The advantage incumbents experience in electoral races in the US is well-documented. Politicians re-running for a seat achieve re-election rates of around 90%. Incumbents are covered by the media more often and receive more endorsements compared to their opponents, and benefit from the resources of the offices they held (Levitt and Wolfram 1997). Incumbency advantage creates a tall barrier for political newcomers and challengers, and pre-empts competition (Ansolabehere and Snyder 2000, Prat 2002, Prior 2006).

At the same time, researcher have found that that new communication technologies can change voter behaviour (Falck et al. 2014, Campante et al. 2016), policy outcomes (Gavazza et al. 2015), and protest participation (Enikolopov et al. 2016, Qin et al. 2017), and it is possible that these new technologies can also help politicians to inform their constituencies and to raise money for political campaigns.

In a recent study, we analyse one channel through which newcomers in politics can overcome the barriers of communicating with voters: using online social networks (Petrova et al. 2016). Specifically, we study the impact of politicians' adoption of a new communication technology, namely Twitter, on the campaign contributions they receive. In theory, social media provide a relatively cheap technology for communicating with voters compared with traditional media, particularly for politicians who find it costly to reach out to voters to inform them about their candidacy and policies. How politicians’ adoption of online social networks influences electoral process in practice, however, remains largely unknown.

The study uses a dataset connecting the Twitter accounts of 1,814 politicians who ran for the US Congress between 2009 and 2014 to the political donations they received over this period, which are reported by the Federal Election Commission. Our analysis is focused on the personal Twitter accounts of politicians rather than accounts dedicated to a political campaign, and we only consider small amounts in political donations ($1,000 and under). This allows us to claim that the donations are more likely to come from ordinary citizens rather than lobbyists.

We compare the change in the donations received by politicians running for Congress before and after joining Twitter, exploiting the variation in Twitter usage across geographical locations relative to other websites. We refer to this variation as ‘Twitter penetration’. Twitter penetration impacts the reach of a politician’s message, and hence the financial gain she can receive upon adopting Twitter as a political communication channel.

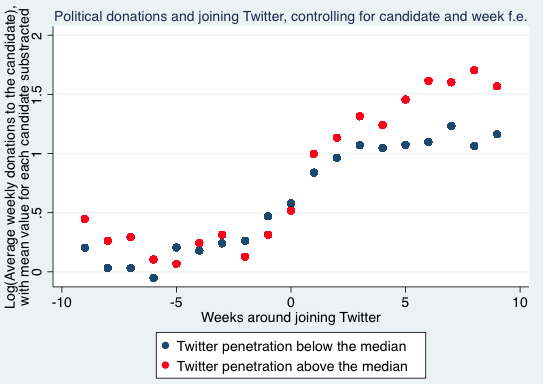

The results suggest that using Twitter helps politicians to raise more contributions, and significantly more in the areas with a higher Twitter penetration. Importantly, the increase in support is only observed for politicians who have never been elected to the Congress before, but not for the experienced candidates who have better opportunities to inform and fundraise. We find that within a month of joining Twitter, the aggregate political contributions to an average new politician increases by 1-3% of all donations under $1,000 received during a campaign. Figure 1 demonstrates the main finding of our study. There is a discontinuous increase in donations after a politician joins Twitter and the shift is higher in areas where Twitter penetration or usage is higher relative to all sites.

Figure 1. Aggregate standardised political donations received in low and high Twitter penetration areas (before and after five weeks of joining Twitter)

Our empirical strategy exploits the precise timing of opening a Twitter account by using variation in donations before and after joining Twitter and across areas of different Twitter penetration. We also include politician-month fixed effects to control for politician-specific unobserved time-varying factors, such as being more progressive-minded, more tech-savvy, or being at a different stage of campaigning.

To credibly identify the causal impact of Twitter adoption on campaign donations, several competing hypotheses must be ruled out. We specifically worry about the unobservable factors which could influence both a politician's decision to join Twitter and the donations she raises, including other campaign activities or exogenous events which coincide with the time of opening an account and vary systematically between low and high Twitter adoption regions. We test for a variety of alternative explanations to find that there is no discontinuous increase in general campaign expenditure, advertising on TV, or media and blog coverage of the politicians around the time of their Twitter entry, thus ensuring that the results are not driven by the relationship between campaign contributions and these variables.

Comparison between Twitter and other channels of political communication

How persuasive is communicating with voters over Twitter compared to the other channels of communication? We compare Twitter to other political communication and persuasion channels including direct mailing and TV advertising using the persuasion rate formula defined by DellaVigna and Gentzkow (2010). The measure summarises the percentage of receivers of a message, who change their action as a result of being persuaded by the message. We find that Twitter’s persuasion rate is around 1%, which is comparable to the persuasion rates of 1% for direct mailing (Gerber and Green 2000) and 0.1%-1% for political advertising (Spenkuch and Toniatti 2016). While Twitter’s effectiveness compares to that of direct mailing and short political ads on TV, note that the cost of advertising and direct mailing can be significantly higher compared to that of operating a personal social media account.

