An ageing world population is expected to shape the economic future of the globe. According to UN calculations, the total world population will increase by 40% and the median age will increase by 7.8 years by 2050. Compared to a few decades ago, these rates represent a significant deceleration in population growth and a sizeable acceleration in ageing.

What do these changes imply for different economies around the world? A popular debate about this topic is heating up, as shown by a recent special briefing and front-page coverage in The Economist (2014). The argument involves two opposing views. On one hand, ageing could hinder economic growth as the old save less, which translates into higher interest rates, lower investments, and lower labour productivity. On the other hand, ageing could actually increase growth if people adapt by saving more and working longer.1

A frequently overlooked element in these discussions is that there are different types of ageing. Whether ageing is mainly driven by an increase in longevity or a decrease in fertility is important in assessing the outcomes.2 This is mainly because these two factors change incentives to save or work in different ways. These differences could be more pronounced depending on the type of social security system of a given economy as we show in Dedry et al. (2014).

To put this in to perspective, it is useful to consider the implications of demographic transition by first leaving out the changes in incentives, and associated behavioural adjustments, and focusing on accounting effects only.

An accounting approach

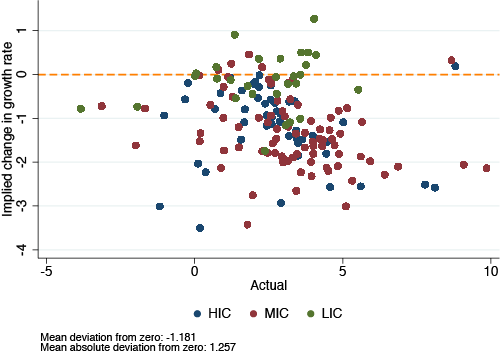

A simplistic way of demonstrating the economic impact of ageing is to use a counterfactual analysis in which historical GDP growth rates are decomposed into three components: labour productivity growth, population growth, and growth in the labour force participation rate. Next, the last two components are replaced with projections of future demographic changes (Bloom et al. 2011). A comparison between the ‘counterfactual’ GDP series and the actual one shows how a reduction in population and labour-force participation would have affected the GDP growth without a change in productivity.

Figure 1 shows that average GDP growth rate would have fallen by about 1.2 percentage points annually if demographic changes between 2010 and 2050 had already occurred between 1970 and 2010. This would translate into a near 40% decrease in GDP over 40 years. This reduction reflects both the slowdown in population growth and the increase in old-age dependency ratios. In comparison, the GDP per capita growth rates control for the change in the size of population. As a result, the growth rates would be reduced by only 0.4 percentage points annually.

The results, however, differ across countries. Whereas all high-income countries (HICs) except Estonia would have experienced a reduction in growth rates, many low-income countries (LICs) and some middle-income countries (MICs) would have benefitted from the prospective dynamics of their demographics.

Figure 1. What would demographic dynamics from 2010-2050 imply for growth rates in 1970-2010?

GDP

GDP per capita

Source: Onder and Pestieau (2014).

Taking incentives into consideration

In practice, the impact of ageing on the economy goes beyond the accounting effects. Individuals can change their behaviour to cope with the new economic reality, which can influence the economic impact of ageing significantly.

The first important behavioural adjustment can occur via savings. When people live longer, or when their incomes change due to demographic transition, they have different incentives to save. Changes in savings would, in turn, affect productivity of labour by changing the capital available per worker.

The second important behavioural adjustment can occur in labour force participation decisions. A longer life span could induce individuals to extend their active work life if retirement is not mandatory. Thus, the size of the labour force may not shrink as much as the demographic simulations show.

By holding the age of retirement and labour productivity growth constant, the counterfactual exercise above shuts down these behavioural channels. Therefore, ageing and the slowdown in population growth always bring about negative consequences in the accounting exercise. This leads to an interesting question – could behavioural adjustments overcome the negative accounting effects?

Types of ageing and social security systems matter

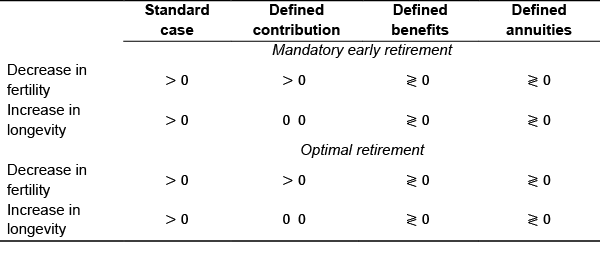

In Dedry et al. (2014), we show that behavioural adjustments may change under different types of ageing and social-security systems. To see this, it is useful to begin with a benchmark case – the well-known standard Diamond model.

When there is no social security and work after retirement, both increasing longevity and decreasing fertility rates increase the accumulation of capital.

When fertility decreases, capital per worker increases because savings do not change, but the number of workers decreases. When longevity increases, however, the increase in per-worker capital is driven by an increase in per-person savings. This adjustment is a result of consumption-smoothing motives, i.e. individuals need more saving to support themselves if they live longer.

Next, we consider work in old age under different social-security systems.

