The currency options of an independent Scotland have become a crucial point of contention for both sides ahead of the September 2014 referendum. However, the debate has so far focused on the suitability of different regimes based on the optimal currency area framework or fiscal implications (Armstrong 2013). There has been little focus on the practical issues involved. This is problematic because a breakup of the sterling area would be historically unprecedented and uniquely complex.

No precedents for a sterling area breakup

First, most recent currency area breakups (or discussions around breakups!) have been of federal systems. In federal systems, national central banks or quasi central banks provide liquidity to their banking sectors and are connected by a common payments system. To break up such an arrangement, one of the participants bilaterally or unilaterally terminates their commitment to keep central bank monies equivalent, and deposits in their respective banks are de facto redenominated. To take the Eurozone as an example, a Greek exit would have involved the Bank of Greece being cut off from the ECB Target 2 payments system. But the UK’s monetary arrangements are unitary in nature. All banks clear with the Bank of England through an indivisible payments system. Splitting up the currency union would require cleaving individual banks from their settlement accounts with the Bank of England.

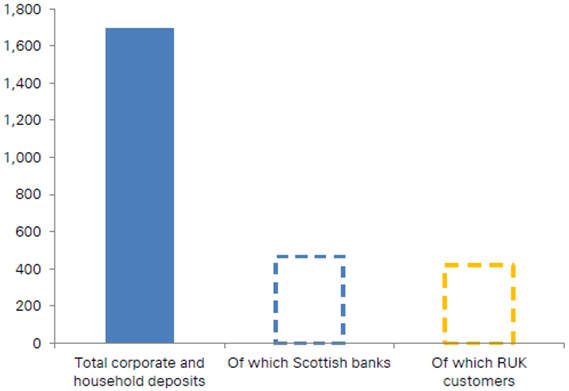

The second feature that makes the sterling union unique is that the UK’s financial system is tightly integrated and highly complex. In contrast to the Eurozone where, for example, the business of Greek banks is mostly concentrated in Greece, Scottish banks do the overwhelming majority of their business over the border in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Moreover, these banks are systemically important to the whole of the UK’s banking system. Our analysis suggests that Scottish banks make up around 25% of the UK’s deposit base.1 In addition, bank assets are large and complex, principally as a result of the investment banking activities of RBS.

Figure 1. Split of UK deposit base in Scottish banks

Source: Deutsche Bank, own estimates based on balance sheets of RBS, Bank of Scotland, Clydesdale, HM Treasury Analysis and UK National Balance Sheet, ONS.

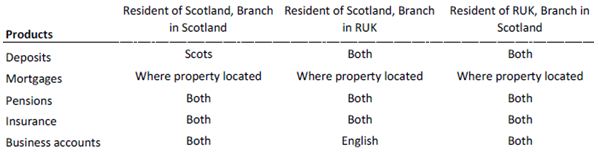

The third difference with other currency areas is that the UK has two overlapping legal systems. The principal of lex monetae is well established when it comes to redenomination exercises in the wake of breakups of currency areas or pegs (Allen & Overy 2012). However, this principal is based on states redenominating contracts governed by their sovereign law. While Scotland does have its own body of law (Scots law), there has been no consistent approach as to when Scots law or English law has been chosen as the applicable law of contracts. Indeed, in the case of retail contracts the governing law can be a function of the residence of the counterparty, in other cases the branch, and in others the headquarters of the bank itself.2

Figure 2. Scots and English law overlap in governing financial contracts in Scotland

What are the policy implications?

The first is that unilateral exit from the sterling area is impossible. The continuing UK could not ‘kick’ Scotland out of the currency area because to do so would involve cutting off Scottish banks from Bank of England liquidity. Unlike Germany cutting Greece off from the ECB, this would in the process redenominate the deposits of all who are customers of Scottish banks, including those that remain in the continuing UK. It would also remove a lender of last resort for Scottish banks. No lender of last resort is only desirable in banking systems when the costs of liquidating banks are small (Gale and Vives 2002), or when banks hold large quantities of net external assets – such as in the case of Ireland following currency breakup (Ó Gráda 1995), or Hong Kong currently. Neither is true of Scottish banks.

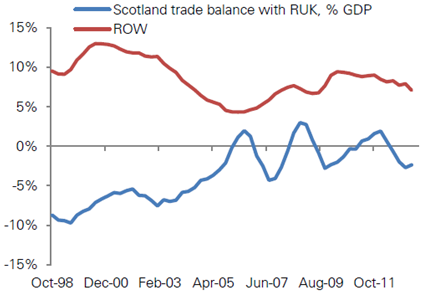

On the other hand, it would be close to impossible for a Scottish government to unilaterally ‘share’ sterling with the continuing UK without central bank financing (sterlingisation). Sterlingisation would mean importing hard currency through surpluses on Scotland’s balance of payments. However, using experimental national accounts data from the Scottish government, our analysis suggests that Scotland already runs a bilateral current account deficit with the continuing UK. This means Scotland would be forced to finance itself through loans from London. Moreover, this deficit would itself be highly sensitive to oil prices. If these fell, financing from London could dry up. To prevent running out of hard cash, Scotland would have to undergo internal adjustment. The recent Eurozone crisis shows quite how expensive internal adjustment can be in output terms.

