Before it was contested, there were two interesting – but different – views about the recent political election in Italy. The Economist (2012) had defined the elections as a test of the maturity and realism of Italian voters. The advice was that Italians should vote for Monti. On the other hand, the Paul Krugman in The New York Times (2013) had suggested that the Italian elections could be seen as a test for the impact of failed austerity policies: should Italians not vote for Monti, then failure would be guaranteed. There is evidence for a third possible test: one on the lack of confidence in political institutions themselves. It could explain why demagogy has emerged as the real winner of Italian elections.1

Evidence

When a country languishes in political turmoil, financial markets respond quickly. Spreads on interest rates as well as credit default swaps become higher and more volatile. Similarly, the political situation may also affect citizens’ sentiments. I offer evidence based on:

- The peculiar situation in Italy over the last two years;

- Data from household surveys.

Measures of consumer attitudes might, inter alia, contain useful indications about the general feeling on the economic system. Since these can be easily thought of as depending on the political situation, a connection between people’s sentiments and political disorder can emerge. In fact, consumers’ moods may incorporate their estimates of the impacts of rare or unique shocks, whose effects cannot be directly estimated from past experience or economic data. Such events might include both economic, e.g. the introduction of the euro, and extra-economic factors, such as psychological biases (Bovi 2009), earthquakes or political issues. A unique dataset from the European Commission helps us dig into individuals’ perceptions of their economic situations. The dataset is based on monthly surveys from the Joint Harmonised EU Programme of Business and Consumer Surveys (European Commission 2007). Respondents are interviewed during the first ten working days of each month and face ex ante and retrospective questions on several personal-level and system-wide economic topics (e.g. ‘How has the financial situation of your household changed over the last 12 months?’, ‘How do you expect the general economic situation in the country to develop over the next 12 months?’, etc.). Four indexes (2005=100, where larger values are equal to ‘better mood’) are then computed from the answers in order to capture the sentiment about the ‘current’, the ‘future’, the ‘personal’ and the ‘general’ economic stance.

Italian political crises

The last two political crises in Italy have some intriguing features in the sense that one can think they have generated two comparable shocks on Italians’ attitudes. The crises have been very close to each other: one on November 2011, the other on December 2012.

For one month preceding each crisis, most citizens were not aware of what was happening. In fact, messages sent by politicians were reassuring. Berlusconi’s declaration of his resignation was, unsurprisingly, by far the most important piece of news coming out of Italy since the Eurozone crisis began. Specifically, both crises quickly become ‘common knowledge’ during the second week of the month. To the extent these political crises have affected citizens’ dispositions, it seems that these two ‘crisis months’ created ‘abnormal’ values in the time series sentiment indexes.

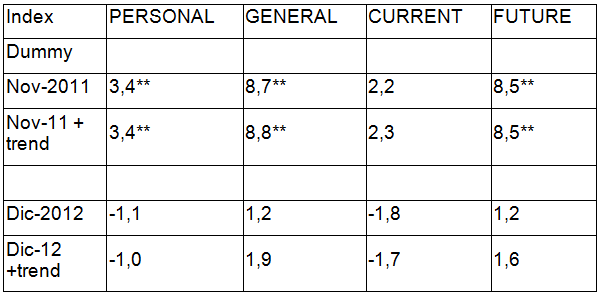

One standard way to check this is to model the consumers’ sentiment index using an ARIMA regression model and to test whether a dummy, equal to one in the month of the crisis and zero elsewhere, turns out to be significant. The following table collects the results of this exercise.

Table 1. The effect of political shocks on Italians’ sentiment

Note: Reported values are the coefficients (%) of the dummies. Four equations system, one for each index: log(index) = const +dummy +ARIMA(2,0,0). Residuals pass usual diagnostics. In the second and last row are reported the results when a (significant) linear trend is added. ** = significant (5%). Sample: Jan 1995-Dec 2012. Estimation method=SUR.

Results

Table 1 informs us that all the dummies relative to the first crisis are positive and significant. That is, when comparing the situation before and after the end of Berlusconi’s government, the sentiment of the representative Italian citizen was more positive. This is not the case for Monti’s resignation.

One cannot definitively rule out that the dummies capture the presence of events different from the political crises. But, that said, the remarked peculiarity of these two sudden crises could reduce identification issues.

These results also show other features that further increase the confidence in our findings:

- First, coefficients remain rather constant both with and without the deterministic trend;

- Second, one can note that the only index that is not affected by Berlusconi’s decision to quit is ‘current’;

In the light of the proposed interpretation of the events, this is an expected outcome. In fact, this measure captures the attitude over the last 12 months and it is hard to think that an abrupt political crisis may affect what people think about the previous year;

- By the same token, one can add that the larger elasticity shown by the indexes ‘future’ and ‘general’ is not surprising;

In fact, a political crisis should be a contingency especially impinging on macroeconomic perspectives rather than individual situations. The outcomes reported in Table 1 confirm this view. In sum, there is a small probability that another event, different from the unexpected government’s decision to resign, occurred exactly around November 2011 and such that it generated the same results.

Conclusions

These results suggest that Italians’ views about economy-wide evolutions was affected differently by two political shocks. While they were more confident after Berlusconi’s resignation, Monti’s abdication did not produce the same positive jump in people’s mood. In fact, Italians seemed not to react at all in the more recent crisis, perhaps suggesting that they are simply becoming disillusioned. Rather than a test on realism or on austerity, recent political elections could be read as a test of disaffection for political institutions. The recent wave of populism suggests that political alienation in Italy is widespread.

Author's note: The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

References

Bovi, M (2009), “Economic versus Psychological Forecasting. Evidence from Consumer Confidence Surveys”, Journal of Economic Psychology, 30(4) 563–574.

European Commission (2007), "The joint harmonised EU programme of business and consumer surveys", User Guide, DG Economic and Financial Affairs.

Krugman, Paul (2013), “Austerity, Italian Style”, The New York Times, 24 February.

The Economist (2012), “Will Mario Monti's government fall?”, 6 December.

1 I have addressed the issue of institutional failures in my previous post on 2nd December 2011.