According to many observers, housing credit markets played a key role in the US financial crisis of 2007/08 and the subsequent Great Recession (e.g. Mian and Sufi 2009). The Great Recession produced a deep contraction in the US economy. A sequence of interest rate cuts meant that the Fed ran out of options for conventional monetary policy interventions, and rolled out unconventional monetary policies that shored up housing credit markets through purchases of mortgage debt and mortgage backed securities.

Similarly, when Wall Street crashed in 1929, the early stages of the Great Depression saw the construction sector coming to a grinding halt, with the number of new housing starts plunging from a pre-depression high of 900,000 in 1925 to less than 100,000 in 1933 (Leamer 2007). The Great Depression witnessed the US experiencing a sequence of banking panics, a mortgage credit crunch, and an unprecedented foreclosure crisis, accompanied by a severe contraction.

A long history of US federal housing credit policy interventions

There was a strong belief amongst policymakers in the early 1930s that malfunctioning housing credit markets contributed significantly to the collapse of the US economy. This motivated the US government to create the housing government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) and related government agencies. This process began in 1932 with the establishment of the Federal Home Loan Bank System chartered, in the words of President Hoover, “to meet the present emergency and to build up homeownership on more favorable terms than exist today”. Thereafter followed the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation in 1933, the Federal Housing Administration in 1934, and the Federal National Mortgage Association in 1938. In 1944, the GI Bill established the Veterans Administration mortgage guarantee programme.

In reaction to credit crunches in the 1960s, Congress again turned to housing GSEs to stabilise housing credit markets. In 1968, the Federal National Mortgage Association was split into a government-retained Ginnie Mae, supporting special classes of FHA/VA mortgages, and a quasi-privatised Fannie Mae, chartered with supporting a secondary mortgage market for government-guaranteed mortgages. In 1970, Congress chartered a quasi-private Freddie Mac to support a conventional mortgage secondary market for thrifts, and Fannie was allowed to enter the conventional mortgage market.

Broadly speaking, Fannie and Freddie were tasked with stabilising the supply of housing credit across regions and time by maintaining liquid secondary mortgage markets and intervening during credit crunches and periods of economic distress (in addition to assorted affordable housing goals). In return, the GSEs have enjoyed various privileges such as authorizations to borrow from the Treasury, light prudential regulation, and preferential tax treatment. Moreover, agency securities are eligible for Federal Reserve open market operations.

A key GSE activity relates to portfolio mortgage purchases, through which they inject liquidity into the housing credit market and remove risky assets from mortgage lenders’ portfolios. This portfolio activity is profitable because of a perceived implicit government guarantee on their debt and the GSEs’ preferential tax treatment; it is also regulated, notably through capital requirements and restrictions on asset holdings, which are largely confined to certain classes of mortgages and mortgage securities.

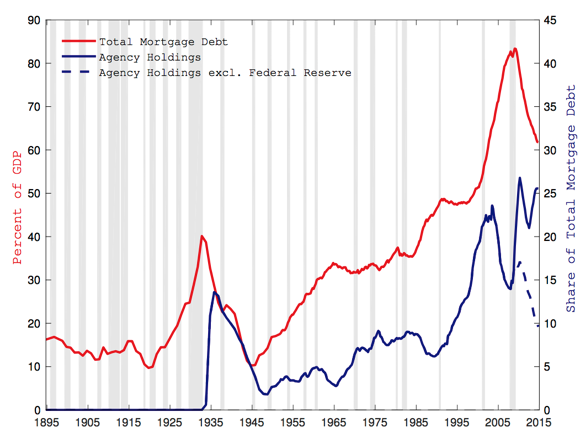

Figure 1 illustrates estimates of total US mortgage debt (as a percentage of GDP) and the share of that mortgage debt held by the housing GSEs and other government agencies. Following a rapid run-up, total mortgage debt fell sharply in the US in the 1930s, reaching a low of roughly 10% of GDP at the end of WWII. In the post-war period, mortgage debt has grown markedly, albeit at varying rates, peaking at more than 80% in 2009. Mortgage debt has declined significantly since the onset of the Great Recession, as in the Great Depression, and now hovers just above 60% of GDP.

