In a thought-provoking speech, Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen recently expressed her discontent with macroeconomic research, and the guidance it provides in addressing today’s key policy challenges (Yellen 2016):

“…the events of the past few years have revealed limits in economists' understanding of the economy and suggest several important questions I hope the profession will try to answer.”

“…individual differences within broad groups of actors in the economy can influence aggregate economic outcomes – in particular, what effect does such heterogeneity have on aggregate demand?”

“Are there circumstances in which changes in aggregate demand can have an appreciable, persistent effect on aggregate supply?”

“What determines inflation?… Although inflation fell during the recession, the decline was quite modest given how high unemployment rose”

Indeed, the standard New Keynesian paradigm, which forms the basis of policy analysis in almost all central banks and treasuries, does not provide compelling answers to these questions. First, the standard New Keynesian model assumes a representative household that can perfectly insure against individual income risk. This precludes heterogeneity between households from affecting aggregate demand. Second, the New Keynesian model has been designed to think about how policy can stabilise temporary macroeconomic fluctuations around a given long-run ‘steady-state’ equilibrium, rather than how policy might help to move the economy towards a more desirable long-run outcome. Third, the lack of deflation in the last few years has been rather puzzling from the perspective of the New Keynesian model, which typically predicts deflation once the monetary policy rate becomes constrained by the zero lower bound (e.g. Benhabib et al. 2002, Mertens and Ravn 2014).

Introducing HANK and SAM

Recently, a new generation of models that addresses these shortcomings has emerged and is starting to deliver novel insights. While retaining nominal rigidities, as in the New Keynesian model, the new models replace the representative agent by heterogeneous households that face uninsurable earnings risk, giving rise to inequality in income, wealth, and consumption. These models have been dubbed heterogeneous agents New Keynesian (HANK) models by Kaplan et al. (2016).

A common and important source of earnings risk faced by households is unemployment. It is difficult for households to insure perfectly against job loss, and unemployment spells for that reason often bring about significant income losses and more so in recessions where unemployment duration is also high (such as the aftermath of the financial crisis). The risk of job loss tends to increase at the onset of recessions and the chances of finding a new job for the unemployed are typically considerably lower in recessions than in booms. By implication, the unemployment-related idiosyncratic risk faced by households is countercyclical, but may be affected by stabilisation policy. To take this into account, the new generation of models introduce search and matching (SAM) frictions into the labour market (e.g. Ravn and Sterk 2012, 2016, Challe et al. 2016).

Unstable aggregate demand

The interactions between HANK and SAM have important implications for aggregate demand. A deterioration of labour market conditions makes households’ job prospects more uncertain and introduces a precautionary savings motive. Therefore, desired savings rise, depressing the aggregate demand for goods. In the New Keynesian setting with uninsurable risk, the inflexibility of prices means that firms react to lower goods demand by cutting back on employment, which further stimulate savings desires because labour market outcomes become even gloomier. By contrast, in the standard representative agent New Keynesian model, since unemployment is expected to recover in the future, high current unemployment motivates lower desired savings rate in order to smooth consumption over time. Lower desired savings, in turn, stimulates aggregate demand and stabilises the negative consequences of high unemployment.

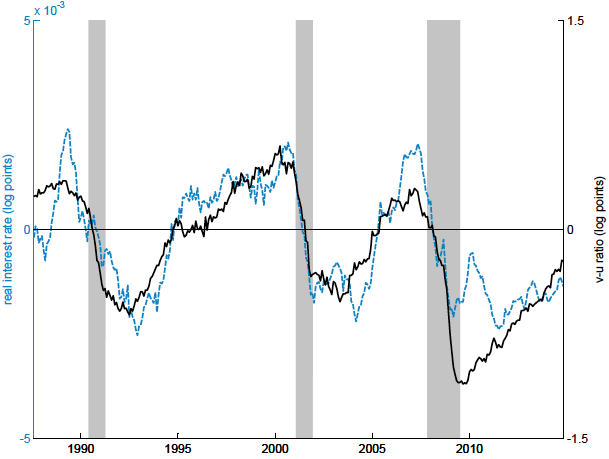

One way of gauging the new and old models is from the relationship between real interest rates and labour market tightness, the ratio of job vacancies to unemployment. Tightness is low in recessions and in the representative agent New Keynesian model, households have an incentive to borrow in bad times for intertemporal reasons. This implies that real interest rates should move in the opposite direction of tightness in the traditional models. Instead, in the new models, the precautionary motive gives employed households an incentive to save in bad times inducing a positive relationship between tightness and real rates. Figure 1 illustrates the time series of tightness and real interest rates for the US and provides strong support for the new models.

