloads can, in part, be explained by school accountability pressures and special education financing incentives. For example, Bokhari and Schneider (2011) look at the effect of the school accountability laws on medical diagnoses and subsequent treatment options of school-aged children. They use variation across states and over time in specific provisions of the accountability laws and find that accountability pressures matter. Children in states with more stringent accountability laws are more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD and consequently prescribed psychostimulant drugs for controlling the symptoms. Morrill (2017) looks at the differences in special education financing policies across states and finds that children living in states where schools receive more funding for educating students with disabilities are 15% more likely to report having ADHD and 22% more likely to be taking medication for ADHD.

While school-level incentives clearly matter, ADHD diagnoses have been rising even in states, like South Carolina, without any changes in such incentives, and rates of other chronic conditions such as asthma are also rising. Increasing rates of chronic conditions among children are a grave concern, and also a puzzle given that other health indicators such as mortality have shown great improvement, and underlying causes, such as smoking and pollution, have been declining (Currie and Schwandt 2016).

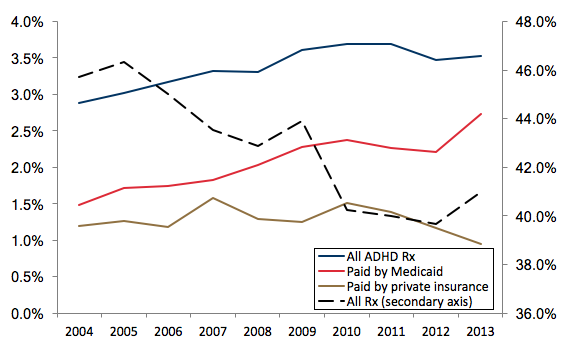

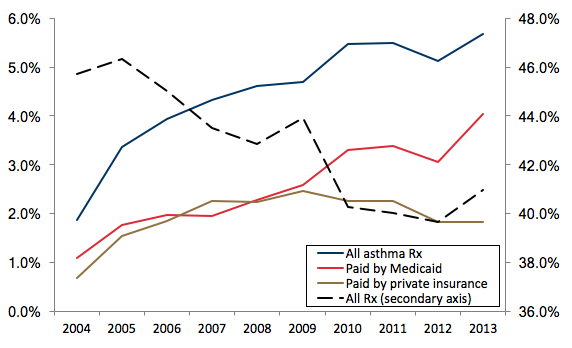

In a new paper, we propose a novel hypothesis, which is that the increase in diagnoses for both ADHD and asthma was driven at least partially by changes in Medicaid, the means-tested public health insurance programme that covers low- to moderate-income children (Chorniy et al. 2017). In national data, the increase in treatment for ADHD and asthma over the course of the 2000s was largely accounted for by children on Medicaid, and not by children with private health insurance coverage. Figure 1 shows that while the overall number of children taking any kind of prescription drug fell, the fraction with prescriptions for ADHD medications rose, and all of the increase is accounted for by children on Medicaid. Figure 2 shows that the fraction of children taking prescription drugs for asthma has also increased. Up to 2009, it increased at a similar rate for the privately and publicly insured, while after 2009 all of the increase has been among Medicaid recipients.

One of the largest changes in Medicaid over the course of the 2000s is that it was converted from a largely ‘fee-for-service’ programme, in which physicians were reimbursed for each service provided, to a managed care model in which providers received a capitated fee intended to cover all services provided to a covered child. Nearly 80% of states had transitioned their Medicaid programmes to managed care by 2016.

Figure 1 Nationwide trends in filled ADHD prescriptions

Note: The sample includes all ADHD prescriptions filled by children under 17 years old.

Data source: Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (MEPS), 2004-2013.

Using Medicaid claims from South Carolina, we show that the shift to managed care contributed to the increase in asthma and ADHD caseloads through three mechanisms (Chorniy et al. 2017). First, managed care improved access to most forms of care (though the use of specialists fell). Second, capitated payments to managed plans are ‘risk adjusted’ so that insurance plans receive higher payments for patients who are thought likely to generate higher expenses. In South Carolina, plans receive higher payments if children fill a prescription for one of the listed chronic conditions, which includes asthma and ADHD. Hence, the risk-adjustment mechanism creates an incentive to write at least one prescription for a condition with an added weight, although there is little direct incentive to ensure follow through on medication compliance. Third, managed care plans are evaluated on how well they deliver recommended screenings for children, and other things being equal, would be expected to yield more cases.

