If one is searching for a measure of how widely recognised the current shortcomings of the Eurozone are, one should look no further than Brussels’ plan for a genuine Economic and Monetary Union (Begg 2015). Agreement on the need for a solution co-exists with apparently stark disagreement on the causes. One view is that ‘design flaws’ (De Grauwe 2006) deepened imbalances, while another is that ‘policy mistakes’ (Sandbu 2015) hindered convergence. Both views, however, rely upon ‘asymmetries’.

One proposed solution is a flexible euro (Stiglitz 2016) – a two-tier model of a Northern and a Southern euro, where the latter is ‘softer’. One tautological way to explain such a proposal is that the Southern euro would not be part of the ‘core’, or that it would be ‘less core’. However, there remains a dearth of metrics that can help determine threshold levels of ‘coreness’ and support analysis of how it has changed over time. This column presents new research that tries to fill this gap.

The seminal paper here is Bayoumi and Eichengreen (1993). They establish the existence of a core-periphery pattern in the run-up to the European Monetary Union. Using pre-Eurozone data to estimate the degree of business cycle synchronisation, the authors convincingly argue that there is a core (Germany, France, Belgium, Netherlands, and Denmark) where supply shocks are highly correlated, and a periphery (Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and the UK) where synchronisation is significantly lower. They correctly reason, in addition, that this pattern would undermine the Eurozone project if persistent.

This column revisits Bayoumi and Eichengreen (1993) in order to evaluate the effect of the Eurozone on the core-periphery pattern they find using 1963-1988 data. We use the same estimation methodology, sample, and time window (25 years) to replicate their results for 1989-2015. We ask whether the Eurozone strengthened or weakened the core-periphery pattern. We introduce an over-identifying restriction test that produces a new ‘coreness index’ which helps classify countries into core and periphery. Our results suggest that the introduction of the euro weakened the original core-periphery pattern.

Towards a simple theory-driven metric of core-periphery

Bayoumi and Eichengreen’s (1993) methodology develops Blanchard and Quah’s (1989) procedure for decomposing permanent and temporary shocks. Based on the standard aggregate demand-aggregate supply (AD-AS) model, supply shocks have permanent effects on output while demand shocks only have temporary effects. Both have permanent (but opposite) effects on prices.

Using the standard relation between the residuals and demand and supply shocks, exact identification requires four restrictions. Two are normalisations, which define the variance of the shocks, the third restriction is from assuming that demand and supply shocks are orthogonal to each other, and the fourth that demand shocks have only temporary effects on output.

Bayoumi and Eichengreen (1993) did not impose any further restrictions, leaving their model exactly identified. We extend their framework by imposing an additional, fifth, over-identifying, restriction as we explicitly test for a permanent effect of supply shocks on output. In order to test for this over-identifying restriction, we re-estimate Bayoumi and Eichengreen’s (1993) SVAR model but, differently from them, bootstrap the original VAR residuals in a iid1 fashion and generate 10,000 datasets (Campos and Macchiarelli 2016a). For each of these samples, we test for the over-identifying restriction using a LR-test. The percentage of rejections is our coreness index. The lower (higher) the percentage of rejections, the more a country is said to be part of the centre (periphery).

Endogenous optimum currency areas

We see our results as an empirical test of the endogenous OCA hypothesis.2 Figure 1 shows our main results. The residuals (median bootstrapped) are retrieved from a Structural VAR with two lags for all countries, no constant, and using yearly data with respect to Germany, thus closely following Bayoumi and Eichengreen (1993). The over-identifying restriction is imposed and the sample is 1989–2015. As dispersion has decreased compared to the pre-Eurozone era, we argue the results suggest the core-periphery pattern has weakened after 1989.

Figure 1. Correlation of supply and demand disturbances imposing the over-identifying restriction (bootstrapped residuals – median values)

Note: This figure reports median bootstrapped residuals based on 10,000 VAR replications. Structural residuals are retrieved from a SVAR where the over-identifying restriction above is imposed for all countries. The sample for this SVAR is 1989–2015, with two lags for all countries and no constant, as in Bayoumi and Eichengreen (1993).

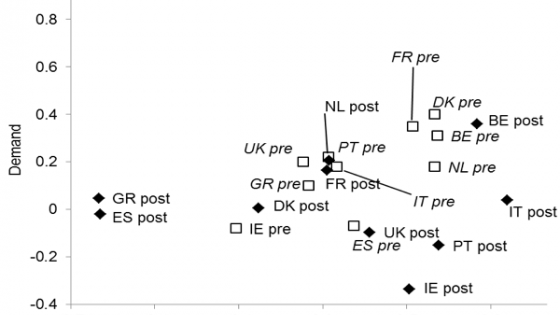

Based on the bootstrapped VAR, we test for the over-identifying restriction described above where (non-)rejection supports classifying the country as periphery (centre). The four countries for which we find a stronger rejection of the over-identifying restriction are Ireland, Spain, Greece, and Portugal.3 Without imposing this over-identifying restriction for these four countries, the core-periphery pattern in Bayoumi and Eichengreen’s terms actually weakens. When the over-identifying restriction is not imposed, Ireland and Portugal move down the demand-axis and Greece and Spain jump to the left (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Correlation of supply and demand disturbances pre and post euro introduction

Note: The figure compares estimates from pre-Maastricht based on Bayoumi and Eichengreen (1993), covering the period 1963-1988, with our equivalent estimates for the period 1989-2015 (‘post’). For each country, we estimate a bi-variate SVAR using (log) real GDP and the (log) deflator, both in first differences. The structural identification of the shocks relaxes the over-identifying restriction for Ireland, Spain, Greece, and Portugal.

