Because of its size and interconnectedness, developments in the US economy are bound to have important effects around the world. The US has the world’s single largest economy, accounting for almost a quarter of global GDP (at market exchange rates), one-fifth of global FDI, and more than a third of stock market capitalisation. It is the most important export destination for one-fifth of countries around the world. The US dollar is the most widely used currency in global trade and financial transactions, and changes in US monetary policy and investor sentiment play a major role in driving global financing conditions (World Bank 2016).

At the same time, the global economy is important for the US as well. Affiliates of US multinationals operating abroad, and affiliates of foreign companies located in the US account for a large share of US output, employment, cross-border trade and financial flows, and stock market capitalisation. Recent studies have examined the importance of global growth for the US economy (Shambaugh 2016), the global impact of changes in US monetary policy (Rey 2013), or the global effect of changing US trade policies (Furman et al. 2017, Crowley et al. 2017).

It is likely that there will be shifts in US growth, monetary and fiscal policies, as well as uncertainty in US financial markets. What will be the global spillovers? Our recent work (Kose et al. 2017) attempts to answer these questions:

- How synchronised are US and global business cycles?

- How large are global spillovers from US growth and policy shocks?

- How important is the global economy for the US?

How synchronised are US and global business cycles?

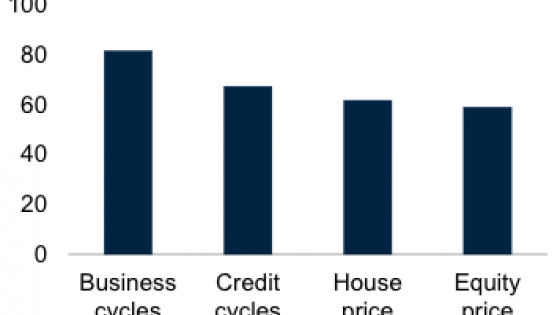

Business cycles in the US, other advanced economies (AEs), and emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) have been highly synchronous (Figure 1.A). This partly reflects the strength of global trade and financial linkages of the US economy with the rest of the world, but also that global shocks drive common cyclical fluctuations. This was particularly the case at the time of the 2008-09 Global Crisis. It is not a new phenomenon, however. Although the four recessions the global economy experienced since 1960 (1975, 1982, 1991, and 2009) were driven by many problems in many places, they all overlapped with severe recessions in the US (Kose and Terrones 2015).

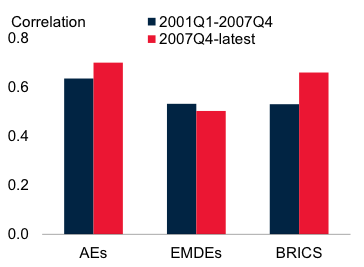

Other countries tend to be in the same business cycle phase as the US roughly 80% of the time (Figure 1.B). The degree of synchronisation with US financial cycles is slightly lower, but still significant – credit, housing, and equity price cycles are in the same phase about 60% of the time. Although it is difficult to establish empirically whether the US economy leads business and financial cycle turning points in other economies, recent research indicates that the US appears to influence the timing and duration of recessions in many major economies (Francis et al. 2015).

Figure 1 Synchronisation of business cycles

A. Correlations with US business cycles

Sources: Haver Analytics; World Bank; Kose and Terrones (2015); IMF.

Notes: Contemporaneous correlations between cyclical component of US real GDP and cyclical component of real GDP of advanced economies and EMDEs.

B. Concordance with US business and financial cycles

Sources: Haver Analytics; World Bank; Kose and Terrones (2015); IMF.

Notes: Average share of years in which business cycles in the US and all economies were in the same phase. A higher share suggests more synchronization between two countries.

How large are global spillovers from US growth and policy shocks?

A surge in US growth – whether due to expansionary fiscal policies or other reasons – could provide a significant boost to the global economy. Shocks to the US economy transmit to the rest of the world through three main channels.

- An acceleration in US activity can lift growth in trading partners directly through an increase in import demand, and indirectly by strengthening productivity spillovers embedded in trade.

- Financial market developments in the US may have even wider global implications. US bond and equity markets are the largest and most liquid in the world and the US dollar is the currency mostly widely used in trade and financial transactions. This makes US monetary policy and investor confidence important drivers of global financial conditions (Arteta et al. 2015, IMF2015).

- Given its role in global commodity markets (the US is both the world’s largest gas and oil consumer and producer), changes in US growth prospects can affect global commodity prices. This affects activity, fiscal and balance of payment developments in commodity exporters.

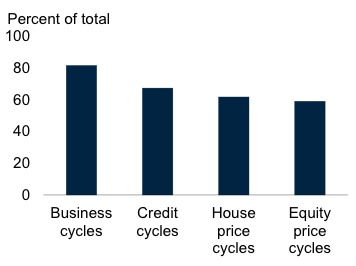

Estimates indicate that a percentage-point increase in US growth could boost growth in advanced economies by 0.8 of a percentage point, and in emerging market and developing economies by 0.6 of a percentage point after one year (Figure 2.A). Investment could respond even more strongly. A boost to investment could come for instance from fiscal stimulus measures – but the effect would largely depend on the circumstances of the implementation of these measures, including the amount of remaining economic slack, the response of monetary policy, and the adjustment of household and business expectations to the prospect of higher deficit and debt levels. A faster tightening of US monetary policy than previously expected could, for instance, lead to sudden increases in borrowing costs, currency pressures, financial market volatility, and capital outflows for more vulnerable emerging market and developing economies.