Figure 3. Scotland runs a bilateral trade deficit with the continuing UK

Source: Deutsche Bank, Scottish National Accounts Project.

One option for policymakers is to work together to separate banks headquartered in Scotland and transition to a new Scottish currency. Past currency redenomination exercises – such as that of Argentina – suggest that piecemeal redenomination can cause substantial costs, meaning that it would be wise to simultaneously redenominate the assets and liabilities of Scottish banks. However, this process needs to be done quickly and efficiently. Currency crises have a habit of becoming self-fulfilling (Krugman 1996) and a key catalyst can be expectations of redenomination risk (Levy-Yeyati et al. 2010). In Scotland’s case, such an exercise would be impossible without substantial pre-planning. Indeed, even in currency areas with separated banking systems, preparation has been taken long in advance (Dědek 1996). Distinguishing between banking assets and liabilities is made all the more complex in Scotland’s case by the country’s overlapping financial and legal systems. If the Westminster government were to maintain its position after a ‘yes’ vote in September that a currency union with Scotland would be impossible, plans would be have to drawn up now, rather than after the referendum, as expectations of redenomination risk would immediately arise, leading to capital flight from Scotland to the rest of the UK.

A final option for the hypothetical future Scottish and continuing UK governments would be a currency union. This would be the least complex and risky option. However, such an arrangement would likely be suboptimal for both sides. In the long run, successful currency areas are the result of high levels of business cycle correlation during shocks (Mundell 1968). Scotland and the rest of the UK currently have highly correlated business cycles compared, for example, to Greece and Germany. However, over time these correlations could weaken – particularly as Scotland’s economy becomes more dependent on oil. It is easy to envisage a situation in which the diverging economic priorities of both governments question the credibility of the currency area. Some kind of fiscal and banking union would be required to backstop the currency area, as would a series of rules to ensure that the economic policies of both policies were well aligned. However, the Eurozone crisis shows that these frameworks are easily broken and can lead to suboptimal outcomes.

Conclusion

A practical analysis of an independent Scotland’s currency options shows that a unilateral breakup, by either side, would be close to impossible because of the costs to financial stability. Even a mutual exit would be extremely complicated and risky, and would require policymakers to be planning already. A currency area would thus be the only viable option in the short term. However, as the Eurozone demonstrates, if badly designed this can be an exceptionally costly outcome.

References

Armstrong, Angus and Monique Ebell (2014), “Scotland: Currency Options and Public Debt”, National Institute of Economic and Social Research, March.

Allen & Overy (2012), “The euro: the ultimate crib”, A&O Global Law Intelligence Unit, July.

Dědek, Oldřich (1996), The Break-up of Czechoslovakia: An In-depth Economic Analysis, Aldershot: Avebury.

Frankel, Jeffrey (1999), “No Single Currency Regime is Right for All Countries or at All Times”, NBER Working Paper 7338, September.

Gale, Douglas and Xavier Vives (2002), “Dollarization, Bailouts, and the Stability of the Banking System”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(2), May.

Harvey, Oliver (2014), “Should auld acquaintance be forgot? Your guide to a new Scottish currency”, Deutsche Bank Research Report, May.

Krugman, Paul (1996), “Are Currency Crises Self-Fulfilling?”, in Ben S Bernanke and Julio J Rotemberg (eds.), NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1996, Volume 11, January.

Levy-Yeyati, Eduardo, María Soledad Martínez Pería, and Sergio L Schmukler (2010), “Depositor Behavior under Macroeconomic Risk: Evidence from Bank Runs in Emerging Economies”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 42(4), June.

Mundell, Robert (1968), “A Theory of Optimum Currency Areas”, Chapter 12 in International Economics, New York: Macmillan: 177–186.

Odling-Smee, John and Gonzalo Pastor (2001), “The IMF and the Ruble Area, 1991–93”, IMF Working Paper, August.

Ó Gráda, Cormac (1995), “Money and banking in the Irish Free State 1922–1939”, in Charles H Feinstein, Banking, currency and finance in Europe between the wars, Oxford: Clarendon.

1 Calculated using HM Treasury analysis and banks’ balance sheets.

2 As illustrated by the terms and conditions of retail products issued by UK banks.