Saving and investment, like the chicken and the egg, involve circular causality. But regardless of causality, there is no doubt that Latin America and the Caribbean need more of both.

That the region has an infrastructure problem hardly requires an explanation:

- There is a gap in terms of the quality and quantity of the stock of physical infrastructure in Latin America and the Caribbean compared with:

- The region’s needs.

- The advanced economies.

- The emerging Asian countries.

The infrastructure gap is visible in:

- Deficient transportation and communication networks.

- Low capacity to generate energy to meet growing demand.

- Poor water and sanitation services.

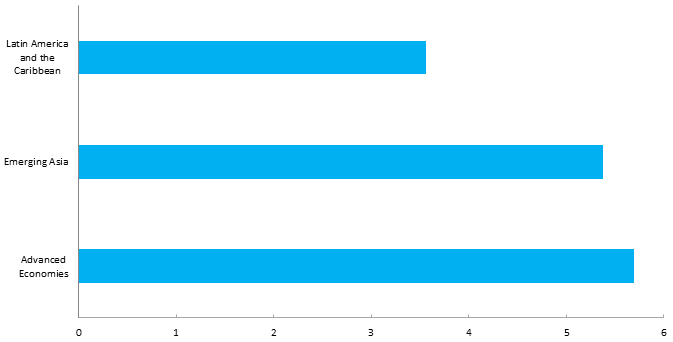

According to the latest World Economic Forum’s latest Global Competitiveness Report, on a scale of 1 (worst) to 7 (best), the quality of infrastructure in the region is 3.6, while in emerging Asia the figure is 5.4 and even higher in advanced countries.

Investment

The countries of Latin America and the Caribbean invest on average only 2.5% of GDP per year in infrastructure. This is not enough to improve the quantity and quality of capital stocks. If the investment rate were doubled, the long-term rate of economic growth could be accelerated by an estimated two percentage points per year (Calderón and Servén 2010). Moreover, if investment rates of around 4-6% of GDP could be sustained for 20 years, the infrastructure deficit that the region has in relation to emerging Asia could be eliminated (Fay and Morrison 2005).

Savings

What is less obvious is that in order to increase investment in infrastructure, domestic savings have also to increase. This is because investment in infrastructure requires long-term financing in local currency, which can only be sustained through domestic savings.

In the region, domestic savings are less than 20% of GDP, whereas in emerging Asia the figure is well above 30%. Moreover, the country that saves most in Latin America and the Caribbean saves less than the country that saves least in emerging Asia.

There are good reasons why investment in infrastructure cannot be sustainably financed by foreign savings.

- First, foreign-capital inflows tend to be volatile.

In addition, most international financing for developing countries is in a foreign currency1. These characteristics are not compatible with the type of financing required by investment in infrastructure. In fact, international evidence shows that foreign saving is not a reliable source of financing for domestic capital in developing countries (see Aizenman, Pinto, and Radziwill 2007).

- Second, although foreign direct investment is less volatile, only about 10% of it has been invested in infrastructure, which is not enough to finance investment needs.

- Third, there are complementarities between domestic and foreign savings.

Specifically, domestic saving acts as a kind of guarantee that stimulates the participation of foreign investors in infrastructure projects, that is, by saving and investing locally, residents reveal information about the quality of investment opportunities to potential foreign investors who have less information. This facilitates investments in a world of asymmetric information (See Aghion, Comin, and Howitt 2006).

- Fourth, there is evidence that in situations of low domestic savings, increased public investment tends to displace private investment, holding back the increase in total investment (See Cavallo and Daude 2011).

Figure 1. Quality of infrastructure index, 1-7 scale

Source: World Economic Forum: 2012-2013 Global Competitiveness Report

Notes: Simple average of the regions: 1 = Extremely underdeveloped; 7 = sufficient and reliable.

Advanced economies: classification World Economic Outlook.

LA: Argentina, Barbados, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Dominican Rep, Surinam, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay and Venezuela. Emerging Asia: South Korea, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan and Thailand.