Figure 1 Mortgage debt and agency market shares

Notes: Residential mortgage debt include home as well as multifamily mortgages. Agency holdings of both whole loans and pools. The grey bars are NBER-dated recessions.

Sources: See appendices to Fieldhouse et al. (2017).

Within six years of their first introduction in 1932, government agencies had accumulated more than 13% of outstanding US mortgage debt onto their portfolios. The GSEs subsequently established themselves as large players in the US mortgage market, gaining market share in two rapid expansions starting in the late 1960s and again in the early 1990s. By 2004 the GSEs held close to a quarter of all outstanding US mortgage debt on their portfolios, but accounting scandals then led to a tightening of Fannie Mae’s capital requirements and increased regulatory oversight, arresting their growth. Fannie and Freddie were taken into conservatorship in September 2008; today, the GSEs’ mortgage portfolios account for less than 10% of total US mortgage debt. The Federal Reserve, on the other hand, now holds another 15% of total US mortgage debt, bringing total government holdings just above their 2004 levels.

The macroeconomic effects of government mortgage asset purchases

Despite the significant role of the housing GSEs in the mortgage markets, their activities have not been subject to much scrutiny by macroeconomists. In a new paper, we pursue this task and ask how the portfolio mortgage purchase activities have affected the availability of housing credit and key aggregate variables (Fieldhouse et al. 2017). Due to the explicit stabilising role the agencies are chartered with, it is pertinent to account for endogeneity in their portfolio mortgage purchase activities. Our identification approach relies on a new narrative analysis of the legislative and regulatory history of housing agencies in the spirit of Romer and Romer (1989, 2010) and Ramey (2011) (see Fieldhouse and Mertens 2017) for details.1 We identify significant policy changes impacting the ability of Fannie, Freddie, and Ginnie to purchase mortgages, as well as more recent mortgage interventions by the Federal Reserve and Treasury. Each policy intervention is quantified and classified as cyclically or non-cyclically motivated using historical records. In practice, the GSEs conduct mortgage purchases by first signing advance purchase commitments, which are effectuated once mortgages are issued in the primary market. Accordingly, there are important ‘news’ effects related to the narratively identified interventions, which we control for by distinguishing between purchase commitments and actual purchases. The non-cyclical interventions are used as instruments for ‘exogenous’ news shocks to GSE portfolio purchases, and we estimate their impact on variables of interest using a local projection-IV strategy.

The results, all based on a monthly sample over 1967—2006, indicate a key role for the agencies in shaping the US economy. Figure 2 illustrates the impact of a one percentage point increase in the agencies’ expected purchases (as a share of trend originations) on various variables. When the agencies sign mortgage purchase commitments, it triggers a rise in mortgage originations, a delayed but steady increase in mortgage debt, and declines in conventional mortgage rates and 10-year Treasury rates. In parallel, agency mortgage purchases stimulate new housing starts which rise after 8 months. The results suggest an early increase in refinancing activity and existing home sales, followed by an increase in new home sales after a year or two. There is also some evidence of an increase in real home prices, albeit with large standard errors.

Figure 2 Impulse responses to a shock to anticipated agency purchases

Notes: The figure shows responses to a one pp. increase in the expected future agency market share measured by agency commitments as a ratio of trend originations. Estimates are from local projections-IV regressions instruments with non-cyclical narrative policy indicator. Broken lines are 90%, 95% Newey and West (1987) confidence bands. Sample: Jan 1967 to Dec 2006.

Credit policy and monetary policy intertwined

We also uncover an intriguing interrelationship between GSE activities and conventional monetary policy:

- Federal Reserve interventions are important for agency credit policy. An increase in GSE portfolio mortgage purchases is accompanied by a decline in the Federal funds rate and has predictive power for narrative measures of monetary policy shocks.

