Prime Minister Abe recently announced that Japan would participate in the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations, with all other Trans-Pacific Partnership parties now having accepted Japan.1 This trade demarche is viewed as a key part of ‘Abenomics’ (Petri, Plummer and Zhai 2013). Although the dye has been cast, the debate in Japan has not ended. Many Japanese are sceptical about effects of the Trans-Pacific Partnership on the Japanese economy, so this is the right moment for research-based analysis of its economic effects.

Current estimates of the effects of the Trans-Pacific Partnership

The Japanese government disclosed their official estimate of the effect of the Trans-Pacific Partnership on GDP when Prime Minister Abe made the announcement. Based on a standard general-equilibrium model, the government forecasts Japan’s participation in the Trans-Pacific Partnership to increase its real GDP by 3.2 trillion yen, or 0.66% in its ratio to GDP (Cabinet Secretariat 2013).2 Furthermore, Petri and Plummer (2012), using their extended Global Trade Analysis Project-type model which incorporates other factors such as extensive margins of trade and foreign direct investment, estimate that Japan’s GDP in 2020 would be $95.5 billion (approximately nine trillion yen) or about 2% larger if Japan and Korea would participate in the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Growth effects of the Trans-Pacific Partnership

These estimates, however, undervalue the its effects as they only focus on the direct impacts through lowering barriers for trade and investment and thereby increasing export and foreign direct investment and, in turn, domestic production. In addition to the one-time effect on output levels, economic integration may establish effects on output growth in the medium run through higher investment returns (Baldwin 1992). Furthermore, economic integration may lead to higher long-run growth by increasing flows of ideas across borders (Rivera-Batiz and Romer 1991). Therefore, a more substantial effect of the Trans-Pacific Partnership could be through expanding social and economic networks among participating countries and thus promoting innovation and technological progress.

Networks with diverse human resources have been found to lead to innovation at the micro level. For example, productivity of researchers is shown to be the highest when they have strong ties within their specific research community as well as external ties with ‘outsiders’ who have different specialties (Rost 2011, Tiwana 2008).

Furthermore, many studies indicate that export and inward/outward foreign direct investment improves the growth rate of Japanese firms’ productivity. For example, Kimura and Kiyota (2006), based on firm-level data, conclude that a firm’s total factor productivity increases by 2.4% after it starts to export. According to my own research (Todo 2006), foreign direct investment in research and development to a given industry in Japan increases productivity of Japanese firms in the same industry through knowledge spillovers from foreign direct investment. Furthermore, Japanese firms’ foreign direct investment outflows in research and development and offshoring activities increase the productivity growth rate for their parent firms in Japan (Hijzen et al. 2010, Todo and Shimizutani 2008).

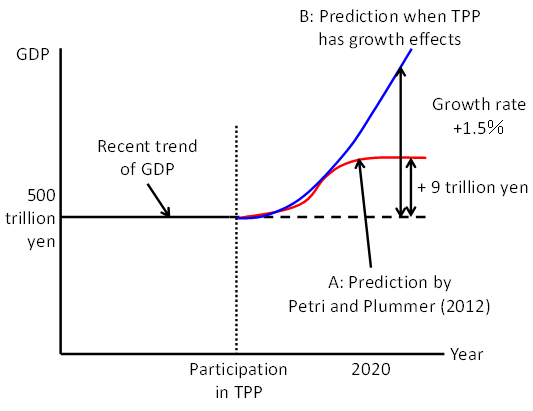

Nevertheless, it is not fully understood by Japan’s public nor policymakers that the Trans-Pacific Partnership will sustainably stimulate innovation and productivity growth, leading to an increase in the GDP growth rate and exerting significant long-term effects. As the figure below shows, according to the past estimates including those by Petri and Plummer, the Trans-Pacific Partnership will increase the absolute amount of GDP in the long run, but (without growth based on other factors) GDP will eventually stop growing and stabilise (as indicated by the red curve, A). If, however, the Trans-Pacific Partnership increases the economic growth rate by promoting innovation, GDP will continue to grow (blue curve, B). Obviously, effects on the growth rate will bring about significantly larger consequences on a cumulative basis.

