The UK government’s new Economy and Industrial Strategy Cabinet Committee met for the first time in August 2016. Charged with delivering ‘an economy that works for everyone, with a strong industrial strategy at its heart’, the committee is chaired by the prime minister and attended by the chancellor of the exchequer and the secretaries of state of ten other ministries.1

Concrete proposals were unveiled by the prime minister at her first regional Cabinet meeting in January 2017. The government will offer new ‘sector deals’ that will support the industries of the future where the UK has the potential to lead the world.

Deals will be organised along the lines of current collaborations with the automotive and aerospace industries, with support from the government in the form of investment in research and development (R&D), a new system of technical education and better infrastructure. The prime minister announced that the government would particularly welcome work on early sector deals in life sciences, the transition to ultra-low-emission vehicles, industrial digitalisation, the nuclear industry and the creative industries.2

UK industrial policy

People have argued about industrial strategy for a long time. Among the first economists to make a case for industrial policy was Alexander Hamilton (1791), who advocated ‘bounties’ as a way of promoting US manufacturing. In modern terms, his bounties are subsidies – and his reasoning was a precursor of the ‘infant industry’ argument. Friedrich List (1841) similarly thought that industrial growth was too important to be left to the chance of the market. Adam Smith (1776) would have disagreed.

Industrial policy is seen by some as being instrumental in the success of many East Asian economies, most notably China (Wiess 2005). The main criticism going forward is that industrial strategy may do more harm than good if the government is not well-placed to assess the costs and benefits of making deals with some sectors ahead of others.

Successful industrial policy requires the government to have the right information, capabilities and incentives to make good decisions. Pack and Saggi (2006) are worried about that being possible because “the range and depth of knowledge that policy-makers would have to master to implement a successful policy is extraordinary”. There may also be a risk that industrial policy is captured by vested interests.

Modern thinking on industrial policy has moved on since the 1960s, when it was used to create national champions in industries thought to be essential to the UK economy. These policies were generally seen as unsuccessful (Owen 2012), and past failed attempts to pick winners led Reuters to react to the launch of the Economy and Industrial Strategy Cabinet Committee by stating that “industrial policy has a toxic legacy in Britain”.3

Modern thinking in industrial policy stresses less the infant industry argument, instead arguing for intervention on the basis of knowledge spillovers, dynamic scale economies, coordination failures and informational externalities.

One of the most prominent proponents of the new thinking is Dani Rodrik (2004). He sees long-term growth as depending on the development of fundamental capabilities in the form of human capital and institutions, and so argues that “the right model for industrial policy is not that of an autonomous government applying Pigovian taxes or subsidies, but of strategic collaboration between the private sector and the government with the aim of uncovering where the most significant obstacles to restructuring lie and what type of interventions are most likely to remove them”.

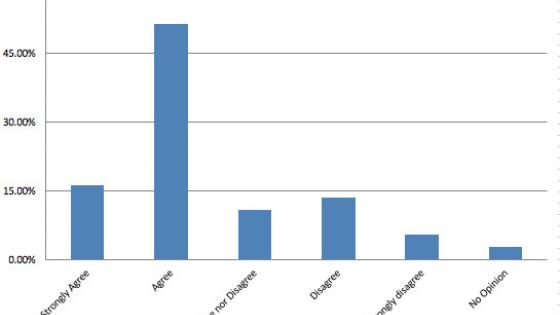

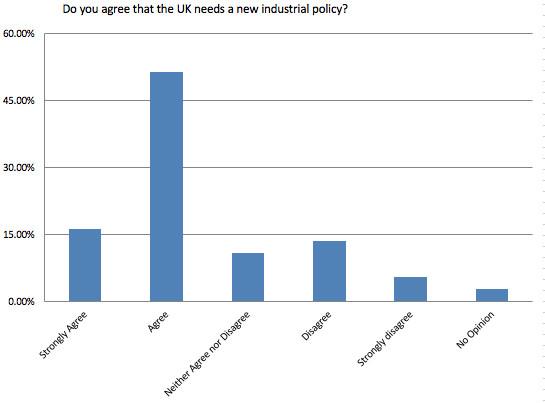

Q1: Do you agree that the UK needs a new industrial policy?

A majority of UK-based macroeconomists agree that the UK needs a new industrial strategy, although many doubt that the government is well-placed to deliver good policy. Of the 36 economists who answered this question in the Centre for Macroeconomics (CFM) survey, 25 (69%) agree or strongly agree that the UK needs a new industrial policy. Seven (19%) respondents either disagree or strongly disagree, with four (11%) neither agreeing nor disagreeing. When weighted by self-reported confidence in their opinions, the proportion agreeing that the UK needs a new industrial strategy is 72%.