Under the defined contribution system contributions are fixed; thus, a decrease in fertility leads to a reduction in benefits. Changes in longevity, on the other hand, do not lead to any adjustments.

When fertility decreases, two things happen. First, the number of pension contributors decreases. This translates into a decrease in pension benefits. As a response, individuals save more to smooth their consumption. Second, the number of workers decreases. Therefore, as the number of workers shrinks and savings increase at the same time, the impact of a decrease in fertility rate on capital accumulation is clearly positive.

In contrast, an increase in longevity has no clear effects on capital per worker. A longer life span induces higher savings via the consumption-smoothing channel as in the previous case. However, as life span increases, individuals would also choose to work longer if retirement age were not regulated. This second adjustment could weaken or even reverse the increase in savings. Therefore, the net effect of an increase in longevity on capital per worker is ambiguous in this case.

Table 1. The impact of ageing on capital per worker under different unfunded pension systems

Source: Dedry et al. (2014).

As opposed to defined contributions, when the fertility rate changes, it is the pension contributions that adjust to satisfy the pension system balance in this case. Changes in longevity, however, do not create imbalances as in the previous case, as the benefits are paid as a lump sum – an assumption that changes under defined annuities.

When the fertility rate decreases, the first period income decreases along with increasing contribution rates. This reduces the first period income. As a result, individual savings decrease to smooth consumption. At the same time, the number of workers decreases with the reduction in the fertility rate. Overall, the net effect on capital per worker is ambiguous, because lower savings have a negative impact and fewer workers have a positive impact on capital per worker.

In the case of an increase in longevity, the outcomes are identical between defined contribution and defined benefit systems. This is mainly because the change in longevity has no effect on pension balances as the pension lump sum payment is invariant to the length of the second period. Thus, there is no adjustment via the pension contributions or benefits channels.

When the pension system is characterised by defined annuities, both increasing longevity and decreasing fertility increase the contribution ratios.

The impact of a decrease in the fertility rate on capital accumulation with defined annuities is identical with the defined benefit case. The net effect is ambiguous, and it is determined by two opposing forces: a reduction in the number of workers, which increases per-worker capital, and a reduction in per-person savings, which decreases it.

The effects of an increase in longevity are complex in the case of defined annuities. In contrast to other social security systems, an increase in life span increases the second period income in this case. With mandatory retirement, this is solely because each individual receives the annuity for a longer period.3 When individuals can choose the retirement age optimally, however, a longer work life contributes to the second period income via wage earnings as well. The increase in old age income, in turn, reduces the young generation’s incentives to save. However, savings may still increase if the annuities are small compared to first period income as a result of the need to finance a longer life span. As a result, the net effect on savings is ambiguous. Thus, the net effect on capital per worker is indeterminate as well.

Concluding remarks

The discussion above highlights the importance of considering pension system characteristics and types of ageing in assessing the economic effects of ageing. In many cases, adjustments in savings and labour force participation can potentially counter the pessimistic accounting results to a certain extent.

Finally, it is important to note that these results are concerned with long-term effects. When ageing is driven by decreasing fertility rates and the pension system has defined contribution characteristics, adjustments in savings and working life have the strongest positive effect on capital accumulation. However, dynamic simulations show that, in the short-term, a transitory decrease in utility is likely in this case.

Authors’ note: The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the World Bank.

References

Bloom, D E, D Canning, and J Sevilla (2001), “Economic Growth and the Demographic Transition”, NBER Working Paper 8685.

Bloom, D E, D Canning, and G Fink (2011), “Implications of Population Aging for Economic Growth”, PGDA Working Paper 64, Harvard University.

Dedry, A, H Onder, and P Pestieau (2014), “Aging, Social Security Design, and Capital Accumulation”, CORE Discussion Papers (forthcoming), Université Catholique de Louvain, Center for Operations Research and Econometrics.

Onder, H and P Pestieau (2014), “Is Aging Bad For the Economy? Maybe”, World Bank Economic Premise Series, 144.

The Economist (2014), “Global Ageing: A Billion Shades of Grey”, 24 April.

1 Bloom et al. (2001) provide a discussion of different approaches to the link between economic growth and demographic change.

2 The magnitude of ageing and its main drivers exhibit significant variations across different countries. Onder and Pestieau (2014) show that high-income countries (HICs) have already experienced a ‘big jump’ in the median age, whereas the middle- (MICs) and low-income countries (LICs) are expected to have such jumps within the next 40 years. Moreover, these will happen in different ways, which can be traced back to differences in fertility and longevity trends. First, compared to the last 40 years, the reduction in fertility rate will not be as dramatic in MICs, whereas it will keep decreasing significantly in LICs. Second, the increase in life expectancy at birth will slow down in both groups. However, the increase in life expectancy at the age of 60, a measure of longevity, will slow down in MICs and accelerate in LICs.

3 The analysis assumes underinvestment, i.e. the equilibrium is on the good side of the ‘golden rule’ – thus, more savings are good. Interestingly, in all cases, mandatory retirement produces more desirable outcomes than optimal retirement despite the distortions it imposes on the economy. This is mainly because forced retirement induces workers to save more than they would do under a freely chosen retirement age.