Figure 1.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership will increase the growth rate of GDP per capita by 1.5%

What, then, is the extent of such growth effects? By combining Trans-Pacific Partnership’s effect on trade and foreign direct investment estimated by Petri and Plummer (2012) with the thick literature on the effect of trade and foreign direct investment on economic growth accumulated in the 1990s and 2000s, the Trans-Pacific Partnership’s effect on the growth rate of GDP per capita can be estimated.

- First, let’s look at the effect of the increase in the trade volume.

According to Petri and Plummer (2012), the Trans-Pacific Partnership will increase Japan’s trade volume (the sum of exports and imports) by $340 billion or 6.8 percentage points in its ratio to GDP in 2020. According to the estimate by Lee et al. (2004), an increase in the trade share (the ratio of the trade volume to GDP) by one percentage point will increase the growth rate of GDP per capita by 0.027 of a percentage point. Accordingly, the increase in the trade volume due to the Trans-Pacific Partnership will raise the growth rate of GDP per capita of Japan in 2020 by 0.18 of a percentage point (that is, 6.8 multiplied by 0.027). This increase is significant given the nearly 0.8% growth rate in Japan’s real GDP per capita over the past 20 years.

- Second, an even larger effect would be expected with an increase in foreign direct investment to Japan.

Petri and Plummer (2012) estimate that the Trans-Pacific Partnership will increase foreign direct investment to Japan by $155.6 billion or 3.1 percentage points in its ratio to GDP. According to Alfaro et al. (2004), inward foreign direct investment increases the growth rate of GDP per capita, and the effect is larger for countries with a more developed financial system. When the ratio of inward foreign direct investment to GDP increases by one percentage point, the growth rate of GDP per capita increases by 0.78 percentage point times the ratio of private credits to GDP in logs. Given that the ratio of private credits to GDP for Japan in 2010 was 1.72 (World Bank’s World Development Indicators), the increase in foreign direct investment to Japan due to the Trans-Pacific Partnership would increase the growth rate of GDP per capita by around 1.3 percentage points.

- Combining the effects of trade and inward foreign direct investment, the growth rate of GDP per capita will increase by 1.5 percentage points;

With the average growth rate of Japan’s real GDP per capita over the past 20 years at 0.8%, the Trans-Pacific Partnership could possibly lead to a growth rate exceeding 2%. Thus, participation in the Trans-Pacific Partnership could become the key policy measure for Japan’s economic growth.

Some reservations and conclusions

We may have to interpret these estimates with caution for the following three reasons:

- First, the results above are based on the point estimates, ignoring confidence intervals.

- Second, although this article employs the results from seminal papers in the literature on the effect of trade and foreign direct investment on growth, other studies reached different results using different methods and/or data.

- Finally, the estimate by Petri and Plummer (2012) on the effect of the Trans-Pacific Partnership on trade and foreign direct investment will have different outcomes with different assumptions in the model.

Taking these factors into account, the Trans-Pacific Partnership’s growth effects should be considered to have a significant range. However, even assuming the lowest limit of the 95% confidence interval of the estimates of Lee et al. (2004) and Alfaro et al. (2004), and assuming further that Petri and Plummer (2012) overestimated the increases in trade and foreign direct investment volumes as being twice as large, the Partnership would still increase the growth rate of GDP per capita by 0.24 of a percentage point. This would still be a sufficiently significant effect for Japan whose recent growth rate has been 0.8%.

Furthermore, the macro analysis in Section 3 and the micro analysis in Section 2 do not seem to be inconsistent with each other. Kimura and Kiyota (2006) demonstrated that starting to export increases the growth rate of the firms’ total factor productivity by 2.4 percentage points on average. As the Trans-Pacific Partnership would lead to an increase in the number of exporting firms by prompting non-exporters to become exporters, the estimate of this article that the growth rate of GDP per capita increases by 0.18 percentage point through an increase in the trade volume would be reasonable. Also, Todo (2006) demonstrates that spillovers of knowledge and technology associated with foreign direct investment into Japan improve the productivity of Japanese firms in average industries by 4%. Thus, it is not surprising if increasing foreign direct investment to Japan due to the Trans-Pacific Partnership raises the growth rate by approximately 1.3 percentage points.

