Recently, a number of studies, descriptive employment statistics, and statements by US politicians have raised concerns about the strength of US manufacturing. For example, in a January 2014 Journal of Economic Perspectives article, Martin Baily and Barry Bosworth expressed concern about the recent absolute decline in US manufacturing employment, as well as the long-recognised decreasing share of manufacturing within overall US employment. They also argued that productivity growth in manufacturing can be attributed solely to the unusual performance of computer production rather than to the accomplishments of the manufacturing sector more broadly. US Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont states on his website that “The manufacturing sector in Vermont and throughout the United States has eroded significantly in recent years and must be rebuilt to expand the middle class”. President Barack Obama has based his corporate tax reform proposals on the view that US manufacturing firms must be discouraged from “shipping jobs overseas” (State of the Union 2013).

To be sure, the evidence is indisputable that manufacturing employment has been steadily declining as a share of total US employment, and the absolute number of US manufacturing jobs has plummeted by almost 30% just since 2000.

But the perennial focus on employment masks important signs of the growing strength of the US manufacturing base. In a recent Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) policy brief (Moran and Oldenski 2014), we analyse the most detailed and up-to-date data on the state of US manufacturing.

- Our research shows that the overall size of the US industrial base – real value-added in manufacturing – has been growing rapidly for more than four decades, and is on track to surpass the all-time 2006-7 high before the end of 2014.

- In contrast to other researchers, we show that US manufacturing growth is broad-based and includes subsectors such as transportation equipment, medical equipment, machinery, semiconductors, communications equipment, and motor vehicles, as well as computers and electronics.

- Moreover, contrary to widespread hand-wringing about weakening competitive performance on the part of US firms and workers, productivity in the manufacturing sector has been growing, both absolutely and relative to other sectors of the US economy.

At the same time, the most recent data show that the productivity growth in US manufacturing is also strong in comparison to other countries.

- Finally, our research shows clearly that increased offshoring of manufacturing operations by US multinationals is associated with increases in the size and strength of their manufacturing activities in the US.

Indeed, the preponderance of net job loss in the US manufacturing sector comes within companies that stay at home and do not invest abroad. Of particular note is the large feedback to US R&D and other high-skilled services from outward investment on the part of US manufacturing multinationals.

Looking beyond employment data in US manufacturing

President Obama is the latest in a succession of political leaders who resolve that the US must find ways to strengthen the manufacturing sector and make it more competitive. Between 2000 and 2011, manufacturing jobs declined from 17.3 million to 11.6 million – a decline of 5.7 million or some 33%. There has been a slight increase in total manufacturing employment since 2010, with 12.0 million manufacturing jobs reported for 2013. This is still about a 30% decline, however, relative to 2000.

But this decline in manufacturing jobs is not because the size of the US manufacturing base is shrinking. Real value-added in manufacturing grew by 3.1% per year over the entire period 1960-2007, and after a dip during the recession recovered with 4% per year growth from 2010 through 2013. Even with a growth rate no higher than 2.8% per year, the absolute size of the US industrial base – total value-added in manufacturing – will surpass the all-time 2006-2007 high before the end of 2014.

Some authors – notably Martin Baily and Barry Bosworth (2014) – argue that this US manufacturing output growth has been driven primarily by one subsector – computers and electronics. But when we investigate the heterogeneity within the US manufacturing sector, we find that a number of other subsectors, including transportation equipment, medical equipment, machinery, semiconductors, communications equipment, and motor vehicles all grew at rates well above the manufacturing sector average.

Not only is the US manufacturing base becoming bigger than ever but the productivity of firms and workers in manufacturing leads the rest of the US economy in growing stronger. Total factor productivity and labour productivity in the manufacturing sector have been growing faster in the manufacturing sector than in the economy as a whole. At the same time, the most recent data show that the productivity growth in US manufacturing is strong not just relative to other sectors within the US, but also in comparison to other countries. In 2010 and 2011 (the most recent years for which data are available), the share of manufacturing value-added in total US GDP grew by 2.19%, while the total global share of manufacturing value-added in world income fell by 0.99%. Thus, the US is in a very strong position to compete globally in the manufacturing sector, even with sluggish employment numbers.

But major policy questions – particularly important in contemporary Washington – remain. What is the role of outward investment by US manufacturing companies in the evolution of the US industrial base? Might US firms and workers in the manufacturing sector be even larger and more competitive in the domestic economy if US manufacturing firms did less investing abroad?

The impact of offshoring by US multinationals on US domestic output, investment, and employment

To investigate the impact of outward investment by manufacturing multinationals on their operations at home, we use comprehensive firm-level data collected by the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) to empirically identify what happens when an individual firm expands its operations abroad. We employ panel regression methods with data on all US MNCs over a 20-year time period. We include firm-fixed effects that hold constant everything that is unique about a given firm, isolating how its employment in the US and the other variables we examine change when it increases its outward FDI. Thus, all the characteristics that define a given firm – such as the industry it operates in, its size, its relative market power, etc. – are controlled for and do not confound the results. We also include year-fixed effects, which hold constant everything external to the firm that was going on in a given year, thus removing any potential impact of recessions and booms.

We track the changes in employment, sales, capital investment, and R&D in the US that are associated with offshoring and other types of foreign expansion by US firms. In a novel exercise, we compare the outcomes for manufacturing multinationals strictly defined and service multinationals with manufacturing operations. This latter investigation improves upon existing studies of pure manufacturing firms. We include firms for which the majority of US operations are classified as services, including high value activities such as R&D, engineering, IT services, marketing and management, but which also offshore manufacturing production. By analysing these kinds of firms, we are able to assess how offshoring of manufacturing impacts domestic services within the same firm.