There is widespread agreement among those surveyed that the debate over industrial policy takes place against a backdrop of years, if not decades, of weak productivity in the UK.

There is also universal disappointment at experiences with previous UK industrial policies from the 1950s to the 1970s. As David Miles (Imperial College) puts it, “the UK has a woeful history of government initiatives on industrial policy”. Richard Portes is similarly damning when asking rhetorically “which of our successful firms have benefitted from ‘industrial policy’?” Michael Wickens (Cardiff Business School) thinks that “in the past, in the UK, it has proved a waste of money”.

The distinction between good and bad industrial policy is recognised by almost all respondents, irrespective of whether they agree or not that the UK needs a new industrial strategy. Good policy, as favoured by Nicholas Oulton (London School of Economics, LSE), requires “additional spending by the state on infrastructure, R&D, training, and education, since it is well known that we have clear deficiencies in these areas”.

The need to direct industrial policy towards raising UK capabilities is a recurring theme in respondents’ comments. Examples of bad policy would be the ‘picking of winners’, which Jagjit Chadha (National Institute of Economic and Social Research, NIESR) worries “may freeze the economic structure and distort incentives”; or measures aimed at “preserving jobs in established industries”, which Christopher Pissarides (LSE) would not support.

David Bell (University of Stirling) thinks that “any new policy should avoid focusing on individual companies”. How the government’s proposals relate to good and bad policy exercises Patrick Minford (Cardiff Business School), who thinks that “the part of the policy that invites ridicule is the “backing of winning sectors and industries”, but I doubt whether this will gain traction.”

What divides panellists most is whether the government is likely to introduce good or bad policies. All those who disagree with the call for a new UK industrial strategy base their opposition in part on a belief that industrial strategy is more likely to involve bad than good policies.

Morten Ravn (University College London, UCL) says “it is hard to believe that policy-makers are in a strong position to apply an efficient industrial policy, free of concerns about voters and current financial interests, and given how strongly parties with vested interests will try to impact on the policies.” Arguing similarly that no policy may be better than bad policy, Tony Yates (University of Birmingham) “would prefer limited state capacity and resources to be directed towards providing public goods better and more efficiently.”

UK regional policy

The Economy and Industrial Strategy Cabinet Committee has not explicitly pronounced on the regional implications of using industrial policy to promote new sector deals. Many countries have adopted several different flavours of regional policy.

An existing UK government policy that targets regional concerns is the Enterprise Zones programme, which was last expanded in the 2015 Spring Budget.4 In common with similar initiatives around the globe, the aim is to promote development in specific locations through tax concessions, infrastructure incentives and reduced regulation. Across England, 48 Enterprise Zones are planned to be in place in 2017, specialising in a wide range of business sectors. Businesses in Enterprise Zones benefit from 100% business rate discounts, simplified planning procedures, government support for superfast broadband, and enhanced capital allowances.5

The performance of UK Enterprise Zones was evaluated by the Department of the Environment in 1995 (PA Cambridge Economic Consultants 1995). That study concludes that around 126,000 jobs were created since the 1980s, of which up to 58,000 were additional jobs. The cost per additional job created was around £17,000 (£26,000 at 2016 prices), based on an assumed ten-year job life.

More recently, research by Criscuolo et al. (2016) finds that areas in the UK eligible for Regional Selective Assistance created significantly more jobs than ineligible areas. This treatment effect was driven by the behaviour of small firms, and was not due to job displacement between eligible and ineligible areas.

In the US, Rubin and Wilder (1989) conclude that the Urban Enterprise Zone in Evansville, Indiana, was cost-effective in creating jobs and so “can be a cost-effective local economic development tool.” In 1996, the same authors surveyed 34 state programmes, concluding that enterprise zones “have not lived up to the broad panacea-like imagery conjured up by early Federal proposals”, but still maintain potential utility as an economic development tool (Rubin and Wilder 1996).

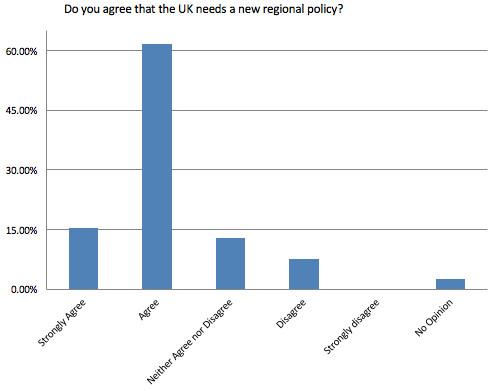

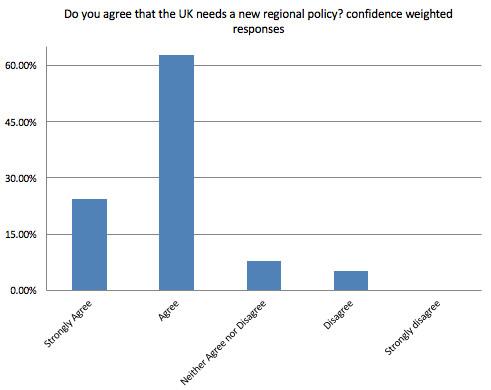

Q2: Do you agree that the UK needs a new regional policy?