Overall, our results support a re-interpretation of the core-periphery pattern – after the Eurozone a new, smaller periphery emerges (Spain, Portugal, Ireland, and Greece) and its dynamics are systematically different from the rest in that, for these countries, the over-identifying restriction is rejected by the data in most cases.4 In Campos and Macchiarelli (2016b) we present a dynamic version of the coreness index that supports these conclusions.

Concluding remarks

Whenever and in whichever form Brexit occurs, for practical purposes the Eurozone will become the EU. Bayoumi and Eichengreen (1993) is a seminal paper because, inter alia, it was one of the first to point out the risks of an entrenched core-periphery to the then nascent Eurozone. Their influential diagnostics were based on data covering 25 years from 1963 to 1988. Using the same methodology, sample, and time window, we replicate their results for 1989-2015. We ask whether the Eurozone strengthened or weakened the core-periphery pattern. Using a new coreness index, our results suggest the Eurozone has significantly weakened the original pattern, in that we find, based on demand and supply shocks, significant changes in the clustering of the set of countries they use. This finding provides renewed support for the endogenous OCA hypothesis. Moreover, one main policy implication is that our results hint there might be less wrong with the euro than commonly thought. In other words, our results suggest that the benefits of keeping the Eurozone together still seem to exceed the costs of breaking it up.

References

Alesina, A and R Barro (2002), “Currency unions”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(2): 409-436.

Bayoumi, T and B Eichengreen (1993), “Shocking aspects of European monetary integration,” in F Torres and F Giavazzi (eds), Adjustment and Growth in the European Monetary Union, Cambridge University Press.

Begg, I (2014), “Genuine economic and monetary union” in S Durlauf and L Blume (eds), The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, Palgrave Macmillan.

Blanchard, O and D Quah (1989), “The dynamic effects of aggregate demand and aggregate supply disturbances,” American Economic Review, 79: 655–673.

Campos, N and C Macchiarelli (2016a), “Core and periphery in the European Monetary Union: Bayoumi and Eichengreen 25 years later,” LSE LEQS Paper No. 116/2016, (forthcoming in Economics Letters).

Campos, N and C Macchiarelli (2016b), “Core-periphery in the European Monetary Union: A new simple theory-driven metrics,” mimeo.

Chari V V, A Dovis and P Kehoe (2016), “Rethinking optimal currency areas”, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Research Department Staff Report 481.

De Grauwe, P (2006), “What have we learnt about monetary integration since the Maastricht Treaty?” Journal of Common Market Studies, 44(4): 711-730.

Farhi, E & I Werning (2015), “Labor mobility in currency unions,” MIT mimeo.

Frankel, J & A Rose (1998), “The endogeneity of the optimum currency area criteria”, Economic Journal, 108(449): 1009-1025.

Glick, R & A Rose (2016), “Currency unions and trade: A post-Eurozone mea culpa”, mimeo.

Hamilton, J (2003), “What is an oil shock?”, Journal of Econometrics, 113: 363-398.

Sandbu, M (2015), Europe's orphan: The future of the euro and the politics of debt, Princeton University Press.

Stiglitz, J (2016), The euro: How a common currency threatens the future of Europe, WW Norton & Company.

Endnote

[1] Independent and identically distributed

[2] See Frankel and Rose (1998) on the endogeneous currency unions hypothesis. The main research question driving the scholarship on optimal currency areas (OCA) regards the costs and benefits of sharing a currency (Alesina and Barro 2002). The main cost is the loss of monetary policy autonomy, while the main benefits are transaction costs and exchange rate uncertainty reductions, which may increase trade and competition. Recent work (a) argues that credibility shocks should be considered as criteria (Chari et al 2016), and (b) OCA criteria should not be thought of as independent (e.g., Farhi and Werning 2015 focus on the interaction between openness and mobility). Some important recent econometric issues are discussed by Glick and Rose (2016).

[3] See Campos and Macchiarelli (2016a) Appendix Table 2A.

[4] One may be concerned that the increase in correlation in supply disturbances may be due to a larger role for oil price shocks in the sample. Following Hamilton (2003) we construct a Net Oil Price Index; we use the Brent Europe crude oil price index at a monthly frequency to evaluate the sensitivity of our results. We find little evidence that this is relevant in our framework and that the responses of real GDP and inflation to demand and supply innovations are driven by net oil price increases while results also remain broadly unchanged if we use the change in the price of oil as an exogenous variable instead. See Campos and Macchiarelli (2016a) for more full details.