A Friedman-type experiment helps a lot to illustrate the welfare implications of capital flight. Think of the owner of Spanish government bonds. Worried about default, she might want to leave the country and invest in safe assets abroad. Suppose she would put them in a backpack, take the train to Frankfurt and deposit her bonds in the safe. Then, there would be no welfare implications in either Germany or Spain. But the capital flight was also not successful from the investors’ perspective. Upon arrival, she will still find government bonds in her backpack – and become aware that she cannot trade them into German Bunds in Frankfurt either without realising substantial losses.

Alternatively, the investor might give the government bonds to the central bank of Spain as collateral via the banking system, in return for fresh Euros that are “printed” electronically. These newly printed Euros can be wired via the TARGET2 system to Germany and deposited, say at Commerzbank in Frankfurt. This is more successful from the investors’ perspective. She gets rid of Spanish bonds and can now buy German ones. However, in this case, the taxpayers in both countries are involved. As owners of the Eurosystem – the European system of central banks – they have just inherited the risk of default from the investor. The transaction generates a TARGET2-imbalance among central banks; a claim for Germany and a liability for Spain1.

A shift in deposits as a reason for TARGET2 imbalances?

In a recent Vox article, Paul De Grauwe analyses these TARGET2 balances, but from a different angle – the flight of deposits in the banking system. He thinks of a Spanish saver, who simply sends her deposits to Germany. This ‘innocent’ shift of deposits2, he concludes, is of no concern for taxpayers. I will argue however, that this transaction is just the mirror image of the capital flight described above – and if it wasn’t, it is not relevant to the TARGET2 debate. Deposit flight by itself is neither necessary nor sufficient for TARGET2 imbalances to occur.

To illustrate this point, compare two more complete scenarios. The Spanish resident sends her deposits to Germany and the Spanish private bank:

- Sells some of its assets in the market to cope with the withdrawal of deposits.

- Borrows money from the central bank of Spain to avoid such selling of assets.

Note that case (A) leaves TARGET2 balances among the central banks of Germany and Spain unchanged. Moving deposits to Germany does therefore not automatically lead to a TARGET2 imbalance. In equilibrium, the German private bank could for instance buy the assets that were sold by the Spanish bank, at market prices. This was the case before 2007, where neither a crisis, nor a TARGET2 real-time settlement system existed. And it is still the case when moving deposits to other non-Eurozone countries3.

Only if the Spanish central bank gives credit to the private bank (‘prints money’) to finance this capital flight, there will be a TARGET imbalance among central banks. In this case, the assets of the Spanish private bank end up as collateral at the Bank of Spain, instead of being sold in the market.

The role of the national central banks

At the core of a welfare analysis must be the exchange between newly ‘printed’ money and non-marketable collateral-assets at the national central banks, and thus the second version of the Friedman-experiment above. The ECB has reduced collateral standards dramatically in the last years and has announced a ‘full allotment’ policy. De facto, it has performed the role as a lender of last resort to the private banks and thereby effectively insured deposits, as well as other bank liabilities.

Furthermore, the national central banks have assumed responsibility to assess the quality of collateral. Despite some haircuts4, they still give out fresh money for balance sheet components that would not be of full value in the market. In this sense, the shifting of deposits becomes an indirect exchange of Spanish and German government bonds (or other types of risky and safe assets). It is facilitated by the central banks and would not be feasible in the market.