Mechanisms of influence: Twitter increases awareness

Why does adoption of Twitter only increase the donations received by inexperienced politicians, and not those received by the experienced ones? Communication via Twitter can – similar to advertising – both inform and persuade individuals (Nelson 1974). Specifically, information on Twitter could increase awareness of the candidates for potential donors who do not know new candidates or their policy positions and can bring new donors to the candidates. Alternatively, microblogging through Twitter may persuade those who already are aware of the candidate and can increase the size of donations.

Our findings suggest that it is more likely for Twitter communication to increase awareness of lesser known politicians among the voter base. Several findings from the study support this argument. First, we find that the increase in donations mainly comes from donors who have never donated to the candidate before and not from those who did. Second, we show that the gains are higher for candidates who are relatively lesser known by comparing the change in donations for the politicians running for the House of Representatives and for the Senate. Since every state has only two senators, and they are appointed for six years as opposed to the two-year terms of the representatives for the House, voters are likely to be more familiar with the candidates for the Senate. Backing this hypothesis, we find that politicians running for the House experience a higher shift in support than those running for the Senate.

Another piece of evidence comes from a comparison of the effect of Twitter adoption in states with substitute political communication channels. Specifically, politicians running in states with lower newspaper circulation where communication through other political channels may be more limited see a greater increase in political donations compared to politicians from states where newspaper circulation numbers are high.

Information in tweets

Since tweets only include 140 characters, a meaningful analysis of their content can be difficult. Nevertheless, through textual and sentiment analysis, it is possible to report several observations. Parsing the textual information in tweets, we find that politicians who are sending more informative messages (by including a hyperlink/URL to additional information) see higher gains from opening an account. Moreover, use of a more inclusive language (e.g. words such as “we” instead of “I”) correlates with higher gains. We also apply the linguistic inquiry and word count method (Pennebaker et al., 2015) to analyse the sentiment in tweets on emotional, social, and thinking styles1 and show that a politician with a ‘plugged in’ social style is more likely to see a greater increase in donations.

Takeaway

The election outcomes in the US are said to depend on three Ms: money, machine, and media. With political campaigns becoming increasingly more expensive, a natural concern is whether challengers have enough opportunities to communicate with the electorate and to fundraise.

The broad implication of our study is that adoption and use of social media2 offers a relatively cost-effective alternate technology to communicate with the electorate, and reduces the gap in fund-raising opportunities between new and experienced politicians, which, in turn, reduces barriers to entry to national politics and increases political competition.

References

Ansolabehere, S and J M Snyder (2000), “Old voters, new voters, and the personal vote: Using redistricting to measure the incumbency advantage”, American Journal of Political Science 44 (1), 17--34.

Campante, F, R Durante and F Sobbrio (2016), “Politics 2.0.: The Multifaceted Effect of Broabdband Internet on Political Participation”, working paper.

DellaVigna, S and M Gentzkow (2010), “Persuasion: Empirical evidence”, Annual Review of Economics 2, 643-69.

Falck, O, R Gold, and S Heblich (2014), "E-Lections: Voting Behavior and the Internet", American Economic Review 104 (7): 2238-2265

Enikolopov, R, A Makarin and M Petrova (2016) “Social Media and Protest Participation: Evidence from Russia”, CEPR Discussion Paper 11254

Gavazza, A, M Nardotto and T Valletti (2015), “Internet and politics: Evidence from UK local elections and local government policies”, CEPR Discussion Paper 10991

Gerber, A S and D P Green (2000), “The effects of canvassing, telephone calls, and direct mail on voter turnout: A field experiment”, American Political Science Review 94 (03), 653-663.

Halberstam, Y and B G Knight (2016), “Homophily, group size, and the diffusion of political information in social networks: Evidence from Twitter”, Journal of Public Economics 143, 73-88.

Levitt, S D and C D Wolfram (1997), “Decomposing the sources of incumbency advantage in the US House”, Legislative Studies Quarterly 22 (1), 45-60.

Nelson, P (1974), “Advertising as information”, Journal of Political Economy 82(4), 729-754.

Pennebaker, J W, R L Boyd, K Jordan and K Blackburn (2015), “The development and psychometric properties of LIWC2015”, UT Faculty/Researcher Works.

Petrova, M, A Sen, and P Yildirim (2016), “Social Media and Political Donations: New Technology and Incumbency Advantage in the United States”, University of Pennsylvania working paper.

Prat, A (2002), "Campaign advertising and voter welfare", The Review of Economic Studies 69 (4), 999-1017.

Prior, M (2006), “The incumbent in the living room: The rise of television and the incumbency advantage in US House elections”, Journal of Politics 68 (3), 657-673.

Qin, B, D Strömberg and Y Wu (2017), “Why Does China Allow Freer Social Media? Protests versus Surveillance and Propaganda,” CEPR Discussion Paper 11778

Spenkuch, J L and D Toniatti (2016), “Political advertising and election outcomes”, Available at SSRN 2613987.

Endnotes

[1] While the emotional categories relate to one's positive to negative emotions, social style indicates a degree of social openness and engagement, and thinking style indicates the use of logic or senses in expression of opinions.

[2] Importantly, our findings are not specific to Twitter, we find similar but slightly weaker results analysing the adoption of Facebook by politicians.