The estimated result that the Trans-Pacific Partnership will increase the growth rate of GDP per capita by 1.5 percentage points through promoting innovation may not be necessarily inaccurate. Furthermore, although we should interpret the estimates allowing for a sufficient range, its effect, even using a low estimate, will still provide sufficiently significant growth effects for Japan.

It should be emphasised, however, that the estimate is based on an assumption that the Trans-Pacific Partnership is completed without exceptions to the liberalisation of trade and foreign direct investment. The more there will be of exceptions and regulations in the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the less trade and foreign direct investment between participating countries will be resulted in, thus the smaller the effects of the Trans-Pacific Partnership. According to Petri et al. (2011), in the case that each participating country is allowed to have exceptions in three sectors, one-quarter of the Trans-Pacific Partnership-generated increase in Japan’s GDP would diminish. Therefore, it is in national interests of participating countries, including Japan, that the governments will not set excessive exceptions so that they can benefit as much as possible from the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Editor's Note: A longer version of this column was published in Japanese on March 12, 2013 on the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry website.

References

Alfaro, Laura, Areendam Chanda, Sebnem Kalemli-Ozcan, and Selin Sayek (2004), "FDI and Economic Growth: The Role of Local Financial Markets", Journal of International Economics 64(1), 89-112.

Baldwin, Richard (1992), “Measurable Dynamic Gains from Trade”, Journal of Political Economy 100(1), 162-174.

Cabinet Secretariat of Japan (2013), “Kanzei Teppai Shita Baaino Keizai Kokani tsuiteno Seihu Toitsu Shisan (The Estimate of the Government on the Economic Impact of Trade Liberalization)”, available at (in Japanese).

Hijzen, Alexander, Tomohiko Inui, and Yasuyuki Todo (2010), “Does Offshoring Pay? Firm-Level Evidence from Japan”, Economic Inquiry 48(4), 880-895.

Kimura, Fukunari and Kozo Kiyota (2006), “Exports, FDI, and Productivity: Dynamic Evidence from Japanese Firms”, Review of World Economics 142(4), 615-719.

Lee, Ha Yan, Luca Antonio Ricci, and Roberto Rigobon (2004), "Once Again, Is Openness Good for Growth?", Journal of Development Economics 75(2), 451-72.

Petri, Peter and Michael G Plummer (2012), “The Trans-Pacific Partnership and Asia-Pacific Integration: Policy Implications”, Peterson Institute for International Economics Policy Brief, refer to http://asiapacifictrade.org/ for more detailed results.

Petri, Peter, Michael G Plummer, and Fan Zhai (2011), “The Trans-Pacific Partnership and Asia-Pacific Integration: A Quantitative Assessment”, East-West Center Working Paper Economics Series, 119.

Petri, Peter, Michael G Plummer and Fan Zhai (2013), “Japan’s ‘Third Arrow’: Why Joining the TPP is a Game Changer”, blog, Peterson Institute for International Economics, 15 March.

Rivera-Batiz, Luis A and Paul M Romer (1991), “Economic Integration and Endogenous Growth”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 106(2), 531-555.

Rost, Jatja (2011), “The Strength of Strong Ties in the Creation of Innovation”, Research Policy, 40, 588-604.

Tiwana, Amrit (2008), “Do Bridging Ties Complement Strong Ties? An Empirical Examination of Alliance Ambidexterity”, Strategic Management Journal 29, 251-272.

Todo, Yasuyuki (2006), "Knowledge Spillovers from Foreign Direct Investment in R&D: Evidence from Japanese Firm-Level Data", Journal of Asian Economics, 17(6), 996-1013.

Todo, Yasuyuki and Satoshi Shimizutani (2008), “Overseas R&D Activities and Home Productivity Growth: Evidence from Japanese Firm-Level Data”, Journal of Industrial Economics, 56(4), 752-777.

1 For some governments, the assent needs to be confirmed by national parliaments.

2 The simulation used the Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP) model.