- Cyclically motivated housing credit shocks accommodate contractionary monetary policy shocks. Thus, the GSEs have leaned against the wind in times of tightening conventional monetary policy.

- The transmission of agency portfolio mortgage purchases is similar to conventional monetary policy shocks transmission.

The third of these points is illustrated by Figure 3, which shows impulse responses to the same key variables following a conventional monetary policy shock, identified using the Romer and Romer (2004) estimates, compared with the impact of narrative shocks to anticipated agency purchases.2 There is little difference between the impact of the two policies on the 3-month T-bill rate, mortgage debt, and new housing starts. Housing credit policies have a more direct effect on various mortgage and housing market indicators, notably originations and real house prices. Nonetheless, a key result from this analysis is that housing credit policy operates through similar transmission channels as conventional monetary policy.

Figure 3 Responses to a shock to anticipated agency purchases versus a monetary policy shock

Notes: The figure shows responses to a one pp. increase in the expected future agency market share as well as the response to a monetary policy shock. Estimates are from local projections-IV regressions instrumenting agency commitments with the non-cyclical narrative policy indicator and instrumenting the 3-month T-Bill rate with the Romer and Romer (2004) monetary policy chock measure. Broken lines are 90%, 95% Newey and West (1987) confidence bands. Sample: Jan 1967 to Dec 2006.

The Great Depression triggered a long shadow on the US economy through the legacy of the housing GSEs. These institutions have influenced the supply of US housing credit. In this light, the Federal Reserve’s much discussed unconventional monetary policies may not be as unprecedented as usually thought, since to a considerable degree they involved the Federal Reserve taking on a role other government agencies have been carrying out since the Great Depression. Moreover, our results indicate significant interactions and similarities between these housing credit policies and conventional monetary policy, suggesting that credit policy deserves more attention in the study of monetary policy.

References

Fieldhouse, A and K Mertens (2017), “A Narrative Analysis of Mortgage Asset Purchases by Federal Agencies”, NBER Working Paper No. 23165.

Fieldhouse, A, K Mertens, and M O Ravn (2017), “The Macroeconomic Effects of Government Asset Purchases: Evidence from Postwar US Housing Credit Policy”, CEPR Discussion Paper no. 11830.

Fisher, J D M and R Peters (2010), “Using Stock Returns to Identify Government Spending Shocks”, Economic Journal 120(544): 414–436.

Leamer, E E (2007), “Housing IS the Business Cycle”, NBER Working Paper No. 13428.

Mian, A and A Sufi (2009), “The Consequences of Mortgage Credit Expansion: Evidence from the US Mortgage Default Crisis,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 124(4): 1149-1496.

Ramey, V A (2011), “Identifying Government Spending Shocks: It’s All in the Timing”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 126(1): 10–50.

Romer, C D and D H Romer (1989), “Does Monetary Policy Matter? A New Test in the Spirit of Friedman and Schwartz”, NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1989, Volume 4, pp. 121–184.

Romer, C D and D H Romer (2004), “A New Measure of Monetary Shocks: Derivation and Implications”, American Economic Review 94(4): 1055–1084.

Romer, C D and D H Romer (2010), “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes: Estimates Based on a New Measure of Fiscal Shocks”, American Economic Review 100(3): 763–801.

Endnotes

[i] We also adopt an alternative strategy identified using GSE excess stock returns, based on Fisher and Peters (2010), who use orthogonalized excess stock returns of major defense contractors to identify military spending news shocks. The main idea is that GSE profits are increasing in leverage, and thus GSE balance sheet expansions lead to idiosyncratic stock price movements. The results are very similar to our benchmark narrative approach.

[ii] The impact of the interest rate shock is scaled such that the maximum decline in the 3-month T-bill rate is identical to the purchase shock identified with the narrative instrument.