Figure 1. Short-term real interest rate (Federal Funds Rate minus six-month moving average of core CPI inflation) and labour market tightness (vacancy-unemployment ratio) in the US

Note: Shaded areas denote NBER recessions.New role for stabilisation policy

A celebrated feature of the New Keynesian paradigm is the Taylor Principle, which says that monetary policy interventions can eliminate self-fulfilling expectations-driven fluctuations in the vicinity of the ‘targeted’ outcome by varying the short-term nominal interest rates by more than one-to-one in response to changes in inflation. Intuitively, the central bank can nip pessimistic expectations about the future economic conditions in the bud by committing to lower the interest rate, were such a scenario to be realised. In the new generation of models, however, the Taylor Principle is no longer sufficient to preclude such equilibria. Intuitively, the feedback loop described above amplifies any initial change in expectations, requiring a more aggressive interest rate cut to prevent pessimistic expectations from becoming self-fulfilling. Furthermore, due to the adverse interaction between unemployment, precautionary saving, and aggregate demand, small aggregate shocks may produce large changes in aggregate output in the new generation of model. Stabilisation policy can intervene in this, for example by addressing the increased savings motive by aiming for lower real interest rates.

Demand-driven long-run stagnation

The new models also have important predictions for long-run outcomes. Following Summers (2014), much discussion has highlighted that economies may have entered a secular stagnation type equilibrium in the aftermath of the Great Recession. Initially proposed by Hansen (1938), secular stagnation refers to extended periods of low growth induced by high savings and low investment. Such outcomes can be rationalised in the new generation of NK models, as it may feature a long-run ‘unemployment trap’, a steady state in which, due to low demand, firms cut investments in job creation to a minimum, creating high unemployment risk, and hence perpetuating low demand. Again, however, such an outcome might be prevented by sufficiently aggressive stabilisation policies.

Understanding missing deflation

The new models also help to explain the recent behaviour of inflation and nominal interest rates. The standard explanation for why central bank policy rates became stuck at (near)-zero levels is that households, for one reason or another, increased their desired savings. This drove down aggregate income and inflation, triggering central banks to cut the policy rate, which eventually became stuck at its lower floor. The standard New Keynesian model predicts a substantial amount of deflation in such a scenario, as the representative agents’ desire to borrow during a recession increases the real interest rate. When the nominal interest rate is stuck at zero, the inflation rate is simply the negative of the real interest rate. Given that the real interest rate is not only positive, but even higher than its long-run level, episodes of zero interest rates must be deflationary in the standard model. Figure 2 illustrates the path of core CPI inflation in the Eurozone, the UK, and the US. The prediction of substantial deflation is obviously not consistent with the data. The new paradigm, by contrast, can rationalise the data, since higher unemployment spurs precautionary saving, pushing down the real interest rate. If this effect is strong enough, the real rate becomes negative, which implies inflation when the nominal interest rate is stuck at zero.

Figure 2. Core CPI inflation rates

Note: Dashed lines denote episodes during which policy rates were below 0.5%.

Conclusion

The new models are built on the idea that inequality and income risk matter for the business cycle and long-run outcomes. While still in their infancy, they show promise in addressing the concerns voiced by Janet Yellen and bringing about a shift in the way that macroeconomists think about aggregate fluctuations and stabilisation policy. This column only scratches the surface of the insights that can be derived from the new models. In recent work, we analyse these insights more formally, using a simple, analytically tractable model (Ravn and Sterk 2016). In this work, we also analyse the amplification of aggregate technology shocks, the relation between monetary policy and financial risk premia, and the determination of aggregate unemployment in a liquidity trap.

References

Benhabib, J, S Schmitt-Grohe, and M Uribe (2002), “Avoiding Liquidity Traps,” Journal of Political Economy, 110 (3), pp.535-563.

Challe, E, J Matheron, X Ragot, and J F Rubio Ramirez (2016), “Precautionary Saving and Aggregate Demand”, Quantitative Economics, forthcoming.

Hansen, A (1938), Full Recovery or Stagnation?, New York: W W Norton and Company.

Kaplan, G, B Moll, and G L Violante (2016), “Monetary Policy According to HANK”, manuscript, University of Chicago.

Mertens, K, and M O Ravn (2014), “Fiscal Policy in an Expectations-Driven Liquidity Trap,” Review of Economic Studies, 81(4), 1637-1667.

Ravn, M O, and V Sterk (2012), “Job Uncertainty and Deep Recessions,” Discussion paper 1501, Centre for Macroeconomics.

Ravn, M O, and V Sterk (2016), “Macroeconomic Fluctuations with HANK and SAM: An Analytical Approach,” CEPR Discussion Paper no 11696.

Summers, L (2014), “Secular Stagnation? The Future Challenge for Economic Policy,” Institute for New Economic Thinking, Toronto, 12 April.

Yellen, J (2016), “Macroeconomic Research After the Crisis”, speech At "The Elusive 'Great' Recovery: Causes and Implications for Future Business Cycle Dynamics", Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 14 October.