Figure 2. Gross domestic saving (% of GDP)

Source: World Economic Outlook (WEO)

Notes: Advanced economies and sub-Saharan Africa: Classification WEO. Emerging Asia: South Korea, China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan and Thailand. LAC: Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Grenada, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Dominican Rep, St Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, Surinam, and Uruguay.

How to sustainably increase domestic savings

The following conclusions are drawn from the Inter-American Development Bank’s 2013 Latin American and Caribbean Macroeconomic Report (2013):

- Private saving is crucial for increasing domestic saving and for maintaining higher saving rates over time.

Government austerity alone is not sufficient unless it is accompanied by policies that promote private saving. Policymakers need to take a fresh look at the pension system reforms, the structure of tax systems and social policies, taking into account their impact on incentives for private saving.

- In Latin America and the Caribbean there is no conclusive evidence that the private sector saves inadequately, it simply does not save enough locally.

To promote private saving, countries have to adopt and persevere with prudent macroeconomic policies. Few people save voluntarily in economies that are regularly subject to extraordinary volatility, and where the real value of savings deteriorates over time.

- Fiscal policies have a role to play in promoting domestic savings.

On the expenditure side, governments can promote greater domestic saving through expenditure switching policies, which means shifting from current spending (which is too high) to capital spending (which is too low). This would be also compatible with optimal policy responses for managing extraordinary income from transitory booms in commodity prices.

- Increased pension saving would increase the availability of long-term financing in local currency, exactly the type of financing required for infrastructure investment.

Total assets managed by pension funds are increasing in many countries, but they could grow faster by reducing informality and cutting the costs of administration and participation in the funds.

- Incorporating the objective of promoting domestic saving into the policymaking process could help avoid costly mistakes.

Policies to promote domestic saving should be internally consistent. For example, the positive effects on domestic saving which might be obtained from a good pension reform could be cancelled out by the unintended consequences of other government policies in the pension area.

- Efforts to increase saving must be supplemented by mechanisms that permit domestic and foreign savings to flow into infrastructure investments.

Even if the region could miraculously increase saving overnight, cumbersome and outdated regulatory frameworks, along with the low level of bureaucratic capacity, are constraints that stand in the way of increasing investment in infrastructure.

- Finally, the quality of the investment is essential.

The most important factor in raising the quality of infrastructure investments is project selection. It is crucial to select projects with the greatest impact and, therefore, essential that countries create institutions capable of carrying out planning, adequate cost-benefit analysis, and continuous follow up and evaluation of the works.

Conclusions

Aside from the specific policies that have to be implemented, they also have to be sustained over time. To avoid the trap of low savings, countries need to create institutional capacity, strengthen the rule of law and build stable macroeconomic policy frameworks. None of these goals can be achieved overnight.

The good news is that due to the region’s greater resistance to macroeconomic volatility and low global interest rates, Latin American and Caribbean countries currently have an excellent opportunity to implement policies that stimulate domestic saving and investment in infrastructure.

References

Aizenman, Pinto, B and Radziwill, A (2007), “Sources for Financing Domestic Capital – Is Foreign Saving a Viable Option for Developing Countries?”, Journal of International Money and Finance 26(5), 682-702.

Aghion, P, Comin, D and Howitt, P (2006), “When Does Domestic Saving Matter for Economic Growth,” NBER Working Papers 12275.

Calderon and Serven (2010), “Infrastructure in Latin America”, Policy Research Working Paper 5317, World Bank.

Cavallo, E and Daude, C (2011), “Public Investment in Developing Countries: A Blessing or a Curse?”, Journal of Comparative Economics, 39(1), 65-81.

Fay, M and Morrison, M (2005), “Infrastructure in Latin America & the Caribbean: Recent Developments and Key Challenges”, Report 32640-LCR, World Bank.

Inter-American Development Bank (2013a), “Rethinking Reforms: how Latin America and the Caribbean can escape suppressed world economic growth”, coordinated by Andrew Powell, Washington DC.

1 International sovereign-bond issues in local currency are still limited. This could be due to the liquidity advantage that the US dollar and a few other global currencies continue to enjoy on financial markets. See Powell (in press).