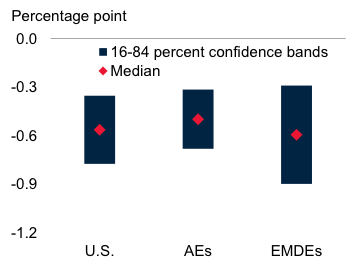

Even in the absence of actual policy changes, heightened uncertainty driven by financial market volatility or ambiguity about the direction and scope of US policies could discourage investment both in the US and in the rest of the world. Empirical estimates suggest that a sustained 10% increase in US stock market volatility (specifically, the VIX) could, after one year, reduce investment growth in the US by about 0.6 of a percentage point, in other advanced economies by around 0.5 of a percentage point, and in emerging market and developing economies by 0.6 of a percentage point (Figure 2.B).

Figure 2 US growth and uncertainty spillovers

A. Growth spillovers

Sources: Haver, Bloomberg, World Bank estimates.

Notes: Cumulative impulse responses of GDP growth in other advanced economies (AEs) and EMDEs to a percentage-point increase in growth in real GDP in the US. Growth spillovers are based on a Bayesian vector autoregression model. The sample for other AEs includes Eurozone (19 countries), Canada, Japan, and the UK and 19 EMDEs for 1998Q1-2016Q2.

B. Uncertainty spillovers on investment growth

Sources: Haver, Bloomberg, World Bank estimates.

Notes: Cumulative impulse responses after one year of investment growth in the US, 23 other AEs, and 18 EMDEs to a 10% increase in the US VIX. Vector autoregressions were estimated for 1998Q1-2016Q2 with two lags.

How important is the global economy for the US?

Important as the US is to the global economy, the US economy is also affected by its trade and financial linkages with the rest of the world. Global economic developments play an important role in driving activity and financial markets in the US.

US multinationals account for a large share of US output and labour productivity growth, and their presence in financial markets is large. In turn, foreign multinationals operating in the US provide a large share of US employment and exports (Figure 3.A).

Much of the global value chain activity is conducted through US multinational corporations and their affiliates abroad. Overall, one-quarter of US exports represents US value added embedded in other countries' exports. This ‘forward participation’ is particularly high in chemicals, business services, and electronics, and with China, Canada, and Mexico. ‘Backward participation’ is more limited: the average import content of US exports was 13% in 2014, well below the average for other advanced economies (27%). This interconnectedness is an important source of spillovers between the US and the global economy.

As a result, growth setbacks originating in other economies, or policy changes affecting market access of US companies, can have detrimental effects on the US. These effects are particularly noticeable in the more globally integrated manufacturing sector (Figure 3.B).

Figure 3. Importance of the global economy for the US economy

A. Role of foreign multinational corporations in the US

Sources: Bureau of Economic Analysis, World Bank estimates.

Notes: Share of multinational corporations in US sales, exports and imports of goods and employment. "Sales" indicates sales of multinational corporations in gross output of US private sector industries. Data covers 2010-2013.

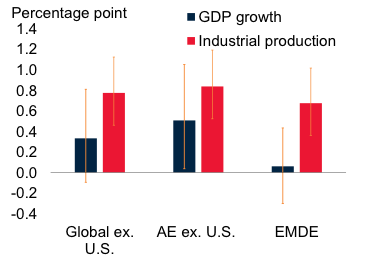

B. Spillover to US from 1 percentage point increase in global, advanced economy, and emerging market and developing economy growth

Sources: Bureau of Economic Analysis, World Bank estimates.

Notes: Cumulative impulse responses after one year of GDP or industrial production (IP) growth in the US following a 1 percentage point increase in GDP or industrial production growth in 22 other AEs and 19 EMDEs (13 EMDEs for industrial production). ‘Global’ indicates the weighted average impact of AEs and EMDEs. Vertical lines indicate 16th-84th percentile confidence bands. Vector autoregression models are estimated for 1998Q1-2016Q2 with four lags.

Acceleration or uncertainty?

Given its size and the strength of its ties with the global economy, shocks to the US economy are transmitted globally through many channels. On the one hand, an acceleration in US growth could be expected to have positive effects for the rest of the world, if not counterbalanced by increased trade barriers or an unexpected tightening of global financing conditions. On the other hand, persistent policy uncertainty could hamper growth throughout the global economy, and could have particularly adverse effects on investment growth in emerging market and developing economies, which have already showed weakness in recent years (World Bank 2017).

Editor’s note: The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this article are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank, its Executive Directors, or the countries they represent.

References

Arteta, C, M A Kose, F Ohnsorge, and M Stocker (2015), "The Coming US Interest Rate Tightening Cycle: Smooth Sailing or Stormy Waters?", Policy Research Note 15/02. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Crowley, M, H Song, and N Meng (2017), “Protectionist threats jeopardise international trade: Chinese evidence for Trump’s policies”, VOXEU.org, 10 February.

Francis, N M, T Owyang and D Soques (2015), “Does the United States Lead Foreign Business Cycles?”, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 97(2): 133-158.

Furman, J, K Russ and J Shambaugh (2017), “US tariffs are an arbitrary and regressive tax”, VOXEU.org, 12 January.

IMF (2015), 2015 Spillover Report, Washington, DC.

Kose, M A, and M E Terrones (2015), Collapse and Revival: Understanding Global Recessions and Recoveries, Washington, DC: IMF.

Kose, M A, C Lakatos, F Ohnsorge and M Stocker (2017), “The Global Role of the US Economy: Linkages, Policies and Spillovers”, Policy Research Working Paper No. 7962, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Rey, H (2013), “Dilemma not Trilemma: The global financial cycle and monetary policy independence”, VOXEU.org, 31 August.

Shambaugh, J (2016), Why the United States Needs the World to Grow, Washington, DC: White House Council of Economic Advisers.

World Bank (2016), Spillovers and Weak Growth: Global Economic Prospects January 2016, Washington, DC.

World Bank (2017), Weak Investment in Uncertain Times: Global Economic Prospects January 2017, Washington.