Credit constraints are critical barriers to growth and development (Banerjee and Duflo 2014). Yet we know surprisingly little about what factors created the differences in financial development that we see, and even less about what determines financial development over time. In a new paper (Suesse and Wolf 2020), we consider how access to credit in poor rural areas would evolve in the absence of subsidies, or public ownership, and under a minimal regulatory framework.

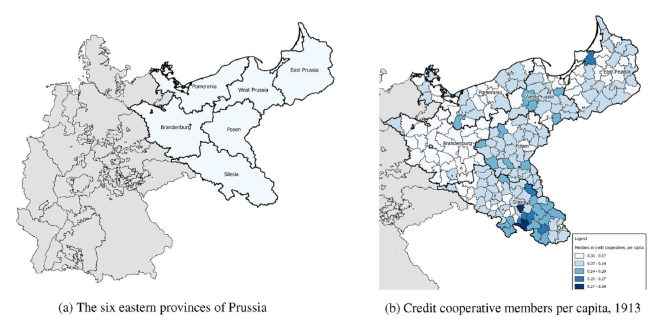

We choose a setting that is as close as possible to a free-market benchmark scenario: the rapid spread of credit cooperatives in rural 19th-century Germany. These cooperatives provided small-scale savings and loan services to previously unbanked people. Crucially, they were owned by their members, did not receive subsidies, and were subject to a minimal regulatory framework (the changes in which we can control for) (Guinnane 2002). Because this was the de novo creation of an entire system of microcredit, we can observe most independent variables before the appearance of microfinance institutions, mitigating simultaneity bias. Figure 1 shows the eastern provinces of Prussia, long dominated by agriculture, and the number of credit cooperatives per capita in 1913.

Figure 1 Credit cooperatives in the eastern provinces of Germany, 1913

Source: Suesse and Wolf (2020).

A microcredit framework

To guide our empirical work, we use a simple, flexible theoretical framework. Peasants have a choice between two types of products that differ in their capital intensity, for example grain and dairy. An exogenous change in relative prices in favour of the capital-intensive good would increase the demand for credit because farmers seek to shift production. But peasants have little collateral, and so they are credit-constrained. In this case, they can form a credit cooperative and pool assets to either access external credit from a bank, or lend to each other.

This implies that average asset size in a region should have a hump-shaped effect on cooperative formation: at one end, poor peasants have nothing to pool; at the other, rich peasants do not need to pool anything to access bank credit. The prevailing bank interest rate for peasants without credit constraints would be a floor for the cost of capital. Finally, asset inequality among peasants in a region would hinder the emergence of cooperatives, because it reduces the fraction of the population willing and able to join them.

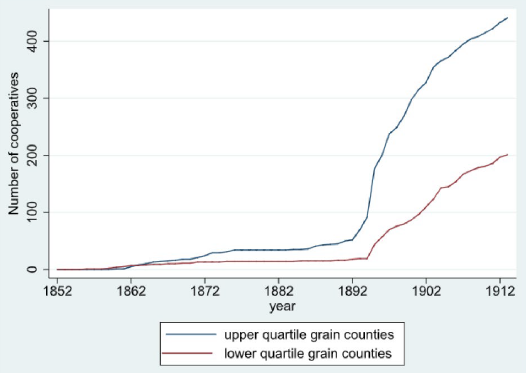

These theoretical predictions are strongly and robustly supported by our data on the emergence and spread of credit cooperatives across the 236 eastern counties of the German Empire between 1852 and 1913. The emergence of credit cooperatives over time was caused by a dramatic decline in the profitability agricultural staples. Regions more exposed to international competition in grain production experienced earlier and stronger growth when there were more credit cooperatives, other things equal. This is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Formation of credit cooperative and exposure to grain

Source: Suesse and Wolf (2020).

Once we take into account that average asset sizes (captured by farm sizes) were different in different regions, and there was asset inequality between peasants in the same region, we can explain both the timing and the extent of credit cooperative formation before 1914. The model has even more explanatory power when we control for exogenous variation in bank lending rates, in line with our theoretical prediction.

Are the empirical results causal?

We use a range of instrumental variables for both the time-varying and cross-sectional variables to make sure that our findings are more than correlations. The dynamics of grain prices in Germany can be instrumented with US prices for wheat and rye. German bank rates can be instrumented using UK interest rates. Asset inequality (in terms of farm sizes) is instrumented with the location of military strongholds of the Teutonic Order, exploiting the unique history of settlement of the eastern provinces. All our findings are robust to this.

The relative decline of grain prices in the second half of the 19th century was a powerful driver. The rapid decline in the profitability of grain production caused peasants to demand more credit, and triggered the formation of credit cooperatives: one standard deviation decrease in grain prices caused the growth rate of credit cooperatives to increase by a factor of 0.66.

Asset size also played a large role: a one-standard-deviation increase in farm size almost doubled the growth of cooperatives.

Asset inequality has only limited variation in our sample, so we run counterfactuals to extract its role. If we set land inequality to the (much lower) level in western parts of Germany, we find non-trivial effects. In particular, the most unequal districts (the province of Posen) would have 50% more credit cooperatives.

Figure 3 summarises our results. The benchmark model, which includes grain prices, interest rates, and policy dummies as the principal time-varying determinants as well as controls for cross-sectional variation, closely matches the actual growth of credit cooperatives.

Figure 3 Data and model, 1852-1913

Source: Suesse and Wolf (2020).

Did credit cooperatives aid rural transformation?

Cooperatives helped shift investment within agriculture away from staple grains towards more capital-intensive products – notably the production of meat and dairy. The Prussian cattle censuses for 1868 and 1906 show that the increase in the number of credit cooperatives is robustly correlated with an increase in animal farming, including dairy cattle, for the 236 counties in our sample. One additional credit cooperative is associated with 130 additional heads of dairy cattle during the sample period, and with more than additional 400 pigs.

Note that these results are robust to controlling for a wide range of covariates, including 1868 livestock levels, urbanisation, income and population growth. Interestingly, we find little evidence that credit cooperatives stalled structural transformation in the wider economy – for example, they did not hinder the emigration of workers from counties where they were active in industrial employment.

The impact of microcredit

We have presented a scenario with two production sectors available to farmers, with sector profitability trending in opposite directions. It follows, that microcredit uptake would only occur in a limited timeframe, when sector profits are close enough for switching to be feasible. In this setting there is likely to be a market demand for medium-term loans rather than short-term finance.

If microcredit allows farmers to exit a declining sector, a comparison between their pre- and post-credit incomes will not necessarily reveal the 'impact' of microfinance on income. Changes in the sector of economic activity would be a more relevant outcome metric. So microfinance may be better understood as helping people to adapt to a changing environment (Goodspeed 2016) or broadening their choices (Banerjee et al. 2015), rather than as a way for rural populations to escape poverty.

References

Banerjee, A and E Duflo (2014), “Do Firms Want to Borrow More? Testing Credit Constraints Using a Directed Lending Program”, The Review of Economic Studies 81(2): 572-607.

Banerjee, A, D Karlan, J Zinman (2015), "Six Randomized Evaluations of Microcredit: Introduction and Further Steps", American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7(1): 1-21.

Goodspeed, T (2016), “Microcredit and adjustment to environmental shock: evidence from the great famine in Ireland", Journal of Development Economics 121: 258-277.

Guinnane, T (2002), “Delegated monitors, large and small: Germany’s banking system 1800-1914”, Journal of Economic Literature 40(1): 73-124.

Suesse, M and N Wolf (2020), "Rural Transformation, Inequality and the Origins of Micro-Finance", forthcoming in Journal of Development Economics.