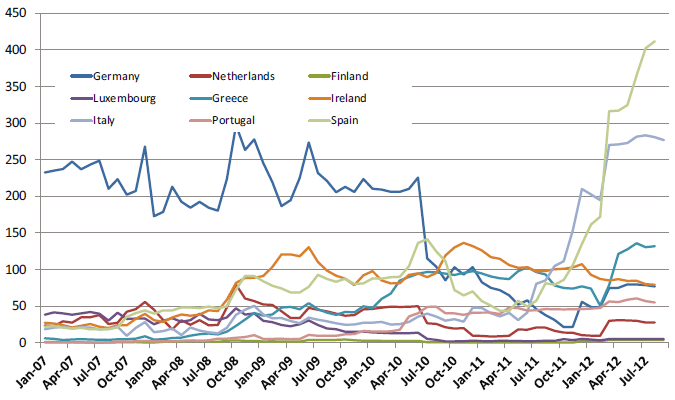

How is this different from expansionary monetary policies in other countries? As I have pointed out in a Vox article with Aaron Tornell, the TARGET2 system generates a common-pool – the Eurozone-wide demand for money. This allows the central bank of Spain to issue much more credit to its private banks, and accept much more non-marketable collateral, than it could have done if it was a country with its own currency. As a consequence, the central bank credit to private banks issued by Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain have gone up by more than 1000% since the beginning of the crisis (See Figure 1)5. It is a process that, we argue, leads to a classical tragedy-of-the-commons dilemma6.

Figure 1. Central banks’ loans to credit institutions [billion €]

Source: Euro Crisis Monitor, Osnabrueck University.

Empirical relevance

Looking at the data helps to analyse which type of capital flight is more relevant for the European case – the deposit shifting or the flight from low-quality assets. We focus on Italy and Spain, where TARGET balances mounted rather recently, and De Grauwe and Ji suspect the balances are of no concern.

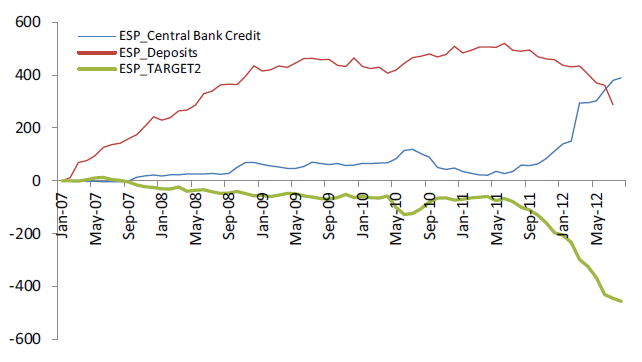

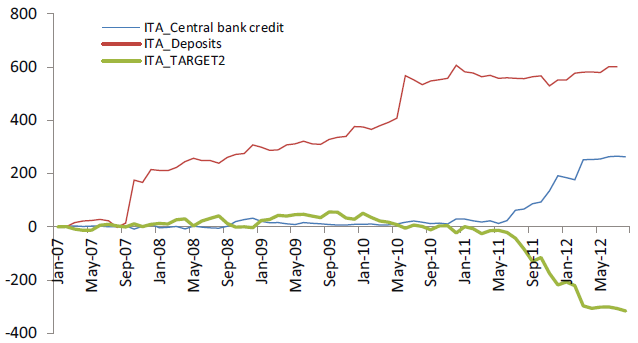

Figure 2 shows three time series for each country: central bank credit, private bank deposits, and TARGET2 balances. Each series starts at zero and displays the cumulative increment since 2007. First, looking at central bank credit and TARGET2 balances, one can see that they are nearly identical, with opposite signs. This confirms the argument above that deposit flight can only be relevant for TARGET2 balances if it is associated with a refinancing at the central bank. Furthermore, the red dashed lines show the patterns of deposits of households and firms (excluding government and MFI deposits).

In Spain, the decline in deposits starts just about the same time as the increase in TARGET2 balances, which is consistent with the conjecture of De Grauwe. But in magnitude, it is too small to explain the TARGET2 liability. Less than half of the over €400 billion TARGET2 liabilities could be explained by deposit flight7. Also, the current level of deposits is still clearly above the pre-2007 values. In Italy, the case is even clearer. Household deposits have not fallen at all. But nevertheless, Italy has accumulated more than €300b billion of TARGET2 liabilities within less than a year.

The empirical evidence thus supports the argument that deposit flight is not necessary to explain TARGET2 balances. The Italian case furthermore suggests that the Friedman-type of capital flight is present, even when no deposits are withdrawn and there is no remarkable change in the current account. It is not the existing deposits that leave, but those that were newly generated, after collateral rules were relaxed (8 December 2012) and banks borrowed from the central bank.

Figure 2a. Private bank deposits, central bank credit and TARGET2 balances in Spain since 2007

Figure 2b. Private bank deposits, central bank credit and TARGET2 balances in Italy since 2007

Note: The deposits exclude interbank credit and government deposits. 2007 is set to zero. The Graphs show the increment of each series since the beginning of the 2007/8 financial crisis.