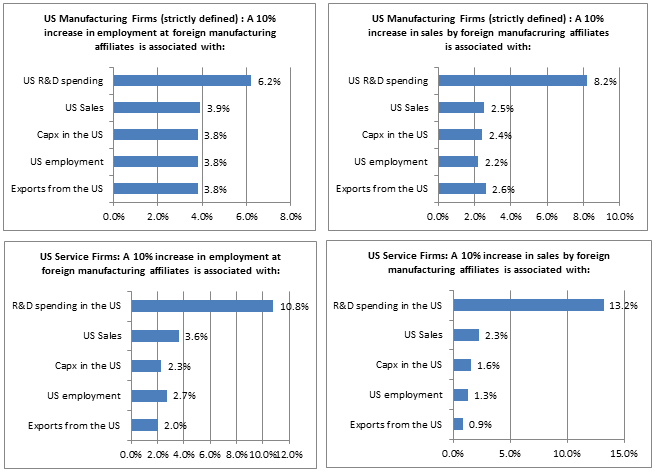

Figure 1 shows the results broken down by the primary industry of operations in the US and in the foreign affiliates of the US firms. The top panel of Figure 1 shows the results only for strictly defined manufacturing firms, that is, firms that primarily focus on manufacturing both in their US headquarters and at their foreign affiliates. The bottom panel looks at firms that primarily focus on services at their US headquarters, but that also perform manufacturing activities abroad, and shows what happens to these firms when they expand manufacturing sales or employment at their foreign affiliates.

The first thing to note about these results is that they are all positive. Thus, by any measure, expansion abroad by a US-based MNC is associated with domestic US expansion by the same firm. The foreign operations of these firms are complements to – not substitutes for – domestic US operations.

While all types of offshoring are associated with increased activity in the US, some particularly important patterns emerge.

- First, the overseas expansion of US manufacturing firms is accompanied by a positive and significant increase in employment at home.

Of course, this positive relationship does not emerge in each and every case. Some plants may close, other plants may open, and the composition of jobs within plants may change. But our results show that the creation of jobs by US multinationals abroad and the expansion of sales by US multinationals abroad are both associated with overall more jobs at home. Indeed, the preponderance of net job loss in the US manufacturing sector comes within companies that stay at home and do not invest abroad.

Figure 1. Relationship between foreign manufacturing expansion and domestic manufacturing and service activities of US MNCs

Notes: Based on regressions using BEA firm-level data from 1990-2009. All results are statistically significant at the 1% level. All specifications include firm- and year-fixed effects.

- Second, it is notable that the largest benefits from offshoring manufacturing tasks accrue to US R&D.

For example, a 10% increase in manufacturing employment at foreign affiliates of US firms is associated with a 6.2% increase in the amount of US R&D spending at the firms doing the offshoring. When the US site is primarily focused on R&D and other services, increasing manufacturing offshoring by 10% leads to a 10.8% increase in the amount of US R&D spending at that firm. When manufacturing offshoring is measured using sales by foreign affiliates, rather than employment, the increases in domestic R&D spending associated with a 10% increase abroad are 13.2% for service-focused US facilities. In other words, international expansion by US firms does not reduce their domestic activities. Instead, it is accompanied by increases in investment at home, and these increases are the largest for R&D spending.

- Finally, our results reveal that when manufacturing tasks are offshored, much of the gain for the US shows up back within the US domestic service sector.

Oldenski (2012) has shown that US MNCs offshore their relatively more routine tasks but keep the most complex and non-routine tasks in the US. This specialisation is not surprising based on the strong US comparative advantage in more highly-skilled and non-routine tasks such as innovation, engineering, and management rather than routine tasks such as basic assembly. Further work by Oldenski (2014) demonstrates that this specialisation, according to comparative advantage, results in the creation of more highly-skilled, high-wage jobs in the US.

There is no dispute that the data show that aggregate employment in the US manufacturing sector has declined since 2000. But such observed decline in domestic employment cannot be traced to the overseas expansion of US firms because of our clear confirmation that offshoring is accompanied by domestic expansion on the part of the firms that are doing the offshoring. Other factors, such as recessions, new technologies, or changes in demand must be the culprits in domestic job destruction. Quite to the contrary, if US MNCs had not undertaken the external investments and external job creation that they did during this period, the results in Figure 1 indicate that US domestic employment at US MNCs would be lower, not higher.

Conclusions

A careful look at the most recent and detailed data shows that despite falling employment, the US manufacturing base is growing larger, more productive, and more competitive. The results of our empirical analysis show that the expansion of operations abroad by US manufacturing multinationals leads to particularly strong increases in economic activity – including creation of greater numbers of high-paying manufacturing jobs – by those same firms in the US domestic economy. The policy implications are clear – any measures that the US might take to hinder or dis-incentivise outward expansion by US firms would lead to less robust economic activity – and fewer good US jobs at home, not more.

References

Baily, M N and B P Bosworth (2014), “US Manufacturing: Understanding Its Past and Its potential Future”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 28:1, 3-26.

Moran, T H and L Oldenski (2014), “The US Manufacturing Base: Four Signs of Strength”, Peterson Institute for International Economics Policy Brief Number 14-18 (June 2014).

Oldenski, L (2012), “The Task Composition of Offshoring by US Multinationals”, International Economics, Issue 131 (December).

Oldenski, L (2014), “Offshoring and the Polarization of the US Labor Market”, Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 67, May.