An even larger majority of UK-based macroeconomists agree that the UK needs a new regional strategy. Of the 38 panellists who answered this question in the CFM survey, 30 (79%) agree or strongly agree that a new regional strategy is needed. Only three (8%) respondents disagree with the proposition, with five (13%) neither agreeing nor disagreeing. The proportion agreeing on the need for a new UK regional strategy rises to 87% when responses are weighted by self-reported confidence levels.

Many panellists are concerned about regional inequality in the UK. Wouter Den Haan (LSE) notes that “UK regional developments have been very skewed with unequal progress across the country”, and Angus Armstrong (NIESR) supports a new regional policy “for many reasons, not least the legitimacy of our external policy and the integrity of the union.” Panicos Demetriades (University of Leicester) argues that Brexit makes the need for regional policy even more pressing, because “the less-favoured areas in the UK that benefitted from EU structural funds will suffer otherwise, and that will increase regional disparities.”

Several respondents would like to see regional policy focused on cities. Wendy Carlin (UCL) believes that “the focus should be on productivity policy for cities and on understanding the difference between dynamic cities and those that are left behind.” John Van Reenen (MIT and LSE) says that “the UK needs to continue to decentralise more power to city-regions.” And Ray Barrell (Brunel University) is even more specific in wanting regional policy to “encourage potential growth poles such as Oxford, Cambridge, Edinburgh and Manchester, based around world class universities.” The success of such policies in France is noted by Nicholas Oulton.

As with industrial policy, opposition to a UK regional strategy among survey respondents is based on fears that new policy will be poorly implemented by the government. Ethan Ilzetzki (LSE) says that “I can see some rationale for regional policy, but again am not sure this is helpful in practice.” The other sceptics are David Miles (Imperial College), who is “doubtful that a ‘new regional policy’ will be very successful”, and Patrick Minford (Cardiff Business School), who is concerned that promoting regional growth “involves politicians making judgements about the economy’s structure for which they have no basis.”

Even though he agrees that the UK needs a new regional policy, David Smith (Sunday Times) warns that “reversing decades of relative decline for some of Britain’s regions will itself take decades.”

References

Criscuolo, C, R Martin, H Overman and J Van Reenen (2016), “The Causal Effects of an Industrial Policy”, DEP Discussion Paper No. 1113

Hamilton, A (1791), Report on the Subject of Manufactures.

List, F (1841), The National System of Political Economy.

Owen, G (2012), “Industrial policy in Europe since the Second World War: what has been learnt?”, Occasional Paper No. 1, European Centre for International Political Economy.

PA Cambridge Economic Consultants (1995), Final Evaluation of Enterprise Zones, HMSO.

Rodrik, D (2004), “Industrial Policy for the Twenty-First Century”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 4767

Rubin, B and M Wilder (1989), “Urban Enterprise Zones: Employment Impacts and Fiscal Incentives”, Journal of the American Planning Association 55(4).

Rubin, B and M Wilder (1996), “Rhetoric versus Reality: A Review of Studies on State Enterprise Zone Programs”, Journal of the American Planning Association 62(4).

Smith, A (1776), An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations.

Weiss, J (2005), “Export Growth and Industrial Policy: Lessons from the East Asian Miracle”, Asian Development Bank Research Paper No. 26

Endnotes

[1] “New Cabinet committee to tackle top government economic priority”, Government Press Release, 2 August 2016, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-cabinet-committee-to-tackle-top-government-economic-priority

[2] “PM unveils plans for a modern Industrial Strategy fit for Global Britain”, Government Press Release, 22 January 2017, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pm-unveils-plans-for-a-modern-industrial-strategy-fit-for-global-britain

[3] “PM May resurrects industrial policy as Britain prepares for Brexit”, Reuters, 2 August 2016, http://uk.reuters.com/article/us-britain-eu-industry-idUKKCN10C3CR

[4] Enterprise Zones, House of Commons Library Briefing Paper No. 5942, 17 March 2016

[5] HM Government, http://enterprisezones.communities.gov.uk/