Source: National central bank balance sheets and ECB.

Will deposit insurance help?

Large-scale deposit flight in Europe would be a serious problem. Most importantly, it would create an inefficient allocation of capital. It would also threaten to cause bank failures in the countries where the deposits leave. As shown above, however, the flight of deposits across borders is not the main source of capital flight and TARGET2 imbalances so far8. A common deposit insurance in Europe that is currently debated, might stop the type of deposit flight that Paul De Grauwe has in mind. In this regard, it could indeed be a useful tool. But how about the other type of capital flight?

The main problem in Italy and Spain is the investors’ apparent lack of confidence in government bonds and other assets of the aggregate banks’ balance sheets. To address this problem, a common deposit insurance will not help. The only reason why the flight from government bonds might stop is that structural reforms make it likely that the countries can service their debts. It is also likely that banks need to write off losses on some other assets. If their equity base is not large enough, some of them will need to be closed or merged. The ECB on the other hand, should raise its collateral standards again. This would limit TARGET2 imbalances and capital flight via the Eurosystem of central banks. It is also needed to protect the interests of the taxpayers. Without these additional measures, however, even a full banking union might not stop the capital flight.

References

Bindseil, U (2012), “Deutschland und die Target2-Salden”, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 20 February.

Carstensen, K, W Nierhaus, T O Berg, B Born, C Breuer, T Buchen, S Elstner, C Grimme, S Henzel, N Hristov, M Kleemann, W Meister, J Plenk, A Wolf, T Wollmershäuser and P Zorn (2012), “ifo Konjunkturprognose 2012/2013: Erhöhte Unsicherheit dämpft deutsche Konjunktur erneut”, ifo Schnelldienst, 65(13): 15-68

De Grauwe, P and Y Ji (2012), “What Germany should fear most is its own fear”, VoxEU.org, 18 September.

Garber, P M (1999), “The target mechanism: Will it propagate or stifle a stage III crisis?”, Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 51(1).

Sinn, H-W and T Wollmershäuser (2012), “Target Loans, Current Account Balances and Capital Flows: The ECB’s Rescue Facility”, International Tax and Public Finance, 19(4):468-508.

Schoenmaker, D and D Gros (2012), “A European Deposit Insurance and Resolution Fund”, CEPS Policy Brief No. 283.

Tornell, A (2012), “The Dynamic Tragedy-of-the-Commons in the Eurozone, the ECB and Target2 Imbalances”, UCLA, mimeo.

Tornell, A and F Westermann (2012), “The tragedy of the commons at the European Central Bank and the next rescue”, VoxEU.org, 22 June.

1 See Garber (1998) and Sinn and Wollmershäuser (2011). Note that the owner of the Spanish government bond does not need to be a Spanish resident. They could be anywhere in the world, including Germany.

2 “While prudent, it is really just foreign exchange speculation…” (De Grauwe and Ji 2012)

3 Before the crisis there was of course also (C): the Spanish private bank borrows in the interbank market.

4 See Bindseil (2012). Note however, that the haircut only limits the maximum amount of money the banks can receive from the central bank. But it is not costly for them. If banks were to instead sell the asset in the market, they would immediately realise a loss. Borrowing from the central bank helps them to delay the realisation of losses. Furthermore, although haircuts are high at the margin, the average haircut is likely to be much lower. Finally, it is not clear whether the ECB could enforce its status as a senior lender in case of insolvency. On August 2nd, for instance, Mario Draghi declared that the ECB will “address private investors issues with creditor seniority” of the ECB in the context of the bond-purchase programme.

5 Data on central bank credit and current TARGET2 balances are regularly updated on Osnabrueck’s Euro-Crisis web-page: www.eurocrisismonitor.com

6 See Tornell (2012) for a formal analysis.

7 Even this decline in deposits may have nothing to do with the TARGET2 imbalance, as investors could also withdraw funds to spend within the country. Carstensen et al (2012) point out that an international deposit flight of private households would show up in the balance of payments. So far, however, there are only noticeable changes in the statistics for banks, not households.

8 See Schoenmaker and Gros (2012) and recent proposals of the EU commission