These features of managed care plans may be particularly likely to generate increases in ADHD and asthma caseloads. Both conditions are common, so that additional screenings would be likely to turn up more cases. They are also difficult to definitively diagnose, but are nevertheless likely to be diagnosed and treated by family physicians rather than specialists. And for both asthma and ADHD, the frontline treatments are medication. Thus, diagnosing either ADHD or asthma will increase a plan’s capitated payment without necessarily increasing the cost of caring for a child significantly.

Figure 2 Nationwide trends in filled asthma prescriptions

Note: The sample includes all asthma prescriptions filled by children under 17 years old.

Data source: Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (MEPS), 2004-2013.

The estimates suggest that all of these forces are at work. The switch to managed care in South Carolina increased the probability that a child on Medicaid received a well-child visit by 49.0%, and there were increases in the probability of having blood work, developmental and hearing screens, and vaccinations. There was also a 58% increase in the child’s individual risk-adjustment weight, with a third of the increase being accounted for by increased prescribing for asthma and ADHD alone.

The actual increase in ADHD and asthma caseloads in the Medicaid population over the sample period was 30.4% and 36.4%, respectively. The switch to managed care increased caseloads for these two conditions by 26.6% (ADHD) and 29.9% (asthma). An upper bound on the effect of increased screening alone is 15.7% (ADHD) and 18.2% (asthma). Hence, the switch to managed care accounts for the majority of the increase in diagnoses of these two conditions in this population over this period, and an increase in screening alone cannot account for all of the increase.

In principle, increases in diagnoses and treatment should improve health outcomes. Unfortunately, there is little evidence that this is the case. Instead, there were increases in preventable hospitalisations and in almost all types of ER visits. A large part of the increase in ER visits was driven by asthma, and over 40% of children with asthma received fewer than two prescriptions for asthma in the past 12 months, a proportion that remained constant with the advent of managed care. The only category of care that showed a decrease was office visits to specialists.

While managed care plans improved access to primary care physicians and helped to ensure that a larger share of children on Medicaid benefitted from preventive care, other features of the programme apparently backfired. First, risk-adjustment incentives distorted prescribing practices in that more children received at least one prescription medication, but providers had no incentive to follow-up on adherence.

Second, access to primary care and specialists seems to have changed in a way that encouraged reliance on emergency rooms even for non-urgent care. The large and striking changes in patterns of utilisation may or may not reflect deterioration in underlying child health, but they are certainly not consistent with improvements in the efficiency of the care provided under the Medicaid programme. They suggest that patients in Medicaid managed care may have experienced difficulties accessing primary care outside of the annual well-child visit that managed care plans are mandated to provide.

Children on Medicaid are among the most vulnerable patient populations. The evidence indicates that their care is very sensitive to the incentives provided by the reimbursement system facing insurers. Moreover, because Medicaid covers approximately 40% of US children, trends in diagnoses in this population are potentially large enough to help explain the mystery of climbing national rates of common childhood chronic conditions at a time when other child health indicators are improving.

References

Bokhari, F A and H Schneider (2011), “School accountability laws and the consumption of psychostimulants”, Journal of Health Economics 30(2): 355–372.

CDC (2011), “Asthma in the US Vital Signs”, Centers for Disease Control, May.

CDC (2012), “National Surveillance of Asthma: United States, 2001–2010, Series3 #35”, Centers for Disease Control, Hyattsville MD: National Center for Health Statistics, November.

Chorniy, A, J Currie and L Sonchak (2017), “Exploding asthma and ADHD caseloads: The role of Medicaid Managed Care”, NBER, Working Paper No 23983.

Currie, J and H Schwandt (2016), “Mortality inequality: The good news from a county-level approach”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 30(2): 29-52.

Morrill, M S (2017), “Special education financing and ADHD medications: A bitter pill to swallow”, North Carolina State University, Working Paper, April.

Visser, S N, M L Danielson, R H Bitsko, J R Holbrook, M D Kogan, R M Ghandour, R Perou and S J Blumberg (2014), “Trends in the parent-report of health care provider-diagnosed and medicated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: United states, 2003–2011”, Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 53(1): 34–46.